Le Coucher de Sappho by Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre

I have been besotted with the ancient Greeks of late, working my way through the magisterial The Greeks and Greek Love: A Bold New Exploration of the Ancient World, by James Davidson. The book is almost 800 pages long, in small type, so it’s a long haul. But I have had more fun with this book than any book I’ve read in months. Davidson is an Oxford-trained historian, but he writes with wit and humor. His approach is anything but dry. And rather than merely throwing out his analysis with a haughty academic attitude of take it or leave it, Davidson takes us into the texts. He lets us see for ourselves the basis of his interpretation of Greek history. We meet hundreds of characters from all over the Greek empire. He retells hundreds of stories from classical Greece. By the end of the book, you feel as though you’ve been on vacation in ancient Greece, and you’ve picked up a surprising amount of Greek vocabulary.

Thanks to Davidson, I also have discovered the poetry of Sappho. Right away I saw that she was the Greek Edna St. Vincent Millay. Here’s a fragment, translation by A.E. Housman:

The weeping Pleiads wester,

And the moon is under seas;

From bourn to bourn of midnight

Far sighs the rainy breeze:

It sighs from a lost country

To a land I have not known;

The weeping Pleiads wester,

And I lie down alone.The rainy Pleiads wester,

Orion plunges prone;

The stroke of midnight ceases,

And I lie down alone.

The rainy Pleiads wester

And seek beyond the sea

The head that I shall dream of,

And ’twill not dream of me.

What is sad is that very little of Sappho’s poetry remains. She was born around 600 B.C., but most of her work survived until Roman times. Then Sappho’s work was at the mercy of the Christians. It seems there were book-burnings. The church was redefining love according to its own brutally prudish theology, so these ancient ideas had to go. But it was not only an active purging of the literary record by the church. It also was neglect of those documents that survived and found their way into monastery libraries during the Dark Ages. Davidson tells us how this neglect probably happened:

“Time and again, a manuscript of Sappho’s songs or of Strabo or of Archimedes, one of only two or three copies in the world, or one of only one, was allowed to rot in the book box, while the scribe spent his precious hours making yet another copy of the painfully awful Greek prose of the evangelists. Or worse, the priceless thousand-year-old text was systematically erased and overwritten to make a private copy of the more polished pieties of some bestselling Christian sermonizer.”

It’s a pity that the sermons weren’t burned instead.

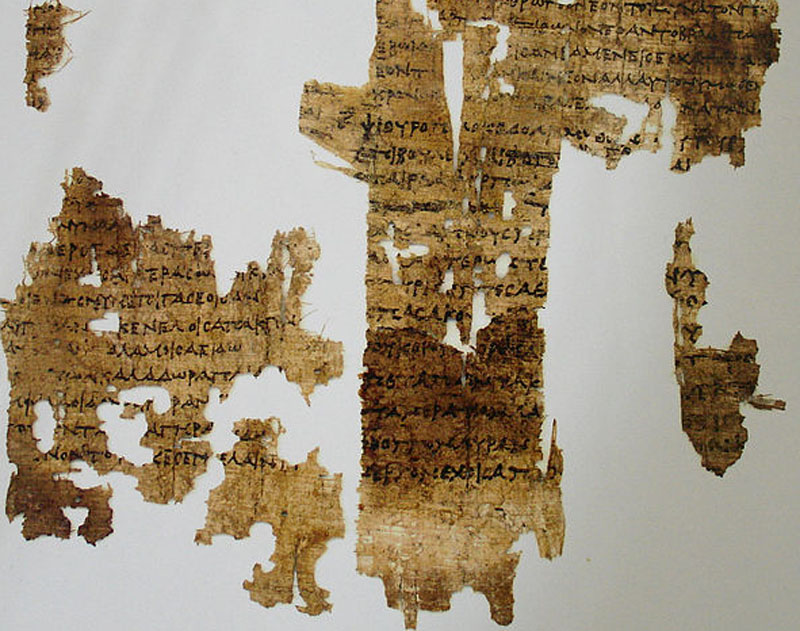

Fragments of a Sappho poem discovered and published in the 20th Century

One Comment

Beautiful poetry. Seems almost a miracle that any of her works survived at all. I enjoy your blogs and especially your command of language.

Post a Comment