Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity. John H. Holland. Addison-Wesley, 1995. 176 pages.

This is not a book review. Rather, this is about why I think the ideas in this book are important, and how those ideas apply to what we think and what we do. This is one of the most important books I’ve ever read, so it’s surprising that I’ve never mentioned it here before. That’s probably because it was more than 25 years ago that I first read it. The author is, or was, a professor of computer science, electrical engineering, and psychology at the University of Michigan.

The book is rather technical, but its central ideas are easy to grasp. There are several key concepts:

Complex adaptive systems: We are entirely familiar with complex adaptive systems, because we are surrounded by them. A city is a complex adaptive system, as is a forest, or any ecosystem. In fact each individual human being is a complex adaptive system.

Adaptive agents: An agent is a smaller entity within a complex adaptive system that is able to act on its own. It’s also able to learn. And, as a species, it is able to evolve based on interaction with the environment. For example, an individual human being is an agent within the complex adaptive system of human society. A tree, or a squirrel, or a mouse, is an individual agent within a forest. Each, as a species, evolves.

Tags: Tags are attributes that allow agents to identify other agents or other elements within a system. A human being can recognize a squirrel, or a grizzly bear, because our vision detects the visual tags that denote squirrels and grizzly bears. A squirrel can detect a nearby nut by the nut’s smell. Everything within a system will have some sort of tag, permitting agents to recognize what a thing is or even to register that something new and unfamiliar has been encountered. A flower’s bright color, and its scent, are tags that other agents (bees, hummingbirds) can recognize.

Internal models: Agents will always have some sort of internal model of their environment. A mouse’s internal model will understand that a certain smell is a tag that identifies a mushroom as food. A mouse’s internal model also will understand that other smells are a tag for a predator, and the mouse will hide. Internal models vary in their complexity, according to the abilities of the agent. A human being’s internal model of the environment is more complex than an amoeba’s. Internal models, to a great degree, are inherited as instincts. Yet inherited instincts can become obsolete and dangerous if the environment is changing faster than a species can evolve. But internal models also can learn, including the ability to detect and correct errors, if the agent survives the error. Some agents’ internal models are better than other agents’ internal models. Some human beings, obviously, learn faster than others. Some human beings recognize errors more quickly than others.

Competition: Agents have no choice but to compete with other agents for resources within a complex adaptive system — food, mates, social status, power.

Now we can propose an axiom. The quality of an agent’s adaptation to its environment is only as good as its internal model of that environment. A young squirrel that hasn’t yet learned that roads are dangerous is at risk of dying on a road. Young millennials who perceive the growing role of computers in their environment and who have learned to program computers will get a better job than working in a warehouse. A decision, or an action, is only as good as the factual basis and reasoning that went into that decision or action.

All of this has to do with an area of science which is developing very quickly, a science that can be applied to a great many things — say, to studying the ecology of an ocean, or to programming a computer system for artificial intelligence. My interest though, is pretty specific and limited: What does the science of complex adaptive systems tell us about the quality of our adaptation, as individual human beings, to living in a fast-changing world? How can we use the theory to improve our adaptation and therefore to improve our lives, not only as individuals but as a society? How might the theory help us understand not only the poor performance of some people, but also the destructive tendencies of people whose models of the world are false and twisted? (In human beings, values also are a part of the internal model. I’ve written here in the past about the inferiority of conservative values. The conservative love of authority obviously is a invitation for error, whereas the liberal’s love of fairness is not likely to go wrong.)

Our environment surrounds us with dangers as well as with potential rewards. And we must compete whether we like it or not.

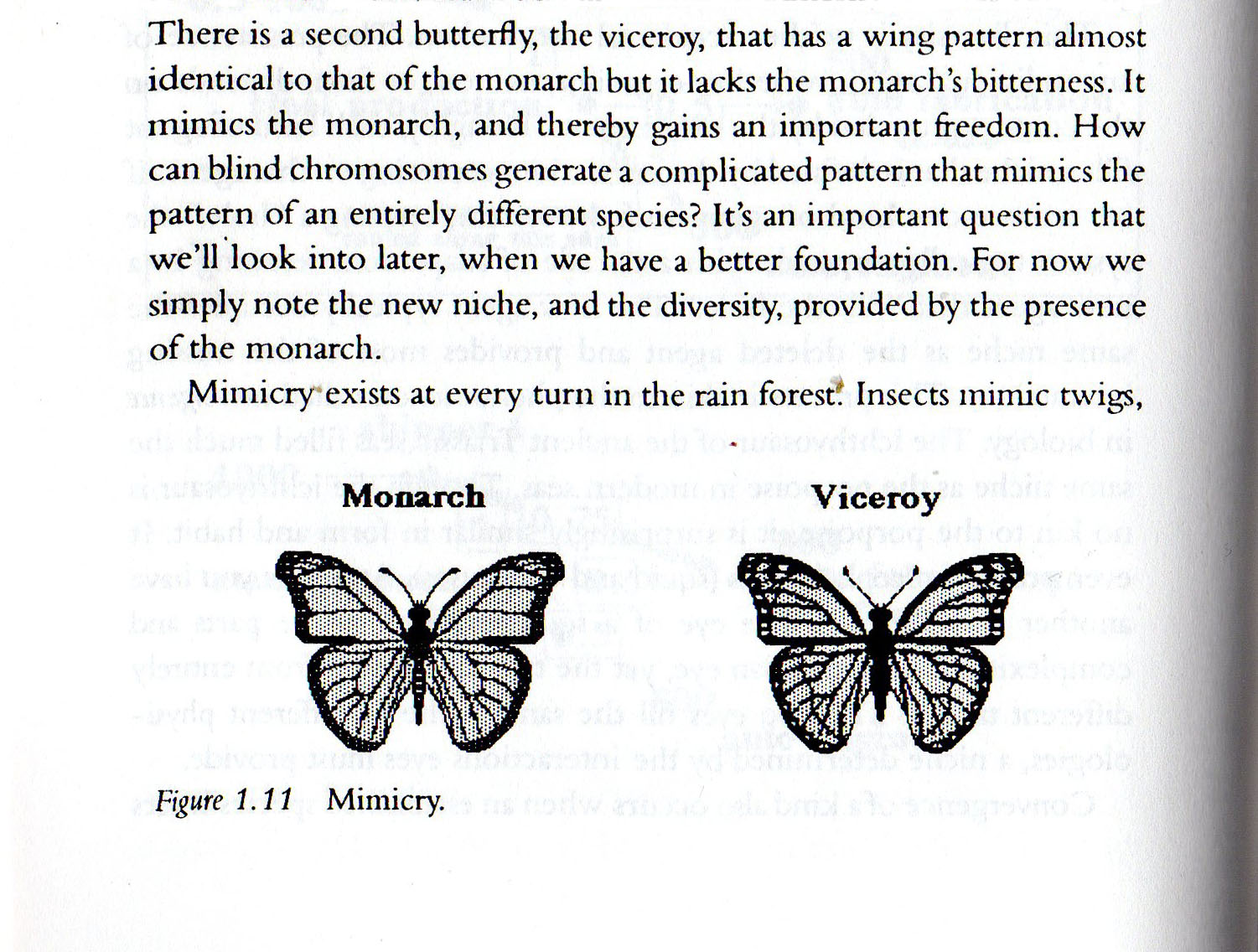

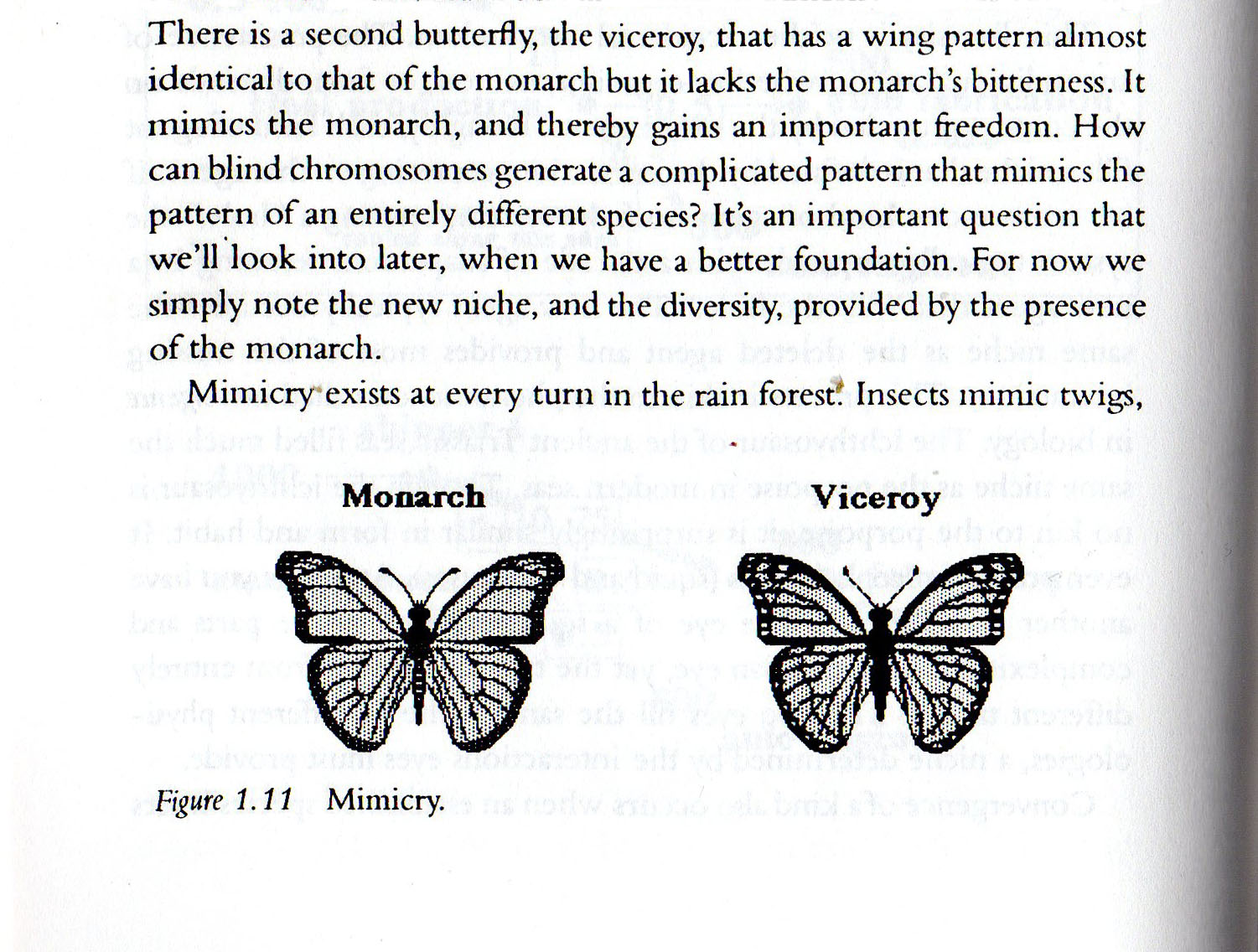

Some agents lie. They lie to exert their own interests against the interests of other agents. For example, mimicry in the animal kingdom:

To a bird, viceroy butterflies are good to eat. But a monarch butterfly will make them throw up. The butterflies look alike. Birds’ internal models learn that monarch butterflies are bad to eat, and so they don’t eat viceroys either.

Now you see where I’m going with this. Millions of human beings are operating with severely defective internal models of the world. For some it’s because they’ve been lied to. That’s the very purpose of propaganda, after all. For others, it’s sadly because they’re just not swift enough to make sense of a fast-changing environment that makes them feel threatened. They get left behind. Believing lies told by others, they get used for others’ purposes.

But there is no avoiding the bottom line. Those whose internal models of the world are defective, or too slow to keep up, will do badly in the world. Those whose internal models are more accurate and more up to date will do better in the world. When groups of people with defective models of the world act in concert, they are certain to do harm. When those with more accurate models of the world operate in concert, they have a good chance of doing good.

Those of us who have pretty good, or at least adequate, internal models of the world (I don’t hesitate to make that claim for myself) have been living through a period in which people with false models of the world temporarily got the upper hand, through the concerted application of lies and deception. As angry as I once was when Trump first acquired power through the support of those whose models were weak and corruptible, I was more optimistic than many people that, before long, the movement would fail. That optimism derives from the simple proposition that people, and groups of people, with corrupted models of the world are bound to fail, at least eventually, because their corrupt model of the world will cause them to make errors, errors that will build up until those errors become fatal and bring them down, as surely as a young squirrel in the road that hasn’t learned about cars. Now, at last, the failures and errors of Trump world are taking down those who thought that lies and the abuse of others was a winning strategy. Had they known their history, they would have known that that model has been tried before, and that it caused great misery for many before its sponsors were exposed and eliminated. Think of Stuart Rhodes, or Alex Jones, or Steve Bannon, all of whom were major sponsors of a false model of the world meant to cause susceptible people to be conned, fleeced, and manipulated. Rhodes, Jones, and Bannon are now being exposed and eliminated as dangerous agents in the environment. The same fate awaits Donald Trump.

It greatly disturbs me that there are so many forces that actively work to corrupt people’s model of the world — Fox News, the Republican Party, billionaire oligarchs, con men. That’s possible because so many people’s model of the world is faulty and therefore vulnerable to being corrupted. Their lie detectors, so to speak, are broken. They fall for scams. They allow themselves to be used, en masse, for other people’s purposes. They don’t learn. They don’t correct errors. He’s still my president.

This begs the question: What are the things that support accurate internal models of the world? How do we avoid the invitations to deception and falseness that are constantly set before us? I don’t have an easy answer to that, and I’ve already gone on here for too long. But a few things are quickly apparent. Education matters. Reason matters, as in the ability to detect fallacy and therefore the ability to detect attempts to deceive us. Some means of sorting out truth from falsehood, in the way courts work, or in the way responsible journalists work, is essential. Some kind of principle of skepticism and caution must be applied when we recognize that we are obliged to act but don’t have enough information. So-called “faith” is one of the most common traps of all. There must be some mechanism for detecting and correcting errors. And, if those with good models of the world want to make the world better, then there must be a means of comparing notes with others and acting in concert with others.

An aside: Back in the 1960s and 1970s, Carlos Castaneda wrote some beautiful books that were supposedly about a Mexican shaman named Don Juan. He sold more than 8 million books. But later it was proven that Castaneda was doing not anthropology but fiction (though good fiction!). The Don Juan character has a well developed theory of what he called “petty tyrants.” We all know petty tyrants. Workplaces are full of petty tyrants. They’re the people who make a little power go a long way and who bring conflict and misery to everyone around them. Don Juan’s theory was about how to take down a petty tyrant. The key was to wait, on the grounds that sooner or later, every petty tyrant makes a fatal mistake, at which point a flick of the finger will take them down. In my working life, I always found that to be true. The petty tyrants who afflict other people and bend the rules eventually go down, vulnerable to their own errors. They make a mistake that requires the HR department or higher management to send them packing.

A good example is James Bennet, who resigned as opinion editor at the New York Times after he made a fatal mistake, which was publishing a piece of right-wing propaganda that the Times should not have published. Bennet’s friends complained that a group of young “woke” staff members at the Times “canceled” Bennet. He certainly wasn’t canceled, because he landed on his feet at the Economist. My suspicions tend otherwise. I’d wager that Bennet was an incompetent, overbearing editor who was hated by his staff. When the staff, with better internal models of the world than Bennet’s, recognized Bennet’s fatal mistake, they made their move. The full story, I would wager, was that Bennet deserved to be fired long before he made his fatal mistake. As for the piece Bennet published, which the publisher of the Times called “a significant breakdown,” Bennet’s approval of the piece was sufficient evidence of his incompetence and his defective internal model of the world.