Click on image for larger version

Have we had a music post lately? I thought not. Get out your headphones and your thinking cap, and let’s talk a bit about fugues.

It’s no secret that I’m obsessed with fugues. Everyone with a nerdly approach to music is obsessed with fugues. Recently I recommended to a friend who is taking up music that he explore this Yale online course on listening to music:

Notice that the instructor devotes an entire lecture, lecture 13, to fugue form. In the lecture, he says that every educated person should understand fugues. Yes!

I have never been anywhere close to having the technique required for professional musicians. I had a private organ teacher through junior high school and high school, and later, as an adult, I worked on my piano technique in the community music program of the University of North Carolina School of the Arts. During those times when I have practiced conscientiously, I’d put myself in the category of “accomplished amateur.” That is nothing to be ashamed of. So often, people who are quite good musicians but who are not professional material feel a kind of shame, because they know enough to compare themselves with professionals. It ought not to be that way. All of us ought to be able to make our own music and share it with friends in the same way that we ought to be able to make our own supper and share it with friends.

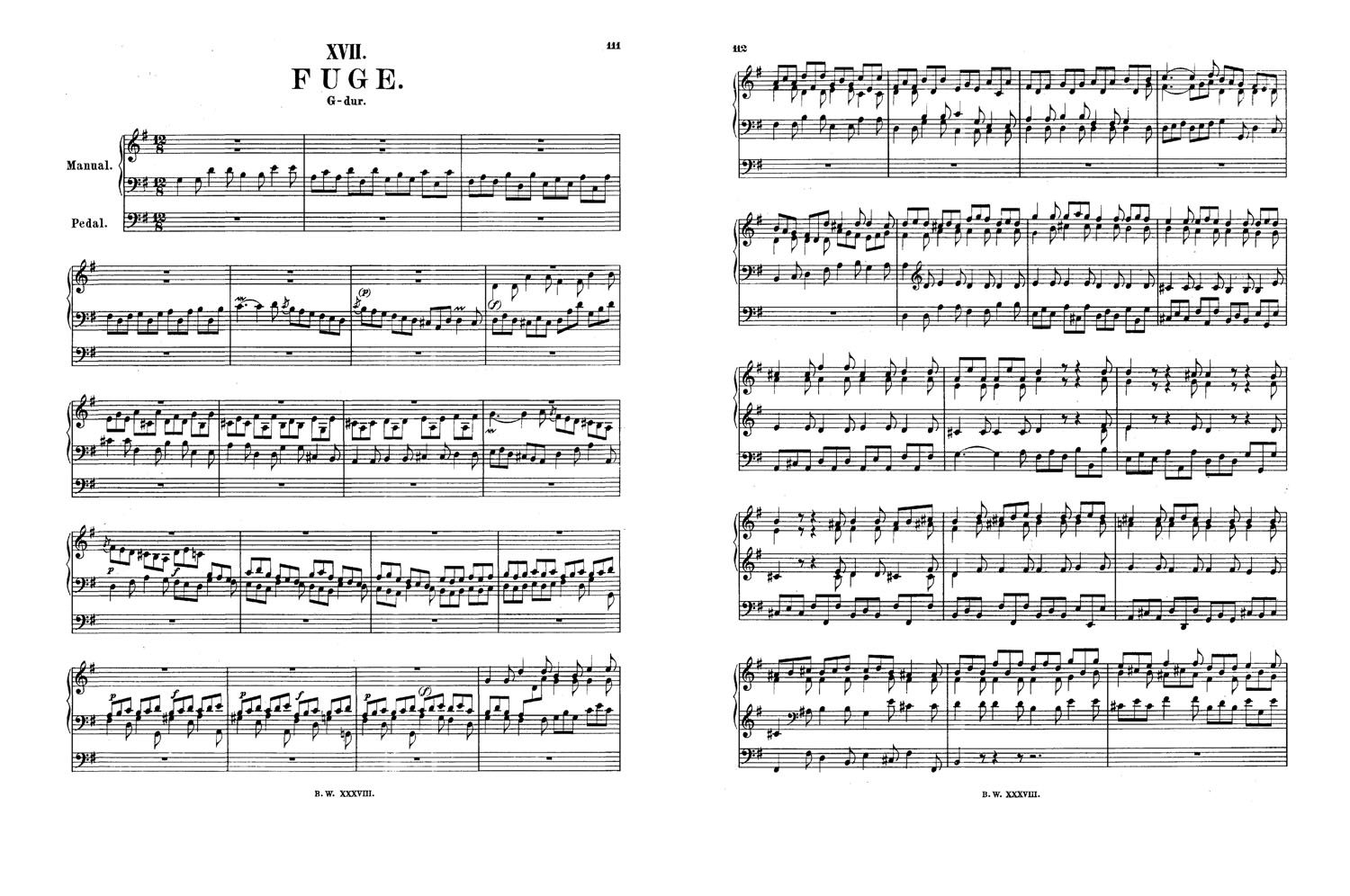

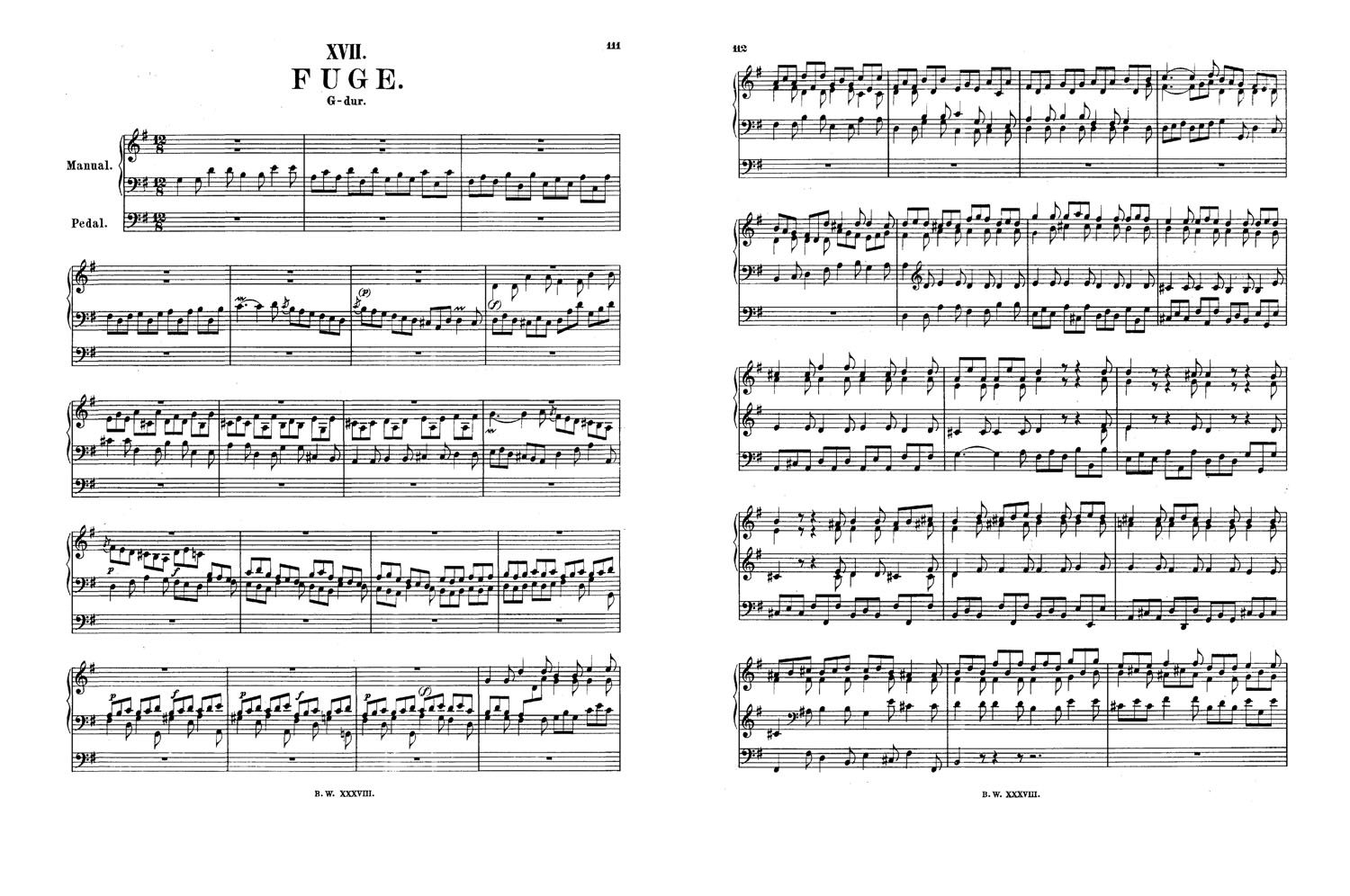

Anyway, fugues. The top photo shows the first two pages of J.S. Bach’s Fugue in G major for organ, BWV 577. What does the “BWV” mean? It stands for Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis, German for Bach Works Catalog. It’s the system used for specifically identifying all of Bach’s compositions. The BWV 577 fugue is often called the “gigue” fugue, generally pronounced “jig” by English speakers. Why it’s called the jig fugue is pretty obvious. It sounds like a wild country dance.

An important thing to know about fugues is that fugue form is a contrapuntal form. “Contrapuntal” is just a Latinate form of the English word “counterpoint.” In counterpoint, the composition is made up of independent lines, or voices. Each line or voice, heard alone, is much like a complete melody itself. Heard together, the voices blend harmonically and rhythmically into a complex whole.

How should you listen to counterpoint? Unless you concentrate very carefully on following each separate voice, you will hear only the whole. The challenge — and the challenge has everything to do with why nerds love fugues — is to concentrate so intensely that your ear can follow each voice separately and hear the independent voices inside the whole.

A convenient thing about fugue form is that the voices usually enter the composition one at a time. The first voice starts alone (usually but not necessarily the highest voice) and states the main theme of the fugue. And then while the first voice gets involved in a variation on the main theme of the fugue, the second voice comes in. The second voice states the main theme again. Then while voices one and two wind around together and get even more deeply involved in variations on the theme, the third voice comes in and states the main theme of the fugue. And finally the fourth voice. Again and again as the fugue progresses, you’ll hear the main theme repeated, along with many variations and inversions of the main theme.

Part of what makes the BWV 577 organ fugue a good study case is that the main theme of the fugue is incredibly appealing and infectious. You’ll recognize it every time it repeats.

Got your earphones? Let’s listen to three different performances of the BWV 577 fugue. The differences in the performances are very telling. The first performance is by Simon Preston. Preston is organist at Westminster. I’m not the only person who regards Preston as the best living organist, especially for Bach. Preston aims for a clean and highly articulated style of playing. He doesn’t try to dazzle you with how big the organ can sound. Rather, he plays in a way that maximizes the chances that you will actually be able to follow all the voices of the fugue. His recordings are often made on “baroque” style instruments that recreate the type of organs that existed in Bach’s day. Preston doesn’t pull out a lot of stops and make a lot of noise. He uses only a few stops (or families of pipes) that are chosen to clarify the independence of the fugue’s voices.

An aside, but an interesting aside: Organs are of course wind instruments. When the wind first hits the lip of the pipe and the pipe begins to sing, there is a puff of air and white noise that organists and organ builders call “chiff.” Chiff often doesn’t come through well in recordings, but if you stand below a nice chiffy organ, so close that you can feel its breath in your face, the chiff will be quite noticeable. The chiff really helps with contrapuntal music, because it helps the ear distinguish the beginning of each note, the better to follow the lines of counterpoint.

Here is Simon Preston’s restrained and nerdly version of the organ fugue in G major, BWV 577. He has even slowed the tempo a bit to help your brain keep up with the four independent voices of the fugue:

There, then. Did that tax your brain? But it didn’t make you want to get up and dance, did it? The BWV 577 fugue isn’t called the jig fugue for nothing. Here is a very different recording by Diane Bish. Diane Bish does want to make a big noise and impress you with the power of the organ. She’s playing at a slightly faster tempo than Preston. She wants you to get up, clap your hands, and dance. In this version, hearing the separate voices of the fugue is more difficult. Diane Bish is concentrating on the whole:

Did that tucker you out? Need a glass of water?

The third version of the fugue is a novelty. It’s a performance by the Swingle Singers, who were quite a phenomenon in the popular music world when they came on the scene back in the 1960s. They’re going to sing the fugue. They’ve tinkered with the arrangement a bit, but when you hear human voices rather than organ voices singing the voices of the BWV 577 fugue, it’s a little clearer what Bach was up to and just what a genius he was:

Even if you don’t read music, take a look now at the top photo. That’s the first two pages of the organ score for the fugue. The entire fugue is only five pages. One interesting thing about this fugue is that rather than the highest voice (the soprano voice) beginning the fugue, the fugue actually begins with the tenor voice, played with the left hand on the organ. Even if you don’t read music, I bet you can track the main theme of the fugue through the first six measures of the score by observing how the notes move up and down. What’s a measure? Look at the vertical lines that appear between the notes every twelve beats. What’s a beat? I’d rather not try that in English at the moment, but your ear knows.

Another remarkable thing about this fugue is its unusual time signature — 12/8. I’d risk boring you and losing non-musicians if we got too deeply involved in the strangeness of 12/8 time. Musical “time signatures” can only be two-based or three-based. That includes multiples of two and three, like four and six, or eight and twelve. For three-based rhythm, think of the waltz (typically 3/4), in which you will surely count ONE-two-three, ONE-two-three as you learn the steps. A waltz is a three-based time signature. Now think of a march such as a Souza march. Typically a march will be in 2/4 time, and as you march you might count ONE-two, ONE-two, ONE-two, as your two feet strike the ground.

So what’s up with 12/8? It has characteristics of both two-based and three-based rhythm. This is because 12 is divisible by 3 as well as by 2. Over all, 12/8 has the feel of two-based 4/4 or 4/8 rhythm. But twelve can be divided by four three times. So you hear three-based rhythms merging into four-based rhythms. This will blow your mind, if you can hear it. Try it: Listen to the Diane Bish version again, and while she plays, rapidly count ONE-two-three, ONE-two-three, keeping up with the fast-moving notes. Now slow down and count at about half that speed. At half speed, your ear will hear ONE-two-three-four, ONE-two-three-four.

Now listen to the Swingle Singers performance again. About halfway through, a drum set joins the singers. Listen carefully to the drums. The percussionist is playing a four-based rhythm with one hand and a three-based rhythm with the other. That’s like rubbing your belly with one hand while patting your head with the other.

If you were able to hear the separate voices of the BWV 577 fugue at least some of the time, and if you were able to hear the fugue in three-base as well as four-base time, as though a jig is partly a fast waltz and partly a fast march, then congratulations. You’re on your way to becoming a fugue nerd.

And to my friend who is taking up music as an adult — and to all adults who might want to take up music later in life: I know that it may seem intimidating, but it’s an adventure. Most of all, let’s not let ourselves be intimated by fear of criticism or the hegemony of professionals (as much as we admire them and appreciate them). Music is like air and water, or language. It’s for everyone.

Which performance did you like the best? Were you able to hear the counterpoint at least part of the time? Could you hear both the three-ness and the four-ness of the 12/8 time signature?

Extra credit for advanced nerds: Can you see how we can calculate, mathematically, that the three-beats are occurring three times as fast as the four-beats? Try this as a thought experiment, or with another person:

Have one person, at a slow to moderate speed, count aloud in fours: ONE-two-three-four, ONE-two-three-four, ONE-two-free four.

Have a second person, counting much faster, count to three in the time it takes for the first person to say just one number: ONE-two-three, ONE-two-three, ONE-two-three.

Note that they will always both say “ONE” at the same time. What you now have is a three-based rhythm nested inside a four-based rhythm.

Here’s another way of doing the same thought experiment. Get two metronomes. Set the first metronome for a nice allegro tempo, say 120 beats per minute. Set the other metronome for exactly three times faster — 360 beats per minute. Now start both metronomes at exactly the same time. The faster metronome will say 1-2-3 for each click of the slower metronome.

In 12/8 time this odd rhythm is sustained through the whole piece. But three-on-four rhythm also occurs sometimes in passing in, say, 4/4 time, when three notes called “triplets” share the time allocated to one (or even two) 4/4 beats. Brahms is well-known for doing this in his piano pieces, in which one hand is playing a three-based rhythm against the other hand playing a four-based rhythm. In such situations, the pianist would be a fool to try to count it out. Rather, when you know how the piece should sound, the spirit of the music, guided by a disciplined ear, will pull you through.

Here is this rhythmic strangeness in a very different style of music, Brahm’s Intermezzo in A major for piano, opus 118, No. 2. Notice what happens rhythmically at 2:02. The left hand is playing six successive notes in the same time allocated for four successive notes in the right hand. Brahms then relieves the ear by breaking into a kind of four-part hymn at 2:44, with all the notes landing on the beat. Then, at 3:14, the rhythm runs to an even wilder six-against-four rhythm reachable only by the spirit of the music (and not easily by metronomes):

Here’s a single measure from this intermezzo, to show three-against-two, with the threes in the left hand and the twos in the right.

This cannot even be precisely scored. But do note how the middle C, which is attached to both the left hand and the right hand, is precisely on the beat in both lines, even though it’s the fourth note in equal time for the left and the third note for the right hand.

Don’t feel bad if this is hard to follow. It’s a tough problem for even for good musicians who are approaching this piece.