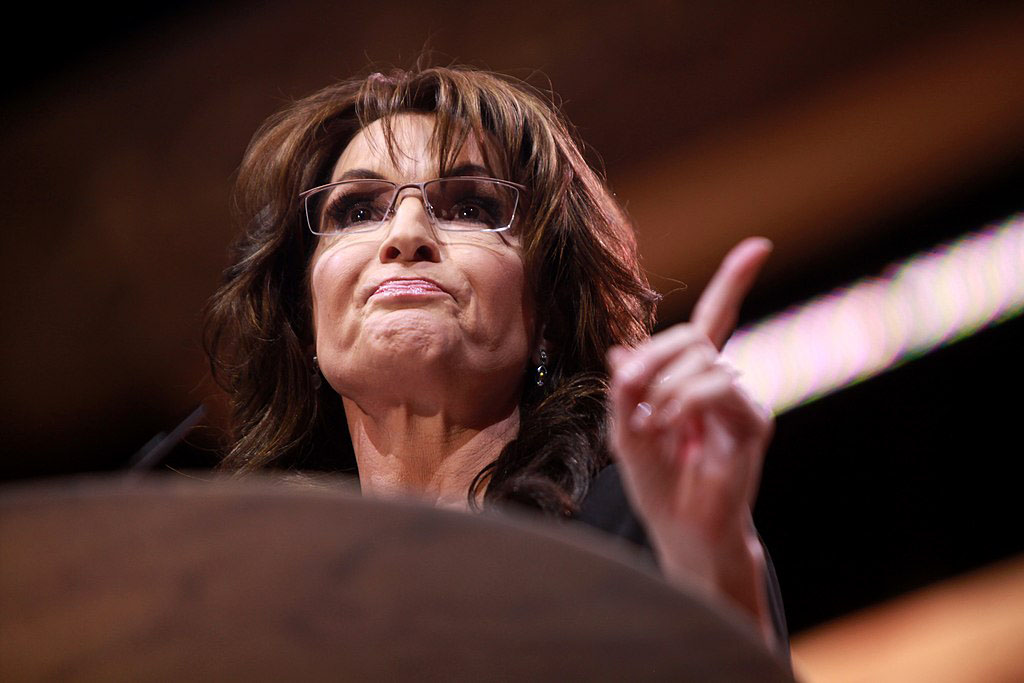

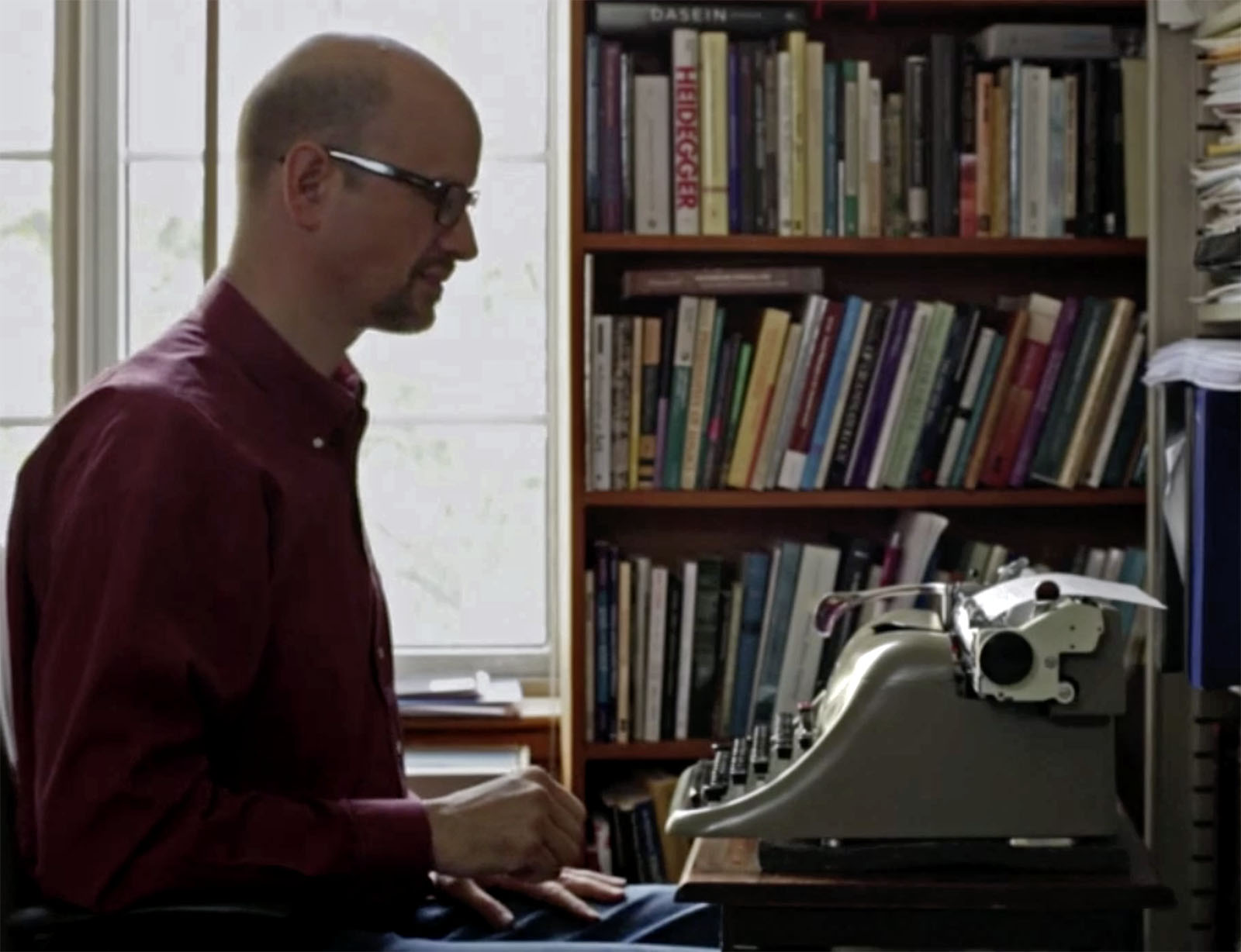

Tom Hanks in California Typewriter ⬆︎

Twenty years ago, typewriters were headed toward extinction. No new typewriters of any quality were being made. The surviving typewriters were deteriorating, unused and unloved, and many were being junked. Around 2010, typewriters started making a comeback, particularly among young people who were born after the Golden Age of typewriters who were intrigued by the typewriters’ elegance, magic, and retro quality. In 2017, Tom Hanks, who is a typewriter collector, made a beautiful documentary, California Typewriter. That documentary gave new energy to the movement to save, and use, old typewriters.

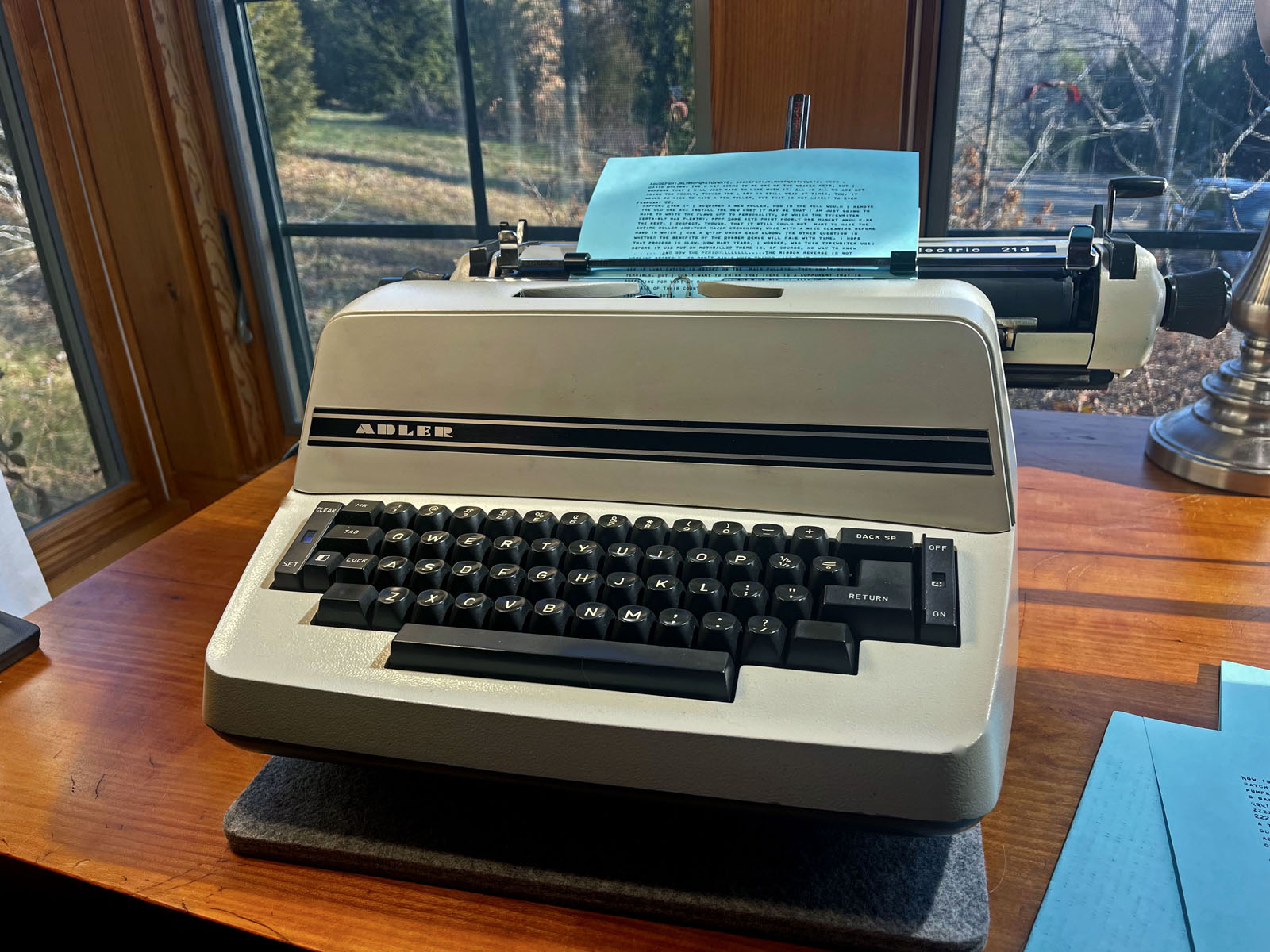

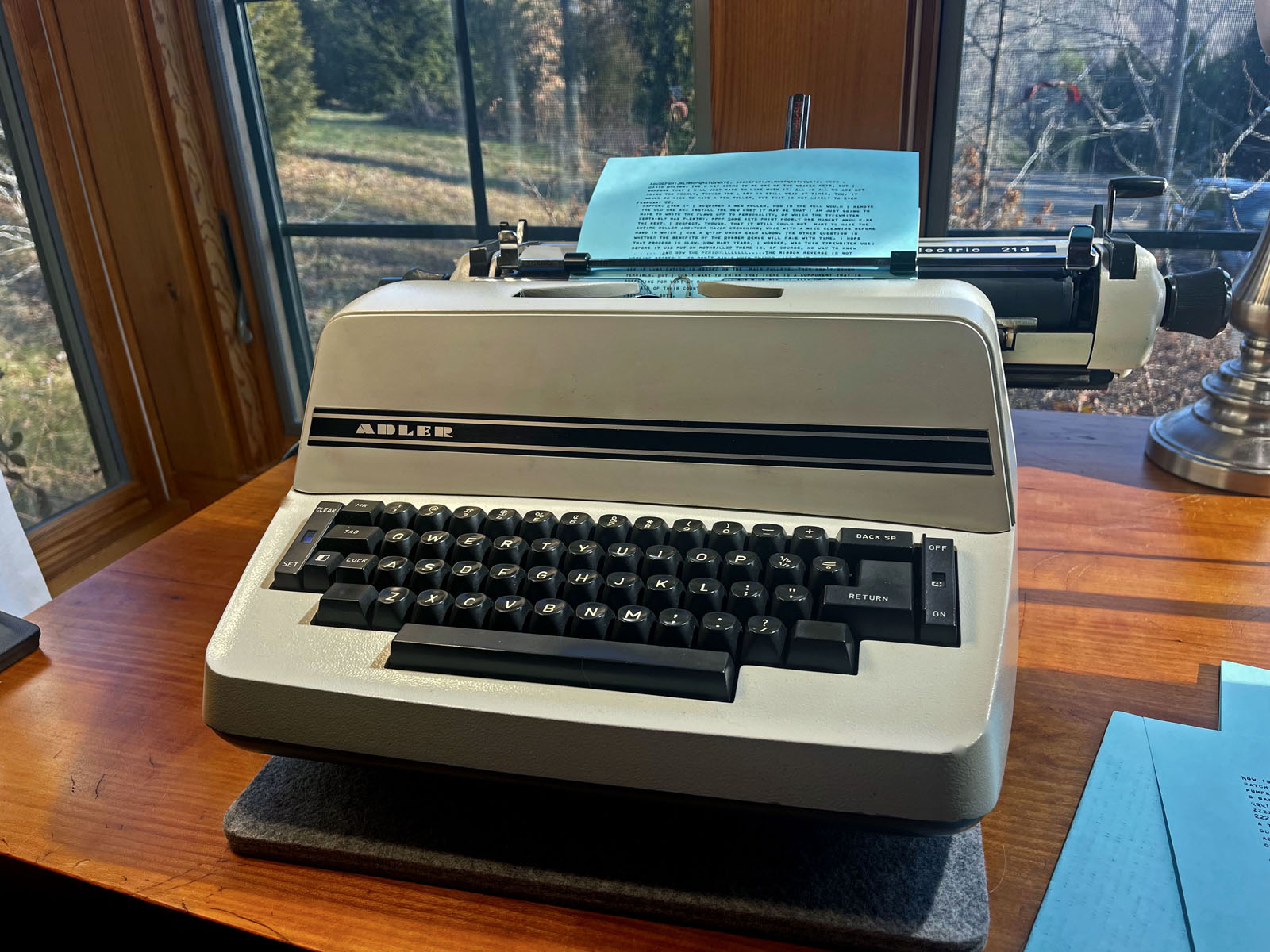

I acquired my first typewriter when I was eleven or twelve years old. My career was in newspaper newsrooms, so I have been around typewriters all my life. I confess that, around 1985, fascinated by computers, I stopped using typewriters. But around 1997 I salvaged an IBM Selectric III from the basement of the San Francisco Examiner and had it restored. A couple of weeks ago, while wasting time on eBay, I came across an Adler 21d electric — a huge office machine that weighs almost 45 pounds — and I bought it. It looked almost new, but it needed help. I’d collect typewriters if I could. But, unlike Tom Hanks, I don’t have anywhere to put 250 typewriters. Two or three well chosen, and well loved, typewriters will have to do for me.

California Typewriter interviews a good many people, but it focuses on a typewriter shop in Berkeley, California, across the bay from San Francisco. It’s horrifying, but the typewriter shop closed in 2017 not long after Tom Hanks made his documentary.

There is a line in the documentary, spoken by a poet or writer, “Typewriters are haunted.” That is it exactly. There is something about old typewriters that is alive, that has a clear personality, a kind of mechanical spirit that is made happy when someone uses them to write. One pushes words into a computer. But a typewriter’s magic is that it pulls the words out. I thought I must have been the only person in the world who sometimes writes on a typewriter, then scans the typewritten page to get the text into a computer. Thanks to California Typewriter, now I see that I’m not the only one.

The biggest problem with owning, using, or collecting typewriters these days is that the number of typewriter shops and typewriter mechanics continues to dwindle. With my IBM Selectric III, I was fortunate to get a full restoration done by a technician trained by IBM who was in his eighties at the time. That was ten years ago, and the Selectric continues to work perfectly. With my Adler 21d electric, I was able to get some help (and a diagnosis of the typewriter’s problems) from Ed at A.B.C. Office Systems near Asheville, North Carolina — the nearest remaining typewriter shop near me. Because I’m mechanically minded and have some pretty good tools, I was able to do much of the work myself to get the Adler typewriter back into working condition.

Manual typewriters are much easier to find and easier to restore. I have a fetish for electric typewriters, though. They’re faster, easier to use for hours at a time, and somehow they seem more alive to me. The electric typewriters made in the 1970s by Adler, in West Germany, particularly fascinate me. I regard those Adler electrics as the apex of typewriter engineering and manufacturing before the IBM Selectrics came out with the “golf ball” typewriters as opposed to the typewriters with little hammers.

As someone in the documentary points out, typewriters — good ones, anyway — will never be made again. The typewriters we have now, and the neglected typewriters that we can save, are the only typewriters we will ever have.

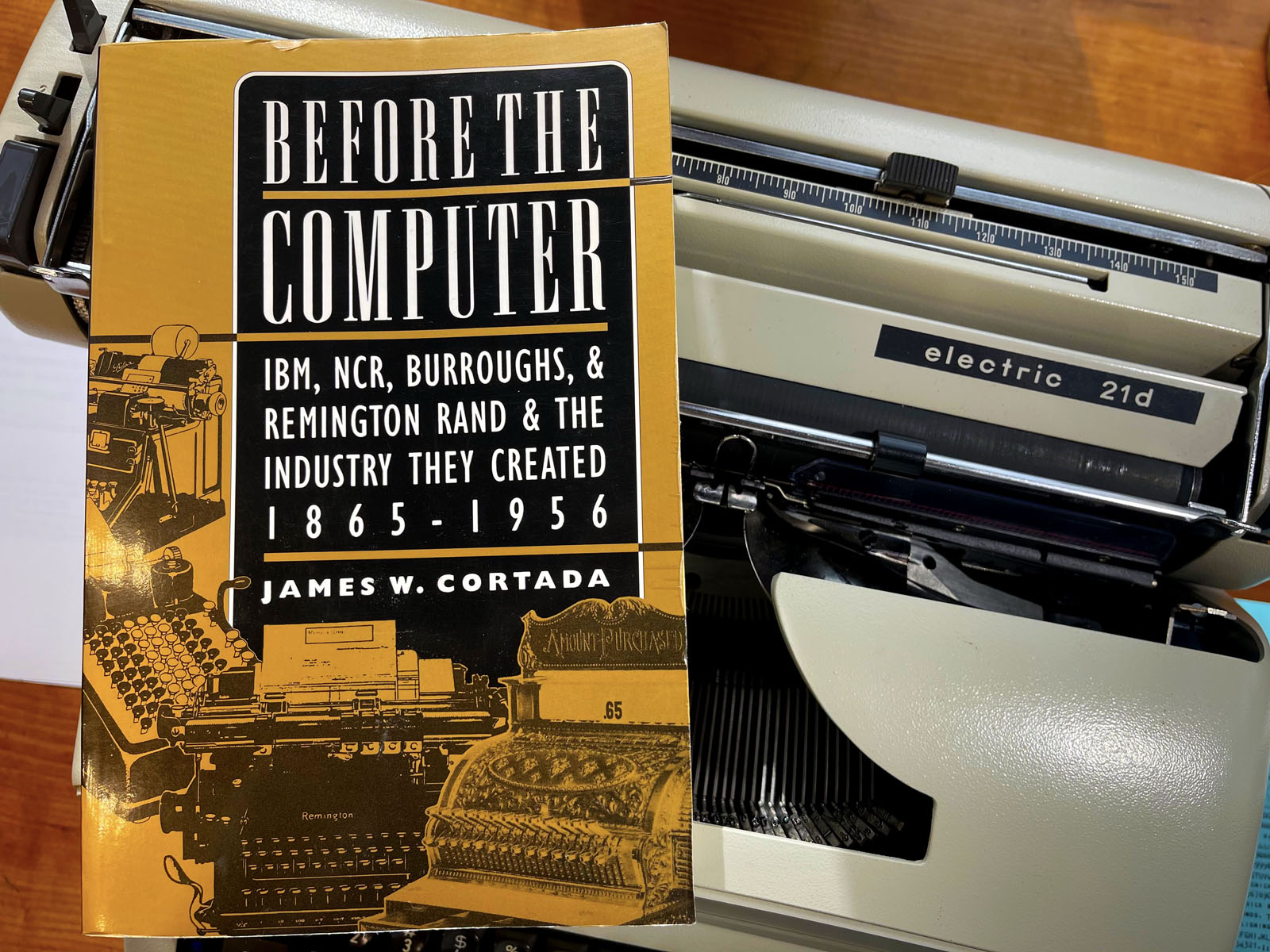

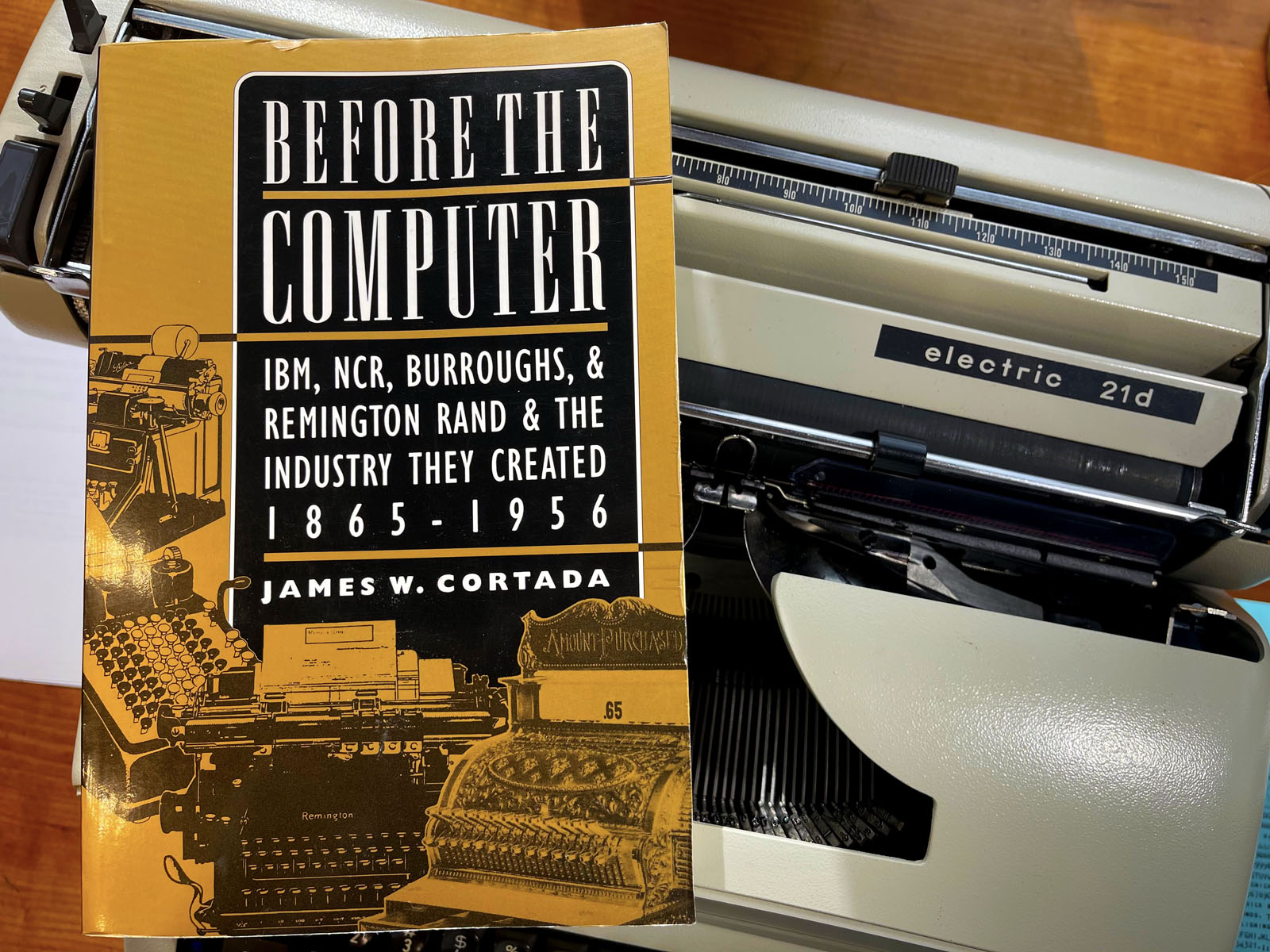

Often even typewriter lovers know very little about the long history of typewriters, or how the office machine industry, through the turn of the century and the world wars, led straight to the development of computers. Below I mention a book that discusses some of this history.

A writer writes, in California Typewriter ⬆︎

California Typewriter trailer, on YouTube ⬆︎

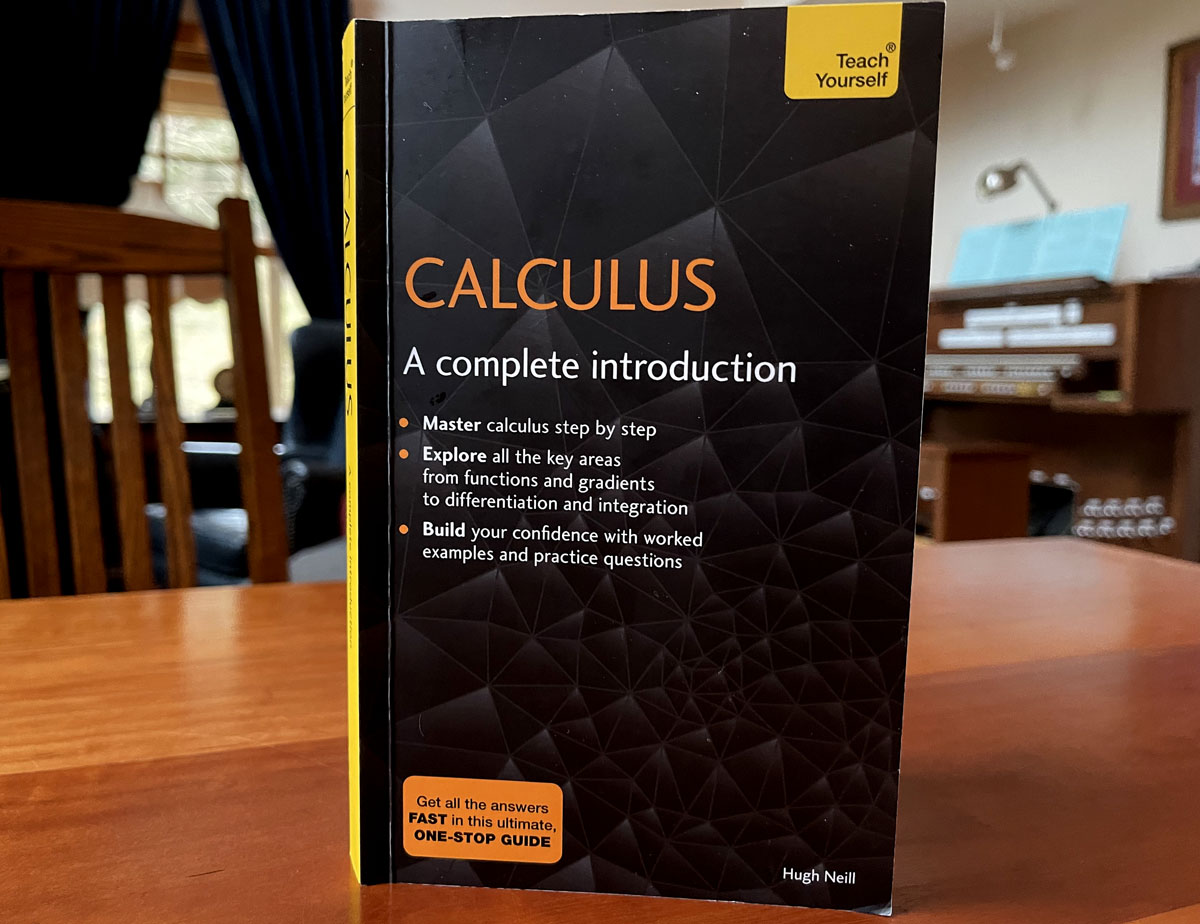

My recently acquired Adler 21d electric typewriter ⬆︎

My video on restoring my Adler 21d typewriter ⬆︎

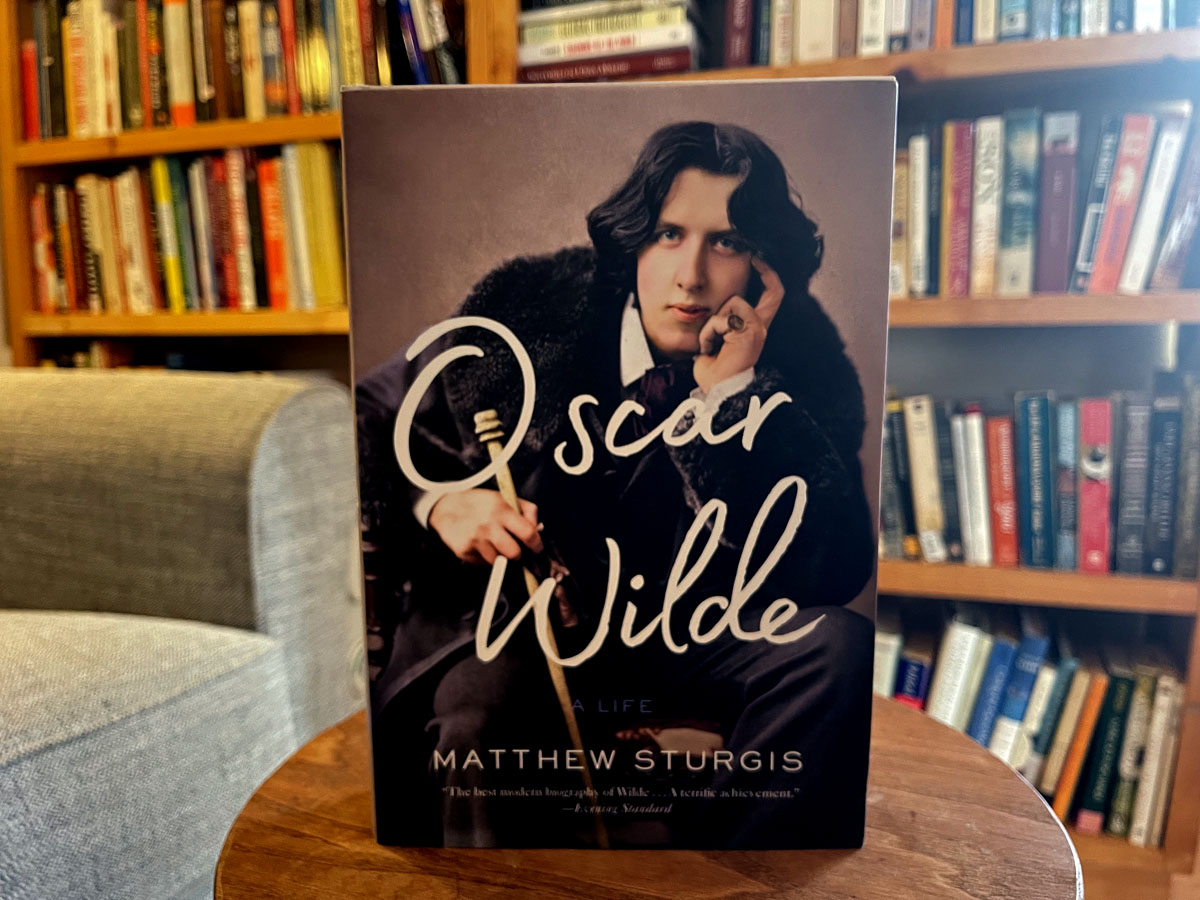

Before the Computer: IBM, NCR, Burroughs & Remington Rand & the Industry They Created, 1865-1956. James W. Cortada. Princeton University Press, 1993. 350 pages.

Typewriters were an important part of the technologies that led to today’s computers. This book concludes, in fact, that because of the extraordinary demand for efficiently moving data to support the allied armies during World War II, “one could conclude that democracy could not be saved without the typewriter.”

The machines that saved democracy — including typewriters, calculators, and the earliest computers — are in museums now, if they were lucky. Less lucky examples of some very beautiful mechanical technology are waiting for us to find them, preserve them, and even use them. The luckiest old machines of all those that are still being used.