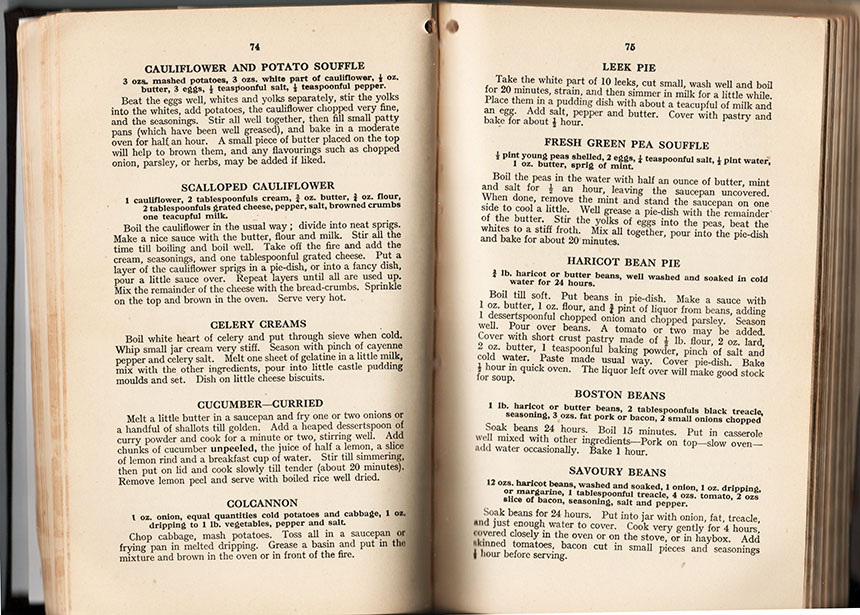

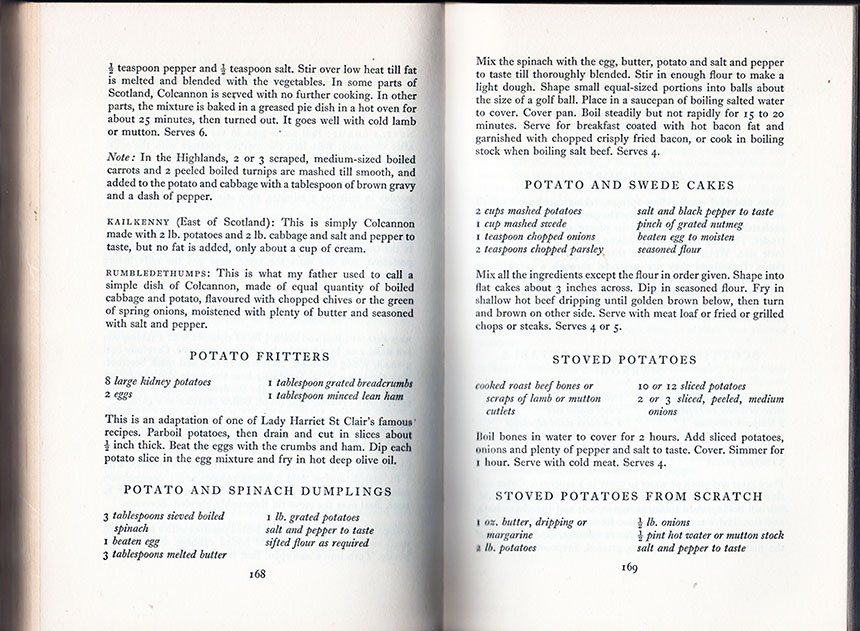

From the island of Gometra in Scotland. Photo from a trip in 2018. My DNA shows that my ancestors lived in places like this for 4,000 years. Click for high-resolution version.

The most important thing to know before choosing a DNA test is that there are three types of tests. They vary in cost, and each provides different information.

1. Autosomal DNA. About $100. This type of test looks at an individual’s DNA from both parents. It’s most effective for the past 300 to 400 years of ancestry. It estimates ancestry components, such as how much Germanic, Scandinavian, or African ancestry an individual has.

2. mtDNA. About $200. This is maternal DNA. Mothers pass it to all their children, but only daughters pass it on. It helps trace the path of maternal migration and contains information that can be traced thousands of years into the past. It does not provide ancestry percentages.

3. Y-DNA. Up to $500, depending on how many steps you want to sequence. This is paternal DNA. It is passed almost unchanged from fathers to sons. Mutations occur at a statistically predictable rate. It can show migration paths for thousands of years. It does not provide ancestry percentages.

Brick walls

When people research their ancestry through written records, things often get murky a few generations back. In the U.S., courthouse fires burned a lot of birth records and wills. Information on ship arrivals is incomplete. Amateur genealogists make a lot of mistakes. People often hit “brick walls” and can’t reliably trace a line any further.

My surname is Dalton. Records show pretty reliably that the first male Dalton arrived in Tidewater Virginia around 1699. His first name is not known for certain, but he’s known as “Timothy 1.” No one has ever been able to find records about exactly where he came from. For me, that’s a brick wall. We do know that his descendants migrated up the river valleys to the Charlottesville area, and then southward down into the Blue Ridge Mountains, where my father was born.

I recently bought an upgrade at FamilyTreeDNA to do the maximum possible sequencing on my Y-DNA. I waited more than two months for the results. The raw data is complicated, but now we have AI tools to help us interpret it. I use ChatGPT.

Because I have a great many genetic connections with Ireland, for some years I though that Timothy 1 might have come from Ireland. The new information from more detailed sequencing changes the story. Timothy 1 almost certainly came from northern England, probably Lancashire or Yorkshire. There are still a good many Daltons there.

Celtic to the bone

But here things get really interesting. I will never know their names or anything about their lives (other than what can be surmised from where they lived). But because Y-DNA is particularly useful for studying migration paths, we know where they lived for more than 10,000 years.

My paternal ancestors, then, were Celts. They arrived in Britain long before the Romans — around 2,000 BC.

Where were they when the wheel was invented, around 3,500 BC? They were almost certainly in the grassy steppes of Russia north of the Black Sea — maybe Ukraine. Much earlier, they migrated out of Africa and gradually spread across Eurasia. It was about 4,000 BC when they migrated through Turkey.

Thank you, wheel

It was the wheel that helped enable their migration westward into Europe. By 2,500 BC they had reached Germany and Poland. They probably crossed into Britain around 2,200 BC. Until Timothy 1 left for the American colonies, they lived in Britain for 4,000 years, most of that time in northern England. They were in Britain for the final stages of the building of Stonehenge.

Because of my love of languages and the history of language, the migration data allows some pretty accurate guesses about the languages they spoke. Working backward: English → (Early Modern English) → Middle English → Old English (Anglo-Saxon) → Brittonic Celtic (Cumbric/Common Brittonic; closest living cousin is Welsh) → Proto-Celtic → Proto-Indo-European.

Curse you, Iona

When were the poor souls Christianized? They probably were Christianized around 650 AD (or CE, as we now say). There were monasteries (such as Lindisfarne) that spread Christianity into northern England. It was in 635 AD when Saint Aidan came from the island of Iona (in Scotland) to found a monastery. I visited Iona in 2019, and I hated the place for the atmosphere of smug righteousness that clings to it. It was almost as though I realized, from somewhere deep in my genes, that the monastery at Iona had something to do with beating Christianity into my contentedly pagan ancestors.

They survived, obviously

Plagues and wars brought an end to many family lines. Between 1347 and 1351, the Black Death killed roughly 30–50% of England’s population. In some regions, mortality was even higher. My ancestors would have witnessed and survived the Norman Conquest — 1066. They probably took the Dalton surname between 1,200 and 1,400.

I can’t go home again

My first trip to Ireland was in 1996. As I explored the country lanes of County Kerry, drove over the mountain of Carrauntoohil, and looked out over the Atlantic toward Skellig Michael, again and again I had the feeling — this is home. It was some years later before I explored and thoroughly hiked similar terrain in Scotland. I’ve been all over England and much of Wales. As much as I love the Appalachian Highlands, it’s Ireland and the British Isles that feel most like home to me. Cows, the scent of the cool springs where milk is stored, cows in green pasture, heaths and bogs, the Atlantic crashing against rocky cliffs, potatoes, cabbages, oats, barley, hot soup, warm bread — I do believe these things are somehow implanted in our genes.

I’d move back there in a flash, if I could. But the realities of the modern world make that impossible. Timothy 1 could get on a ship and sail to America with no legal niceties to stop him. I can go back and visit, but the legal niceties are such that visas are good for only six months of a year.

If I could go back in time, I’d go find Timothy 1. He probably was a carpenter and small farmer. He probably didn’t inherit much. He probably heard that Virginia was a wide open land of opportunity (which it was). But I’d say to him: Please don’t do it, Timothy.

Note: ChatGPT 5.2 analyzed my DNA data and helped with the research for this post.