Ursula K. Le Guin

Amongst the literati and literati-watchers, much has been made lately of Ursula K. Le Guin’s war on Amazon. Her first bombardment in this war was last year in a talk she gave at the National Book Awards. A couple of months ago, she continued with a post titled “Up the Amazon” at Book View Café.

As much as I respect Ursula K. Le Guin, and as much as I like some of her (slightly too literary) novels, she has still failed to convince me that Amazon, as a major bookseller, is of the devil. She writes, “Sell it fast, sell it cheap, dump it, sell the next thing. No book has value in itself, only as it makes profit. Quick obsolescence, disposability — the creation of trash — is an essential element of the BS [best seller] machine.”

I can certainly agree with her on that, but I’m not convinced that the trail of evidence leads to Amazon.

Has Le Guin, I wonder, ever been to a Walmart and examined the books on sale there? Or the grocery store? In Googling for “books at Walmart,” I came across a blog post by an author named Keli Gwyn. The title of the post was, “Six Reasons I Get Excited When an Author Gets a Book in Walmart.” She writes: “Of the few books that make it into Walmart, most were written by big-name, best-selling authors with a tremendous track record of sales. The noted exception is a series of books from a traditional publisher that has already gone through the process of getting approval from Anderson Merchandising.”

Uh-oh. Who is Anderson Merchandising? She writes: “Getting a book into Walmart is difficult. According to the Walmart website, each vendor of any product sold in Walmart must go through an extensive proposal process. Those selling books must contact Anderson Merchandisers, the company that stocks the book sections in Walmart stores.”

Who is Keli Gwyn? In her blog, she describes herself as “an inspirational historical romance author.” She says, “My favorite places to visit are other Gold Rush-era towns, historical museums and Taco Bell.”

I just puked.

Walmart sells very few titles, only mass-market things that will sell by the millions. Amazon sells everything, including titles that haven’t sold a copy in the last five years.

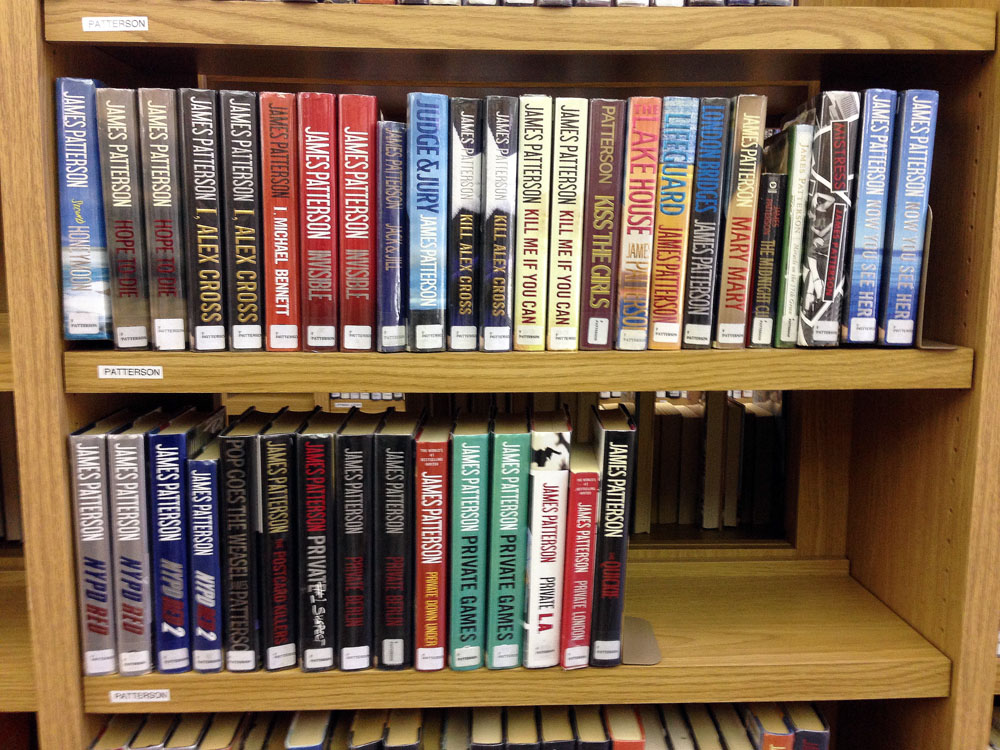

But there’s not just Walmart. I wonder if Ursula K. Le Guin has visited public libraries in America’s so-called heartland. She will find that half (I don’t think I’m kidding, though I have not done an actual count) of the books are inspirational historical romances by crank-’em-out authors. These crank-’em-out authors completely dominate the fiction shelves, with the titles of a single author sometimes two or three levels deep. I can’t tell you how many times I have walked the entire length of the fiction shelves in public libraries, A through Z, and found absolutely nothing to read. Even at the nearest used book store in Winston-Salem, which is pretty big, the shelves are filled mostly with mass market paperbacks by crank-’em-out authors.

Just a few days ago, I was in the nearest Barnes & Nobles. It was a Sunday. There were a lot of people there — the local literati. I make no attempts to keep up with any genre other than science fiction. But judging from the long science-fiction section with books by a great many authors, science fiction publishing seems to be doing as well as it ever did. (Though it puzzles me why Barnes & Nobles stocks so much science fiction and local libraries almost none.)

Anyway, I strongly suspect that Le Guin is blaming Amazon for phenomena that have much longer and deeper roots. Is Amazon making people dumber? Or are people just getting dumber? Is the market making people dumb? Or is the market just giving dumb people what they want? It’s sugar water in the grocery stores and Donald Trump on TV. Ursula Le Guin, I suspect, has lived in an ivory tower surrounded by academics for so long that she simply doesn’t know how dumb people are.

Amazon is the one place where you can buy any book, from any publisher, including university presses. If the book you want is out of print, you’ll be presented with a list of small booksellers who will sell it to you used, cheap, and get it to you fast. There have been a number of times when I needed a copy of an out-of-print book published in the 1930s and 1940s. I have always found it on Amazon. More than half the books I buy are from university presses. Would Ursula K. Le Guin really want me to stop buying these books on Amazon?

Of course, Le Guin’s issue is not about Amazon’s selling of books but rather about how Amazon’s marketing power is influencing publishers toward publishing crap, while also diminishing the compensation of authors. That may be an unintended consequence of Amazon’s market power, but all that Amazon really is trying to do is to keep the price of books down, in order to sell more books.

Le Guin accuses Amazon of “controlling what we read.” How could that possibly be, when Amazon sells millions of titles — more than anybody? Searching for any title, author, or subject you want is as easy as typing 1-2-3.

Notice also the slight disdain in Le Guin’s tone when she speaks of books that are self-published. She knows that, on principle, the ability of authors to easily publish their own books is something that she must approve of. But still I get the clear impression that it annoys her, because that too depresses the incomes of established authors with regular publishers and royalty streams.

One of my biggest disappointments recently where books and stories are concerned was the new “Poldark” series on British television (PBS in the U.S.). It is based on a series of very fine novels by Winston Graham, and a British television production of “Poldark” in the 1970s got it right. The 1970s television series was remarkably true to Winston Graham’s novels.

But Winston Graham died in 2003. The new television version of “Poldark” had been turned into an “inspirational historical romance.” Winston Graham must have rolled in his grave. The show was embarrassing to watch at times. It lingered on anything sentimental and edited in shots of flowers blowing in the wind to make sure we got it. The script focused mainly on romantic entanglements, attending to other parts of the story only when it couldn’t be avoided. Characters that were beautifully developed in Winston Graham’s novels and in the 1970s Poldark were severely neglected — because they didn’t have a romance going. Whoever adapted that screenplay would better serve the literary world by boxing up romance novels for overnight shipping at Amazon for $15 an hour.

Is it somehow Amazon’s fault that British television, PBS, Walmart, and the local libraries all now kiss the ass of the market for “inspirational historical romance,” or vampire novels (now out of style), or zombie novels (still in), or stuff written by authors who wear funny hats and crank out their plots while sitting in a Taco Bell? Even George R.R. Martin is whoring in the zombie market.

That in itself is a big part of the problem — authors who are whores to the market: romance writers, vampire writers, zombie writers, authors who crank ’em out so fast that they may have twenty or more titles in a single rural library. In J.R.R. Tolkien’s letters, written during the time when he was toiling away on Lord of the Rings, unsure of when and how it would be published, he often remarked that there was a very small market for what he was writing, but that those who wanted it were starved for it. And that, of course, is one of the reasons why Tolkien’s trilogy is so great. He wrote the story that was in him to write, for the few who were starved for it. And when he stopped having stories to tell, he stopped writing.

Is it necessarily bad that publishing is a big business? Niche readers know where to look. For the first time in the history of publishing, that which bigger publishers turn down now finds its way to small presses or gets self-published. George Herbert’s Dune was rejected by more than 20 publishers before Chilton, a publisher of car-repair manuals, finally picked it up. The publishing industry has always made mistakes. I don’t think Amazon is to be blamed for the existence of a mass market and the junk that feeds it.

In my opinion, if the publishing market can make an author filthy rich, then that author is done. Think of Stephen King, Anne Rice, Orson Scott Card, Tom Clancy, or Danielle Steele. Authors ought to be a little hungry, and they ought to be terrified of what the market will think of their book.

I think that Ursula K. Le Guin is being more elitist than she realizes. Maybe she should visit a Taco Bell. Many authors (including most dead authors) can’t get their books into brick and mortar stores like Barnes & Noble, which mostly carries what’s new, or even into neighborhood independent bookstores. I admire independent books stores, but if we read only from their thin stock, we’d be only slightly better fed than if we bought all our books, along with our sugar water, at the grocery store.

I will buy books wherever I damn well please. And the author who wrote those books, no matter who they may be, probably will be grateful for the sales.