In my ongoing efforts to break out of the same-old-breakfast routine, this morning I attempted baked grits with cheese, blackened beans, and fried apples. The beans were terrible. I had never attempted that sort of seasoning before, and I don’t think I was quite clear on the concept. And though the grits were good, I went too far in my effort to make them a comfort food. Less cheese and less butter would have been better. I’d give myself a B+ for the concept and an F for the execution.

Month: January 2011

The Anglican choral tradition

An article in a recent New Yorker magazine made me even more appreciative of the choral tradition of the Anglican church, not to mention more glad that I had the opportunity to sing in the choir at an Episcopalian Christmas service last month. The article is in the Jan. 10, 2011, issue: “Many Voices: Blue Heron brings a hint of the Baroque to Renaissance polyphony.” The article is available on the New Yorker web site, but a subscription is required.

The article is about some newer choral groups who have been exploring the same historical terrain as the Tallis Scholars, who have been around since the 1970s. The article contains this rather intriguing line: “Likewise, the austere allure of the Tallis Scholars is inseparable from the Anglican choral tradition, which owes much to Victorian values.” This reference to Victorian values is left unexplained, but I assume it means that, even though the roots of Anglican music lie deep in the past, in the Medieval monastic tradition and in the Golden Age that occurred during the reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, Anglican music nevertheless was affected by the theological — and musical — emphasis on the more personal forms of salvation that marked the 19th Century.

I was raised in the Southern Baptist Church, the music of which largely comes from this 19th Century tradition. My first organ teacher was a Moravian and organist at a small Moravian church. I sometimes substituted for her when she was on vacation. Though not as ancient as the Anglican musical tradition, Moravian music reaches back a century or two earlier than the Baptist tradition, to the time of J.S. Bach.

It is strange that, though I’ve been singing since I was a child, and though I used to accompany small congregations, I had never been in a choir until last month. I’m thinking that I’d like to do it again at Easter. The YouTube videos to which I’ve linked here capture some of the thrill of singing in a choir, especially the many YouTube videos of King’s College Cambridge. Practicing the organ was always such lonely work, usually done in dark, underheated churches. But practicing with a choir is a very different thing.

When rehearsals started in November for St. Paul’s Christmas program, I almost convinced myself that I’d never learn the bass parts for 45 or so pages of music. I wasn’t alone, though. Everyone in the choir, including the professional section leaders, had lots of work to do. But then something stunning happens at the final performance. Not only did the members of the choir know the music, they’d even memorized most of the words. At last they could take their eyes off the score and watch the director. And no longer is the director playing the role of the kindly tyrant. With the director’s back to the congregation (which was packed for the Christmas service), they can’t see that he is smiling at us, winking at us, gesticulating when his hands and arms are insufficient to communicate with us. Suddenly we are totally under his control, attentive and obedient. Every voice starts precisely on the beat. When he requests a crescendo or a ritardando, he gets it. We hold the last note, forte, nearly out of breath, the power of the organ supporting us, but not until the director makes a little chopping gesture with his hands do we stop, all precisely together. The sound reverberates through the church. I dare to shift my eyes off the director now and see that members of the congregation are smiling. We almost had them on the edge of their seats. Choral music does that to people. Sometimes, listening to an organ, especially an infectiously complex fugue by J.S. Bach, I find myself hyperventilating in sympathy with the organ and the huge amount of breath it is expending. Choral music, too, pulls us in somehow. It makes us want to sing with other people. When the choir comes up for air, so does the congregation.

Recently, after watching the movie Winter’s Bone, I was trying to explain to a friend the distinction between the music of the high church (the Anglicans) and the low church (pretty much everybody else). Despite the differences, these musical traditions have much in common, and both are wonderful. Part of the appeal of Winter’s Bone was the soundtrack, with a completely unexpected and beautiful performance of the very low church “Farther Along.” I sang along with it, in harmony. I’m linking to that as well.

Low church and high church — both are rich, beautiful, and deep. Even a pagan must pay his respects.

YouTube: The Tallis Scholars sing Thomas Tallis

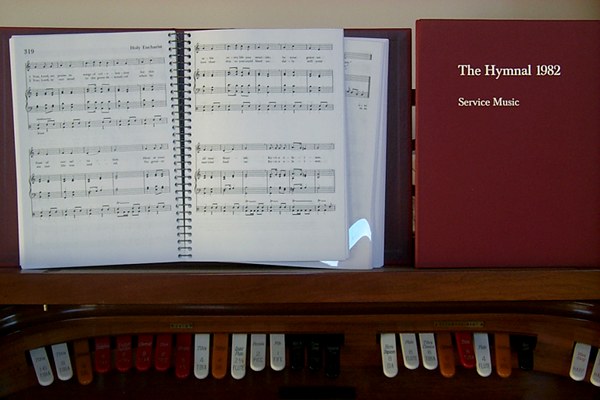

My new Episcopal hymnals, ordered from Amazon

YouTube: Farther Along, from the soundtrack of Winter’s Bone

Rehabilitating the rabbit patch

Ken piles debris onto the brush pile. We hope the rabbits like it.

If I myself had to do the work of tidying up the grounds around Acorn Abbey, it probably never would get done. Ken has been plugging away at this work for a month now. The area most in need of cleanup is a band of thicket on the lower side of the abbey, between the house and the woods. This area had all its pine trees removed in the spring of 2008. The stumps are still there. The soil has not been disturbed. All the limbs and debris were still on the ground. It was a rather unsightly area, difficult to walk through because of the briars and debris. But it’s potentially a beautiful area, and it’s excellent rabbit habitat.

Ken and I negotiated on what would go and what would stay. Ken has a soft spot for the young pine trees, for example, whereas I wanted the pine trees gone to leave space and sunlight for the young hardwoods that are eager to get a start. The pines, we finally agreed, would go. Ken also removed all the briars and vines that were choking some of the young trees. He left the blackberry bushes. All the debris he put into brush piles, which we think will make excellent refuges for rabbits.

Part of the process, also, was identifying and marking the young persimmon trees — fruit bearers. There were three. Ken cleared especially carefully around the persimmon trees to give them room to grow, and to make room for collecting the fruit in the fall.

All of this is winter work. The plan is to get it all done before all the spring gardening and yard work have to be done.

One of the nice discoveries was that there are several small stands of mountain laurel — one of the symbols of the Appalachian range. We’ll mulch around the laurel to encourage it to grow. The area is moist. There also is some fern and moss.

All in all, it’s an ecologically interesting and diverse area. The plan is to let the area return to its default state: hardwood woodland. The woods at present are about 75 feet below the abbey. When this area returns to woodland, the woods will come right up to the edge of the abbey’s yard, 25 and 30 feet below the house.

All the signs of the fact that the abbey was a construction project two years ago are rapidly disappearing. The established, timeless look that I want is beginning to emerge. It’s going to be a beautiful spring.

The red tape marks a persimmon tree.

The grassy slope to the left is the edge of the abbey’s lower yard.

His own private Idaho

Have I mentioned that Ken is weird? It’s not enough that he’s immersed in the quiet and solitude of Acorn Abbey, where there hasn’t been a car on the road in a week and where the only sound on a winter afternoon is the quiet hum of the heating system and the occasional patter of cat feet on the stairs. When he writes, he has the habit of surrounding himself with a shroud to further close out the world. I’ll keep this short, so that the click of the keyboard upstairs doesn’t disturb him too much.

The ground is too soft from the melting snow to do much work outside right now. Ken knows how finicky I am about excess traffic that could wear paths or kill grass. Yards are very vulnerable this time of year. Very soon, though, we’ve got to order seeds for the early garden. Spring is not that far off. The daffodil shoots will start popping up in another six weeks or so.

A country-style no-egg breakfast

Here’s a serious attempt at making a low-cost, country-style, no-egg, no-meat breakfast with a little excitement to it. The beans are homemade baked beans, made in a crock pot using organic white beans bought in bulk at Whole Foods. The sausage is my homemade vegan sausage based on mashed soybeans and wheat gluten.

The yellow grits were bought in bulk at Whole Foods. Southerners eat white grits, but I’ve been experimenting with yellow grits. They have a bit more flavor than white grits, and a creamier texture. They’re even a fairly satisfying egg substitute if you put a nice dab of butter on them. Don’t use butter when you’re cooking them, though. You want only 1 portion of grits to about 4 portions of water, with some salt. Boil them for at least 20 minutes, or until they’re properly thick, then let them sit for a few minutes before serving.

The biscuits are my usual vegan biscuits, made with about half unbleached white flour and half whole wheat flour. In the biscuits I use olive oil or refined palm oil as the shortening, and I make vegan buttermilk by clabbering some soy milk with a teaspoon of cider vinegar.

One of the commenters here, Brother Doc, suggested fried apples for breakfast. That was an excellent suggestion.

This is a vegan breakfast except for the butter on the grits. I also used butter to fry the apples.

Hawk 0, Chastity 2

Chastity, the day after the second hawk attack. Her eye is OK, but she’s squinting from the hawk-peck wound just below her right eye.

The hawk came back.

Once again, it went for Chastity. Ken found her lying on the ground beside the chicken house, in a state of shock. He picked her up and put her inside. There was some sign of injury to one of her wings, but no blood. And there was a hawk-peck wound just under her right eye that caused her eye to swell shut. A day later, she was squinting, and we could see that her eye was OK. Today, two days later, her eye is almost back to normal except for the scab underneath it.

Chastity seems depressed, but she’ll make a full recovery.

Now what will we do. Clearly the hawk is not going to give up on trying to eat the chickens. Besides, hawks waste chickens. I understand that they eat the brain and lungs and leave the rest. Even worse, Ken has seen evidence that the hawk has built a nest at the edge of the woods right below the abbey. I would have assumed this to be a squirrel’s nest, but would a hawk enter and settle down into a squirrels nest, as Ken saw it do? I doubt it.

For now, we’re letting the chickens out only when we’re there to shepherd them, while we try to figure out what to do. We could put up a scarecrow and a fake owl, but I doubt that would be very effective. Some people report success stringing fishing line above the chicken lot, but I’m not sure that’s practical here. The fence is large (almost 400 feet). Though the fence is 8 feet high, I doubt we could string fishing line in such a way that it wouldn’t sag and strangle us as we worked in the garden. I’m looking for new ideas for defenses and trying to figure out what’s practical.

I’m pretty sure that it’s illegal under state and/or federal law to kill a hawk. That’s out of the question.

In so many ways, it’s exciting to live in a place with so much wildlife. But I never guessed that it would be such a struggle to defend the chickens and the garden. Between the deer, the groundhogs, the hawk, the fox, and the voles, everything wants to move in and eat us out of house and home.

The hawk at the edge of the woods, only 35 yards from the abbey. Photos by Ken Ilgunas.

Hawk nest or squirrel’s nest? Ken saw the hawk actually enter and settle into the nest.

Has a fox family moved in?

There is very good evidence that a fox family has moved in just downhill from the abbey. While clearing brush, Ken came across what appears to be lots and lots of fox poop. Nearby, in a deep brush pile (near a ravine where the bulldozer pushed the stumps when trees were cleared for the abbey three years ago) we also found the entrance to their den.

The poop looks like dog poop. It has evidence of fur in it and clearly is carnivore or omnivore poop. Also, early one evening a couple of months ago, when Lily was growling at the window, I turned on the outdoor lights and saw a cute little red fox right in front of the house. New neighbors, I feel sure.

It remains to be seen whether the foxes will be a bother. They’d have a hard time getting to the chickens. The henhouse is secure, and though it would be possible for predators to dig and get under the fence, so far we’ve seen no signs of that. The chickens are always locked in the henhouse at night. Neighbors report having seen foxes, and a neighbor’s game camera got a photo of a nocturnal fox, but no one has seen a fox during daylight.

So I guess we’ll take a wait-and-see attitude toward the fox neighbors. I would never shoot a fox, but I would not hesitate to harass them and encourage them to move away. The harassment strategy seemed to work with the groundhogs. The groundhogs were raiding the garden. Steady harassment (yelling, chasing, shooting a pellet gun into the ground near them, etc.) caused the groundhogs to move on.

But how in the world will we build up a rabbit population with foxes living right up against the backyard?

Vegan barbecue, Lexington style

Vegan meat analogs have become a staple around here. The most recent experiment was an attempt at Lexington-style pork barbecue. There’d be no mistaking it for the real thing, but it was very good. We even ate the leftovers for breakfast (with fried apples, yellow grits, and warmed-over biscuits).

The basic ingredients for the meat analogs are legumes (either cooked, mashed soybeans or garbanzo bean flour), ground nuts (usually brazil nuts), and wheat gluten. The proportions and seasonings are varied according to the kind of analog. Mashed soybeans makes a nice analog of dark meat, and garbanzo bean flour makes a nice analog of white meat. The addition of ground nuts makes a flakier texture (like meat loaf), and the reduction or omission of the ground nuts makes a more chewy texture (like chicken or pork).

I used a homemade barbecue sauce, Lexington style (as in Lexington, North Carolina — ground zero for the type of pork barbecue that is made in this area of North Carolina). The ingredients are cider vinegar (sometimes diluted with water or apple juice), ketchup, brown sugar, black and red pepper, and salt. If you Google for “Lexington barbecue sauce” you’ll find lots of recipes. The smokiness of proper barbecue was missing. Liquid Smoke is on my shopping list. I hope that will help.

I served the barbecue with roasted potatoes, slaw, and homemade rolls. Good eatin’!

The day the hawk swooped down

By Ken Ilgunas

I was sprinting toward the fence gate. With arms pumping, eyes bulged, and teeth clenched, I flung one foot forward after another—my shoeless soles making soft thuds in the grass as the wind swept my hair back, revealing my otherwise cleverly-hidden and regretfully-high hairline. “NOOOOOO!” I bellowed. “THE CHICKENS!”

It was a clear, brisk afternoon. Moments before, I had been standing on David’s porch, looking out at the garden while talking with my father on the phone.

As I watched a shadow move across the yard, I couldn’t help but tune my father out. The shadow, at first, was small—maybe the width of a mason jar. But as it approached the garden fence, it got bigger and bigger—like a the shadow of a UFO descending to earth, ready to collect samples for examination, experimentation, and an obligatory probing.

The shadow—moving at lightning speed—advanced toward our three chickens who were close together—as they always are—innocently scratching and pecking the ground near one of the apple trees. That’s when I saw the shadow’s source. It was a hawk, mottled black and gray with wings outstretched, exposing a bone-white underside. It lowered its claws like airplane wheels and aimed its beak at Chastity, one of our two dark chickens.

The hawk clenched its claws into the Chastity’s back, and began flapping its freakishly large wings in hopes of carrying his meal to a more appropriate venue.

The chickens have almost no way to defend themselves against a bird of that size. They can’t fly very far, their beaks are too small to fight back, and the coop—their only recourse to shelter—was too far way. Our chickens, though, have one thing going for them: they are—and I don’t know how to put this lightly—fat. I wouldn’t go as far to call them “obese,” because obesity suggests poor health when our chickens, thankfully, are as healthy as can be. But they are, nonetheless, fat. And I don’t say that disparagingly. If I was a rooster ambling through the property, I’d likely be unable to continue on without pausing to admire their plump, healthy, feminine curves, before communicating my ardor to them with flagrantly obscene roadside catcalls.

The hawk raised Chastity’s body only about a foot into the air before they both came crashing down to earth.

It was at this point that I screamed, “No! The chickens!” I dropped the phone and ran to the fence where I hoped to put on a display of acrobatic martial arts maneuvers that—because I’d seen so many kung fu movies in my childhood—I figured were second-nature to me by now.

What was my poor father thinking? “No! The chickens!” was the last thing he’d heard before I dropped the phone onto the deck’s wood planks and took off running. Perhaps he was left shuddering in horror as he imagined his firstborn begin pecked to death by a flock of ravenous chickens. He’d picture me like a man covered in feathered flames, stumbling drunkenly as 20 of them clutched my every morsel of flesh.

But it need not be said that I was running and panting and girlishly screaming to save the chickens.

It might seem odd for a man to get so worked up about an animal that people eat every day, especially an animal that everyone knows has no personality, an animal that is perceived to be clone-like and characterless.

Meat becomes easy to swallow when we think of animals more like thoughtless robots, and less like sentient beings like ourselves. So who cares if a chicken—that’s eaten by millions of people every day—becomes hawk food?

I never thought I’d say this, but I adore chickens. Well, I adore at least three chickens.

Whenever I walk into the fenced enclosure where the chickens roam free, the three of them (who I call “the girls”) will come rushing down the hill—running like diapered toddlers on wobbly legs—to greet me like puppies. They’ll surround me, and look up into my eyes, as I lavish their feathers with compliments. At night, when I go to lock them up in their coop, I can hear them all cooing at the same time—a communal loquacity that brings to mind a circle of grandmothers with balls of yarn in their laps who talk purely for the joy of talking, unconcerned with whether or not anyone’s really listening.

Much to my surprise, I’ve learned that each of “the girls” is by no means a “clone”; they each have their own distinctive personality.

Ruth—the red chicken—is easily the dimmest of the three. In her wide blank eyes, you can see a mind that is ripe for conversion. Because she cannot think for herself, she can be swayed to the dark side, as well as the good. Her morality depends entirely on whatever the dominant ideology of the group is. Ironically, despite her dimwittedness, she also exhibits the most curiosity of the three. Every morning last summer—when I had to forcefully remove Patience from her nest (because Patience was in some weird and unhealthy nesting mode)—Ruth would always stop what she was doing to come up and watch as I pushed her broody friend out of the coop. During that time, Ruth used to reign supreme at the top of the pecking order when they all lived in the coop, constantly tormenting those bold enough to eat before her with sharp pecks to the neck. The two darker chickens, however, have benefited more than Ruth has from grazing in the yard, and they—with due justice—have since pushed Ruth down to the bottom of the order. Ruth—desperate to dominate somebody—began pecking our feet, but with a couple of artfully placed kicks to her rear, we’ve avoided succumbing to the tyranny of ruthless Ruth.

Patience—the plumpest of the three—is like the crazy gay aunt of the family. You know the aunt—the one who has a mysterious personal life about which no one in the family knows anything, except that she has eccentric hobbies like skydiving and some weird new Asian religion. You love it when she shows up for family gatherings, only because you have no idea what to expect when she’s around. The more conservative members of the family write her off as insane, but only because they feel threatened by some faint hint of brilliance in her eccentricity. Patience is constantly making strange noises, and flapping her wings at all times of the day. As mentioned above, she spent the whole summer sitting on her nest for no useful reason. Patience is my favorite and the most dog-like of the group, loyally following me around during my rounds in the yard. She’s taken a special liking to me, which is especially evident when she turns her back and squats in front of me, as willing hens are wont to do in front of courting roosters. Of course I haven’t taken her up on the offer, but I’m always flattered nonetheless.

Chastity—the dark chicken who was targeted by the hawk—is the most stoic and matronly of the bunch. While Ruth’s eyes sometimes appear cold and reptilian, Chastity’s are human-like, sometimes even sagely. She carries herself with more awareness and self-composure than the others, rarely permitting herself to become involved in petty, pecking-order politics—not because of highbrowed haughtiness, but because she is unconcerned with the trivialities of the present. She seems to have been blessed with an empathy that comes from living close to nature and her kind, but also a wisdom—bestowed to her by noble blood—that allows her to “remove” herself from the limits of the physical world and to shift her thoughts to a higher plane. From this vantage point, she can see how she fits into the larger scheme of things. Chastity is both smarter and stronger than Ruth and Patience, and while some chickens would use this power for personal gain, or to revel in the perverse glee of subjugating others, Chastity, rather, sees her role—not as an “opportunity”—but a duty to care for those weaker than she—a duty that she is—by honor—obligated to accept.

My Chastity. My dear Chastity. I saw her flipped upside down in the air with wings flailing, now headed to the ground headfirst. The hawk—unable to pick her up—had his claws planted on the ground now, figuring he’d devour Chastity on the spot. He snapped his beak at the heap of feathers until he became aware of the moaning apelike figure that ran after it with beak-dropping haste. The hawk left Chastity on the ground, took off for the trees, sat on a limb, and looked down on its kill, eager for the chance to strike again. Chastity was lying down and motionless, huddled with the other two chickens.

I was devastated. David, at the time, was in Winston-Salem shopping for groceries. I knew it would break his heart when I had to tell him that one of his chickens had been killed.

I wanted revenge.

I could still see the hawk, brazenly perched above. David has a pellet gun, I remembered. That would do the trick. I rushed back into the house, found the rifle, and opened the canister of pellets to load it up. Having never grown up with guns in my house, I hadn’t the slightest idea how to load it. Puzzled, I must have looked like a caveman holding a Rubik’s cube as I swiveled my head from the rifle to the pellets and back to the rifle again. Okay, forget the gun idea.

I ran outside again, and figured I’d stand by the chickens until the hawk left the premises. I walked over to Chastity’s body, still motionless, sandwiched between Ruth and Patience who both looked frantic.

Oh poor Chastity. I remembered the time when—in this very spot—she launched herself at a invading groundhog, bravely throwing her beak into its ass like a mining pick. This garden, I thought, will seem awfully empty with just two chickens.

And just as I went to pick Chastity’s body up to bury her, she flung her head up and twisted her neck to see me. I looked over her body, and couldn’t find even a scratch.

As each chicken has developed and displayed their personalities, they’re no longer just barnyard animals who give us eggs every morning, they’re members of the family.

That night, I put them up in their coops early, brought them out a bucketful of leftovers, and packed their nests with fresh hay. And while they are now a little wary about being out in the open, they still spend their days pecking, scratching, and cooing, living as happy as three chickens can possibly live.

Ken Ilgunas’ blog is at SpartanStudent.blogspot.com.

More shiitake mushroom logs

Ken has finished a second batch of shiitake mushroom logs. This time, we used oak, plus a couple of locust logs as an experiment.

The first batch of logs have not yet shown any sign of production. It’s too early — five months. But we did the work in August, which is the least favorable time of year to start mushroom logs. Still, we have high hopes that that first batch of logs (all poplar) will make mushrooms.

The shiitake mushroom spawn, by the way, were mail-ordered from Oyster Creek Mushroom Company in Maine.

Ken shot video while he was making the new logs. He plans to post a how-to video of the process on his blog as soon as he has a chance to do the editing. Also, here’s a link to the photo series on the mushroom work Ken did in August.