A southbound Norfolk and Southern train approaches Pine Hall, North Carolina. I caught this train unexpectedly while giving the campaign manager for a state senate candidate an environmental tour of the Walnut Cove area. The train is about two miles north of Duke Energy’s Belews Creek Steam Station. Click here for high-resolution version.

Month: March 2018

Railway project #2

Using Google Earth’s satellite images, I followed the Norfolk Southern train route from Belews Creek, North Carolina, northward into Virginia, looking for photogenic spots. In the satellite images, I saw a trestle bridge just south of Ferrum, Virginia. That’s about an hour-and-a-half drive north from the abbey, if you take the backroads.

I would have to say that the drive was somewhat depressing. I had expected the backroads to be a picturesque mixture of hills, forest, and farmland. But because my route kept fairly close to the railway, what I saw instead was mostly decayed industry and the falling-apart old houses of the people who worked in those industries. Once upon a time, living near a railway meant jobs. Now it means unemployment, decayed infrastructure, poverty, and Trump voters. There were shockingly few farms. Apparently people didn’t farm much if they worked in the old industries. Instead, they worked for wages and bought most of their food in little country stores. There also were quite a few of what I call nasty little churches. They are independent churches, falling apart just like the houses, of fundamentalist denominations such as “Holiness.”

A county or two to the west of the railway, rural Virginia is much more beautiful. Now I know.

The trestle is just south of Ferrum on Prillaman Switch Road. The railway is following a ridge at that point. The trestle bridges a small stream. The stream was almost roaring with snowmelt on the March day that I was there. To get from stream level up to railway level required climbing a steep and rather treacherous bank. I climbed the bank with my digital camera, but the film camera and its tripod are just too heavy for such a climb. These are all digital photos.

At some point I’m going to time these expeditions to catch a coal train on the tracks.

Episcopic illumination

Two years ago, I wrote a post, with photos, about my Nikon Model S microscope. People who are Googling for this classic microscope often find my post, and it has been quite popular. In 2016, I did not have an “episcopic illuminator” for the microscope. I recently bought one on eBay. These devices for Model S microscopes seem to be fairly rare and don’t come up for sale often — at least not at a decent price.

An episcopic illuminator is a device that lights the specimen from above. What you see in the microscope is light reflected from the specimen. The opposite of this is “diascopic” illumination. In diascopic illumination, the light is below the specimen. What you see in the microscope is light that is transmitted through the specimen.

As you might imagine, both types of illumination are sometimes used together.

Somehow, my Nikon D2X camera seems to have infected me with a fetish for optics. Like my Nikon D2X camera, the Nikon Model S microscopes are now considered largely obsolete by professionals. But collectors and hobbyists snap them up for their quality and their continuing usefulness.

Unfortunately, the through-the-microscope photos here are of poor quality, because they were shot with an iPhone held over the microscope’s eyepiece.

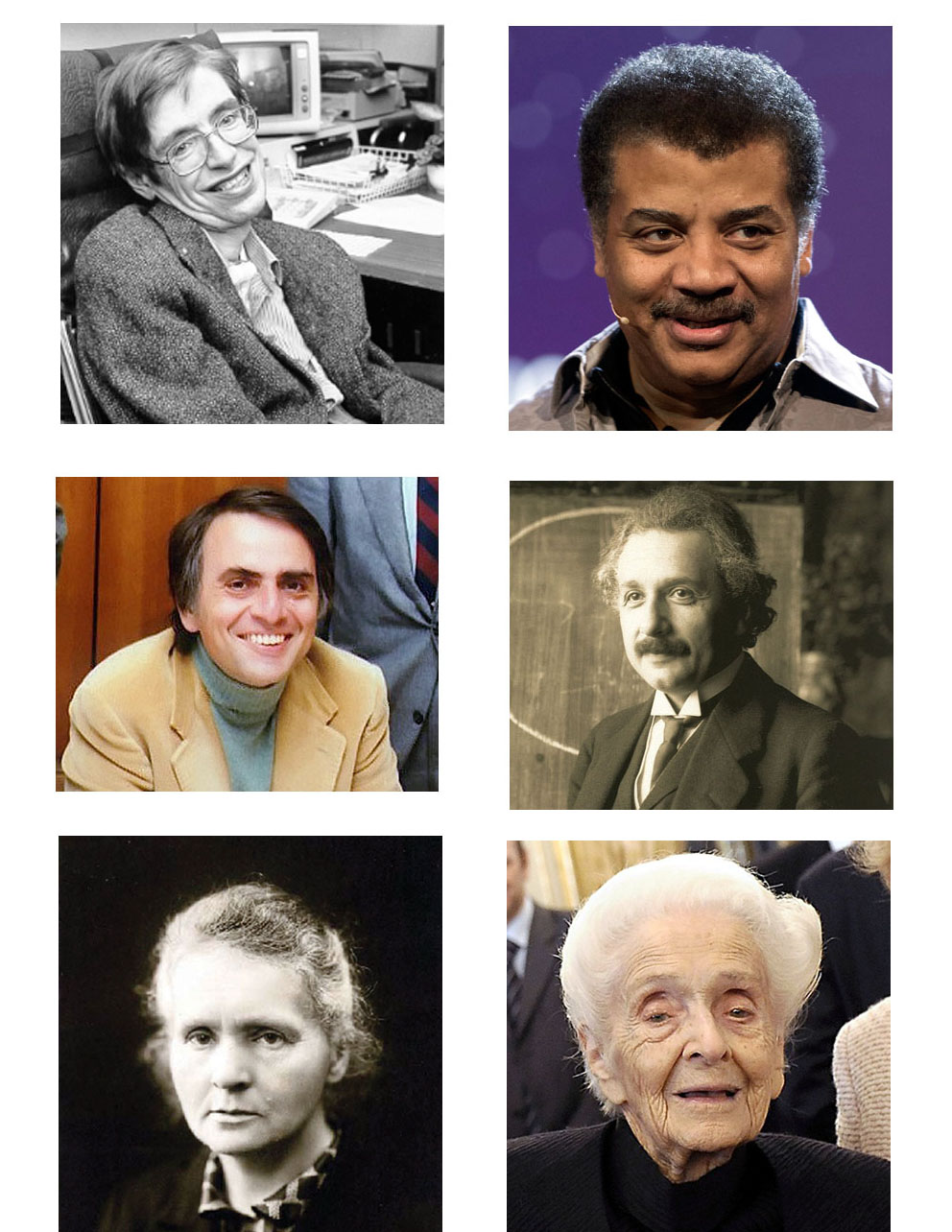

Celebrity scientists

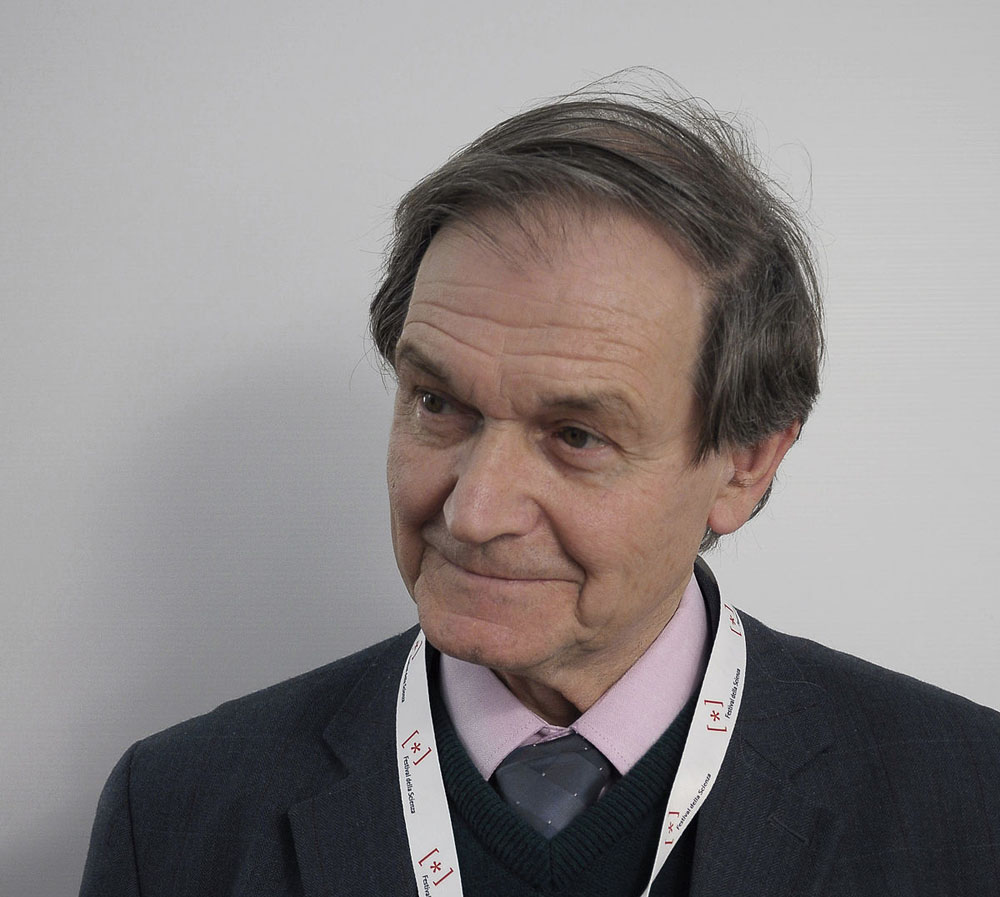

One of the healthier elements of our culture, including our media culture, is that we still have celebrity scientists. After the death this week of Stephen Hawking, we are left with a vacuum. To help fill that vacuum, I nominate Roger Penrose.

What are the characteristics that help elevate a scientist to celebrity status? Certainly they need to have discovered something or explained something that captures the public imagination. It helps if their personal stories are intriguing. It also helps if they’re charming and photogenic.

If you read this blog, you’re probably a serious reader. But do you read science? Much of my nonfiction reading is science, particularly physics. If you’re not reading science, then you’re missing a lot of the good stuff about what makes our times so interesting. Despite the steady progress in technology, and despite rapid progress in some of the sciences, physics is stuck and has been stuck for nearly a hundred years. That’s a big deal. It’s also a serious problem. But that doesn’t make physics boring. To the contrary, there is a growing suspense and sense of drama in physics as scientists struggle to unify relativity with quantum theory. Those two theories have been proven valid again and again. And yet they contradict each other in exceedingly mysterious ways. We still have no idea what gravity is — or time, for that matter — though there is tantalizing evidence that, when we finally do have a grand unification theory, an understanding of gravity will come along with it.

I have often said that I would like to live long enough to see two things — the grand unification theory, and the day the extraterrestrials land. I also am seriously open to the possibility that a grand unification theory will reveal that there is simply nothing here, nothing physical anyway, and that that is what has made the investigation so hard. Don’t laugh! Remember that Einstein warned us that we won’t get anywhere without imagination.

Why do I nominate Roger Penrose? I think I won’t even try to explain it, except to say that Penrose tries to tie the mystery of consciousness to the elusive grand unification theory. That’s not a mystical proposition. If you know about the “Schrödinger’s cat” thought experiment, then you know that observation by a conscious observer does seem to have something to do with the missing pieces of a grand unification theory, not to mention the mystery of something vs. nothing, or at the very least the mystery of something vs. bewildering uncertainty. I believe that Penrose is the Einstein of our time, the smartest person alive. You can find his books at Amazon. There also are many Penrose lectures on YouTube.

Science is a healthy antidote to the increasing primitiveness of our media and political culture. To read science is to strike a blow against the Republicans and religionists who are working to roll back the Enlightenment and turn off any lights that aren’t powered by coal. Next time you’re in a bookstore, why not check out the science section? Just pick a book on a subject that interests you. One subject always leads to another.

More about barley

Click here for high-resolution version

Back in January, when I wrote a post about fried barley polenta, I was using organic pearled barley, because that’s what I had at the time. However, pearled barley (though it’s very good) is not really a whole-grain product. Hulled barley is. Today, while it was snowing outside, I did another experiment with barley polenta using organic hulled barley. You can buy organic hulled barley in bulk at Whole Foods. It’s one of the best bargains in the Whole Foods bulk section.

There’s something magical about barley. It sticks to the ribs like nothing else. It’s outrageously healthy, both for the digestive system and for the bloodstream. It’s one of those foods that is pure medicine. No wonder the gladiators ate it. Smart people would figure out a way to make it a staple, using much more barley and much less wheat. The most delicious way to use barley that I’ve figured out so far is to make polenta from barley grits. Once you’ve figured out your method for cracking the barley into grits and working it into polenta, the next step is figuring out ways to season it. I plan to spin it as sausage when it’s served at breakfast (using sage and pepper). And it works great as a binder for vegetable burgers when served at supper. I’m guessing that it also would make a fine raisin pudding. It loves sauces, including gravy. It would make excellent arancini or risotto. It would substitute for meatballs in lots of recipes. It could be combined with soybeans and appropriate seasonings to make a vegan meatloaf. The barley experiments will continue.

Click here for high-resolution version

The photos in this post are digital, using natural light from north-facing windows.

Tinctures, on film

A friend in Black Mountain is experimenting with making tinctures. The alcohol is organic grape alcohol. The ingredients include all sorts of herbs and flowers. Also, below is the film version of the recent daffodils shot.

These are both film shots using Fuji Velvia 100 reversal film in the Mamiya RB67. The tinctures shot is with a 90mm K/L lens; the daffodils shot is a 250mm K/L lens. The tinctures shot is at f/32 with an exposure time of 45 seconds.

Where have all the fairies gone?

The Enchanted Forest, John Anster Christian Fitzgerald, 1819-1906

Where have all the fairies gone?

We could ask this question two different ways, depending on how you see the world. If you believe that fairies exist (or used to exist), then the question is literal. If you don’t believe in fairies, then there is still a serious question here, a cultural question. Why were fairies once such an important part of human lore? When did we lose interest in fairies? Why?

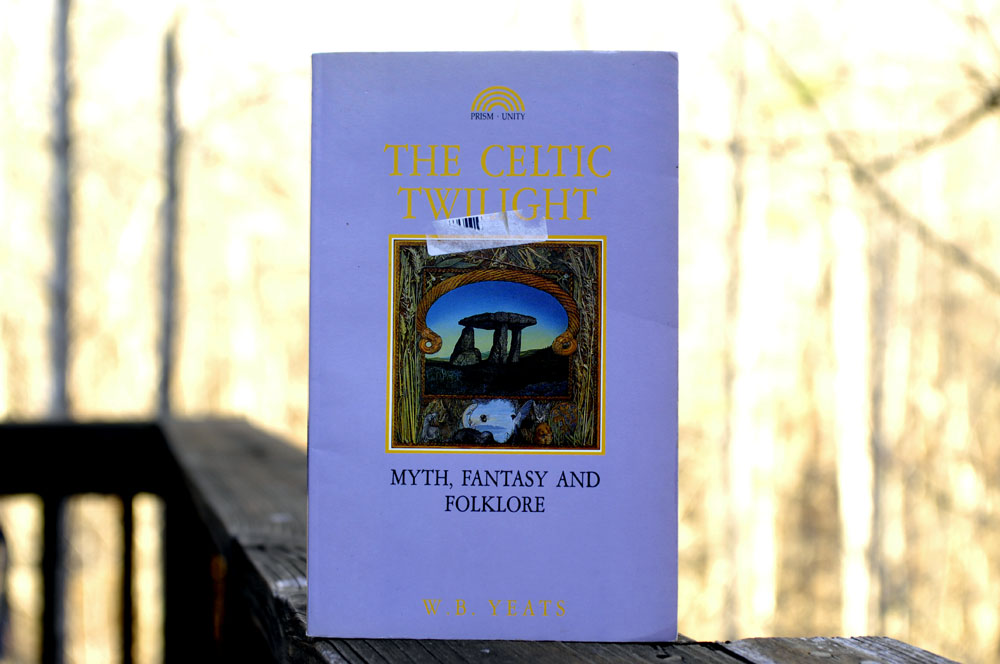

A friend who lives in France and who knows about (and shares) my interest in the Celts recently sent me a book, The Celtic Twilight, by the Irish poet W.B. Yeats. The book was first published in 1893. Yeats was a mystic, and I’m pretty sure he believed in fairies — or at least very much wanted to. In this book, he travels in rural Ireland and asks people to tell him what they know about fairies. Faeries were already fading then. But they were still very much a part of rural life and the Irish belief system.

I am certainly not the only person to wonder where the fairies have gone. I Googled for the words “where have all the fairies gone” and got a number of little articles. Most are like this. Those articles use words such as “spirit,” “vibration,” “devic,” and “plane.” Though it is harmless, this type of credulous, too-magical thinking makes me cringe. But I also found this, a much smarter and more thoughtful piece. The author thinks that we reached peak fairy around 1926. He thinks that it was the automobile that ruined the world for fairies. This is not just because cars are noisy and are made of metal (fairies hate iron), but because we stopped walking. In particular, we stopped walking in quiet places where nature is still unspoiled.

Though it’s bad manners to quote authors’ last paragraphs, I’ll make an exception here, because I think it’s important: “So, I’m pretty sure cars killed off the fairies and reduced the trove of local stories. And I’m also pretty sure of this: these could be revived if only we got out and about by foot more often, especially where the pavement ends.”

Rational as the author is, clearly he wants the fairies back. I do, too.

Often I stand in my upstairs windows, which face into the woods, downhill toward a little stream. Many times from those windows I have seen the white deer. I have seen an owl perched in the huge old beech tree that overhangs the big rock. The owl flew away on enormous wings when it saw me watching. The white deer, I believe, sleeps under the big rock sometimes. I have seen the trees crowded with hundreds of crows. The crows increasingly seem to like those woods — a positive sign, I think, of something. Noisy as the crows are (they come almost every day), I love the sound they make. The crows also nest in the woods. During the spring I watch them gliding in and out to their nests through holes in the heavy green canopy. One year, a mama fox raised two cubs in those woods. Out of the woods come squirrels, who sometimes get onto the roof of the house, and possums, for whom I leave snacks on the deck. In the spring, the bottom of the little valley is densely strewn with May apples. After a heavy rain, the stream almost roars as the water cascades over the rocks. The water, which at times has been cloudy, is remarkably clear and clean at present. These upstairs windows face west. The full moon sets in the woods, early in the morning. The wind in the trees sounds very different in the winter than in the summer. But particularly in the summer, the wind in the leaves sounds remarkably like the sea. The woods go on and on for miles. You’d have to cross some roads, but I’m pretty sure that one could walk all the way to Quebec from here, up the spine of the Appalachian Mountains, without really leaving the woods.

And so, reading W.B. Yeats’ carefully curated fairy stories from the 19th Century, I ask myself: Shouldn’t there be fairies in those woods? Should I hide the cars up the hill? Would I have to squint and look for them out of the edges of my eyes? Should I try taking naps on the big rock, under the beech tree? Would I have to eat some mushrooms? What sort of fairies might they be? Would they like me? Should I post a little sign, “Fairies welcome here”?

But seriously, the cultural loss is devastating. The 19th Century Irish country people whom Yeats interviewed about fairies were nominally Catholic, but I get the strong impression that Catholicism was a very weak force compared with the ancient folk beliefs. Priests were to be made fun of, but you’d better listen to what the fairies say. Whereas, if I hiked to the north and interviewed some neighbors, they’d know plenty of church talk, but they’d be utterly empty of imagination. And how many of them still walk in the woods?

There was a brilliant piece in last Sunday’s New York Times by E.O. Wilson, the biologist. He is arguing for the Half-Earth project, which he believes is necessary if the human species is to survive. The Half-Earth project calls for setting aside half of the earth as habitat for other species. Humans would keep to their own half, and in a sustainable way. That’s a brilliant idea. Maybe, then, there’d be room enough on earth for the fairies, too. Meanwhile I’ve got a little spot for them to help tide them over, if they’d like to have it.

If E.O. Wilson is right, and if we don’t make room for earth’s other creatures, then we’ll be next. It was just that the fairies went first.

Click here for high-resolution version

The fate of the caboose

Back in 2014, I posted photos of a caboose that was for sale. At the time the caboose was located in a private park near Madison, North Carolina. Last year, the town of Stuart, Virginia, bought the caboose and moved it to Stuart.

I’d have to say that I was pretty disappointed when I drove by to check out the caboose a few days ago. It’s now parked in a falling-apart old industrial neighborhood near the Mayo River. The caboose looks ill-at-ease and a little embarrassed to be where it is. The restoration work has been so-so. In fact, no work has been done on the interior at all.

The residents of the abbey actually briefly considered buying the caboose and renovating it as a B&B. The price of the caboose was reasonable, but the catch was the cost and hassle of moving it. Apparently the only effective way of moving something so heavy is with an industrial crane. So the cost of moving the caboose would have been greater than the cost of the caboose itself.

Still, I can’t help but think that the caboose would have been much happier here, tucked up into the woods above the orchard, nicely landscaped. There’s already water, electricity, and a septic tank connection at that spot, because that’s where I parked my camping trailer while I was building the house.

Oh well. Maybe a tiny house someday.

Let’s don’t dig the hole deeper

You’d think that radical centrists, whose perpetual wrongness is exceeded only by their perpetual smugness, would give up and go away. But their latest project is harassing the New York Times’ op-ed pages for “lack of opinion diversity.”

We liberals are said to live in a bubble, you see. We are regularly scolded for failing to “reach out” to Trump supporters. We are said not to understand Trump-supporter grievances and Trump-supporter views.

Here I need words for maximum contempt, maximum derision, and a healthy burst of anger. To say what I actually think would be too rude. But the truth of the matter is that I understand Trump supporters perfectly well. There is no need to “reach out” to them, because no bubble could possibly be good enough to prevent us from hearing all about what they think. We are fully immersed in it, even after we clean them out of our Facebook feeds. I know exactly what Republicans are going to say before they say anything. I know all their talking points. Name an issue, and I’ll tell you what Republicans think. And it’s 98.6 percent horsewash, an ugly mix of distortion, denial, fallacy, meanness, corrupt theology, and constantly repeated lies.

The idea, then, is that in the name of “opinion diversity,” the horsewash that saturates the right-wing media and that has warped the minds of about 40 percent of the population should also be allowed into the New York Times. It is alleged that this would somehow improve the minds and politics of we liberals who read the New York Times. It’s medicine we need that the Times ought to give us, an antidote to our lefty “partisan” views.

But this is exactly how we got to where we are today. When Fox News came along 25 years ago and learned how to make a profitable billionaire-owned business out of brainwashing ignorant old white people without a pot to piss in into becoming ever-angry foot soldiers for the billionaire agenda, the mainstream media were caught off guard. Often, those in the mainstream media knew a lie when they saw one, but to say that something was false and intentionally deceptive was not permitted on grounds of “balance.” And so, for 25 years, the mainstream media’s line was “opinions differ on whether the world is flat.” Thus the mainstream media was paralyzed and was unable to report, as a matter of plain fact, that Donald Trump is a corrupt and dangerous madman. Terrified of being accused of lack of balance, the mainstream media remained easily manipulable and thus actually wrote much more about Hillary Clinton’s emails than about Donald Trump’s criminal history and foreign entanglements. A media catastrophe enabled a political catastophe. Now we’re on course for a constitutional crisis and a catastrophe for the American democracy. And yet we’re told that we need yet more of what got us here.

The world is not flat. If an op-ed policy that refuses to coddle lies and distortion makes a bubble, then who would resent that bubble other than those who have lies to sell and those who enable them with their centrist apologetics?

Radical centrists see politics as inherently symmetrical. If there are irrational partisans on the right, then radical centrists assume that there must be equally irrational partisans on the left, in equal numbers. If partisans on the right lie and distort, then partisans on the left must equally lie and distort. Only centrists, they believe, can see things with objectivity and clarity and avoid partisan excess. Yes, there are those on the left who think that we have some sort of religious duty to “reach out” to Trump supporters. Let them alight from their Priuses and actually get some Trump-supporter spit in their faces, rather than sermonizing about it on Facebook, and see what they end up learning from those Trump supporters.

The right-wing media and right-wing politics have dug a very deep hole. With a still-unknown amount of foreign help, we have all fallen into that hole. “Opinion diversity,” which really means tolerating lies and disguised agendas, is not going to get us out. It’s how we dig the hole deeper.

Daffodils

Click here for high-resolution version

Flowers can be remarkably hard to photograph. The problem is holding the subtle range of color and texture in all the parts of the flower. A little bit of backlighting helps. And the exposure has to be just right.

This is a digital photo, but I’m about to shoot the same flowers with color film. Soon: fruit tree blossoms.