A little research suggests that bread books fall into two basic categories: Books for people who want good bread without investing a lot of time and trouble; and books for people who want the best possible bread no matter how much fuss or apparatus is involved. I’m in the second category. The first bread book I ever bought was James Beard’s Beard on Bread, the 1973 edition. Much has changed since then. Americans know a great deal more about good bread than they used to, so we have much higher expectations.

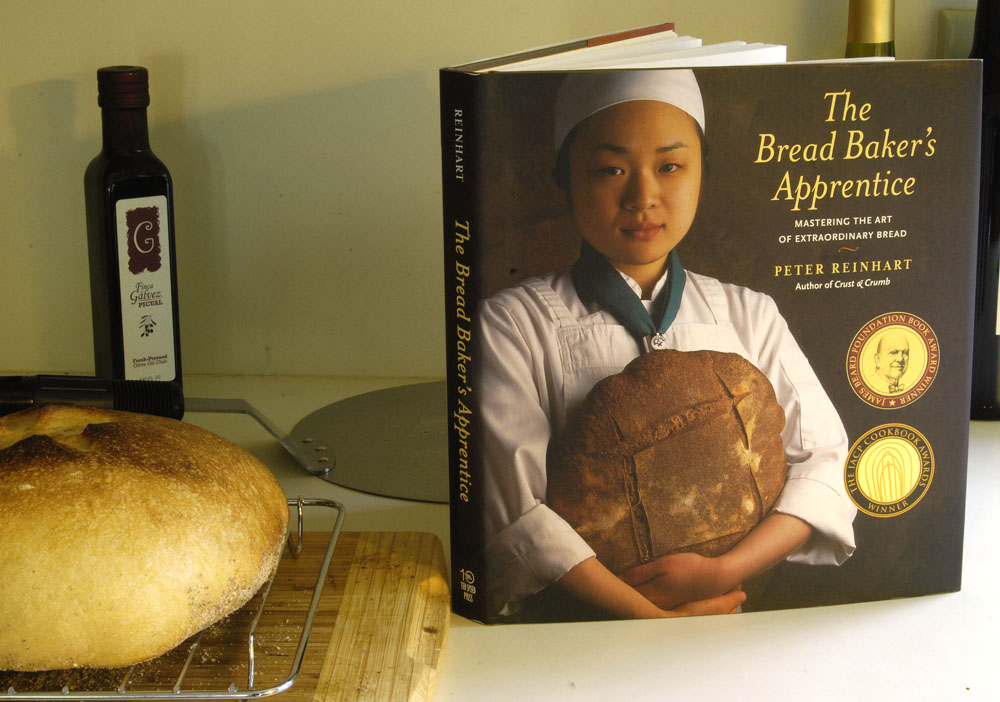

I shopped around for a book for those who aspire to artisan-quality bread. Peter Reinhart, author of The Bread Baker’s Apprentice, believes that 80 percent of the quality of bread is in the quality of the dough and that only 20 percent relates to the oven. I remain somewhat skeptical of that, because I doubt that Reinhart struggles very often with unsatisfactory ovens. But I do take his point — that making the dough is very, very important.

The first recipe I tried from the book was his basic sourdough recipe. I tend to not slavishly follow recipes, but in this case I thought I owed it to Reinhart to follow his recipe — he calls them “formulas” — as carefully as possible. Reinhart’s philosophy is that the fermentation process must be long and slow, so that biological and chemical processes can break down the starches and bring out the flavor. I am not going to argue with that. I have tended to rush breads, including sourdoughs. I won’t do that anymore, because Reinhart’s s-l-o-w sourdough was by far the best bread I have ever made. It may even have been the best bread that I have ever had, including in San Francisco and Paris. Both crust and crumb were superb, and the flavor was incredible. By the way, I have been using King Arthur organic unbleached flour (which is shockingly pricey but worth it), a sourdough starter that I ordered several months ago from Breadtopia, Celtic sea salt, and filtered well water. That’s it.

I think I have pretty much identified where my breadmaking skill needs to be improved to get to a really professional level. The new steam oven has solved a major problem. I’ve acquired a baking stone and a baker’s peel, which are necessary for hearth-baked breads such as sourdough. I think I’ve learned my lesson about rushing breads, and I won’t do that anymore. My remaining problems have to do with the final shaping of the loaf and getting the loaf, once it hits the oven and springs, to go upward rather than to sprawl. I’m getting better at creating the surface tension in the final dough shaping to make that happen. Steam is essential, or there won’t be much oven spring at all. And when you bake on a flat stone to get a good bottom crust, there’s no pan there to keep your loaf from spreading. But as for the taste of my sourdough bread and the quality of the crust and crumb, I’m happy.

Reinhart includes a thermometer in his list of essential equipment. I got one. For the sourdough bread, he suggests a final internal temperature of 200 to 210 degrees. No problem; 207 degrees is when bread looks done to me, but the thermometer certainly helps control the process. He likes proofing baskets but considers them optional. I’ve ordered some Banneton proofing baskets, and I hope they will help to get my loaves to push upward in the oven rather than to sprawl.

The diet scale has been in the closet. I’d better get it out and start watching my weight again.