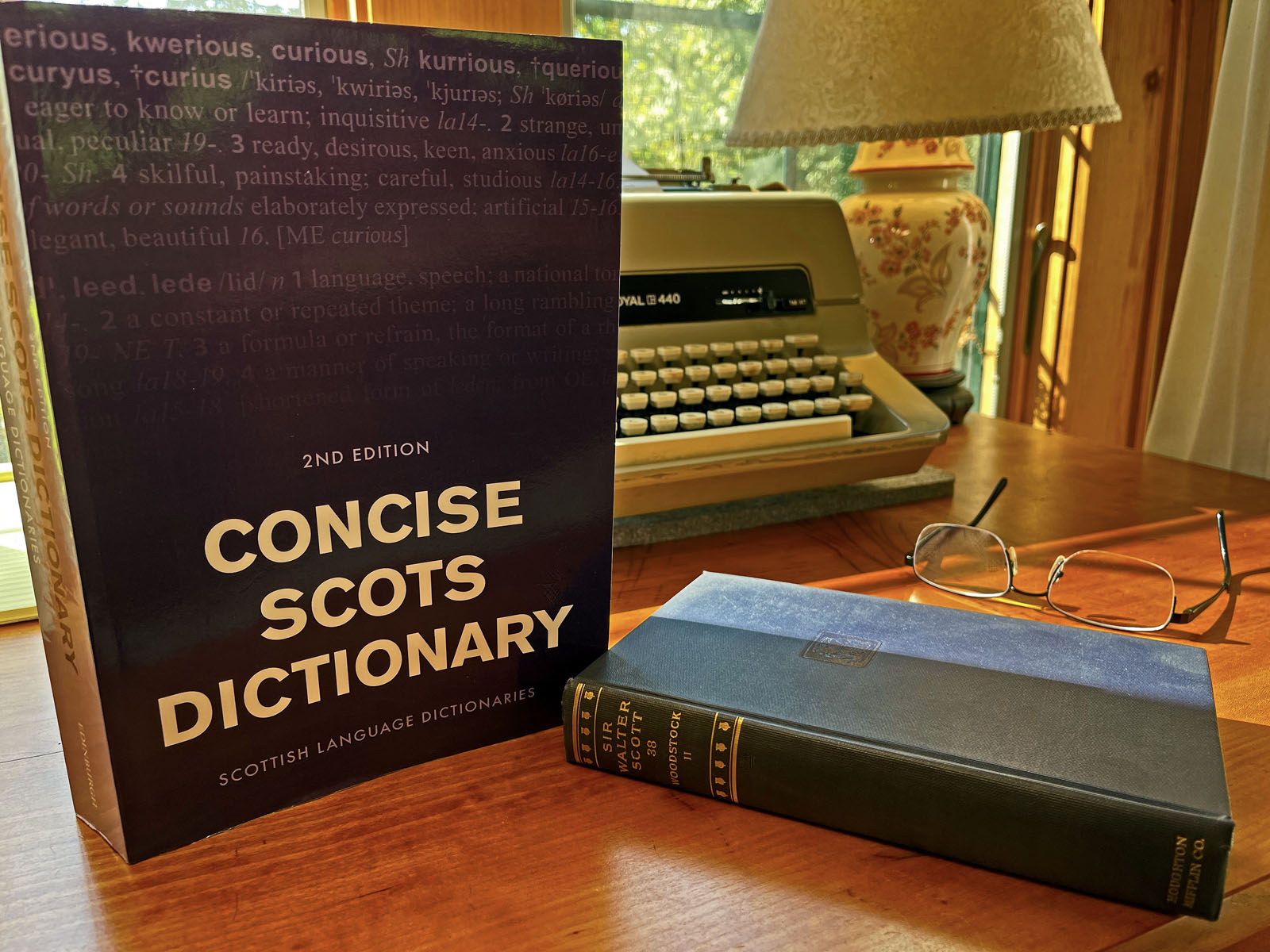

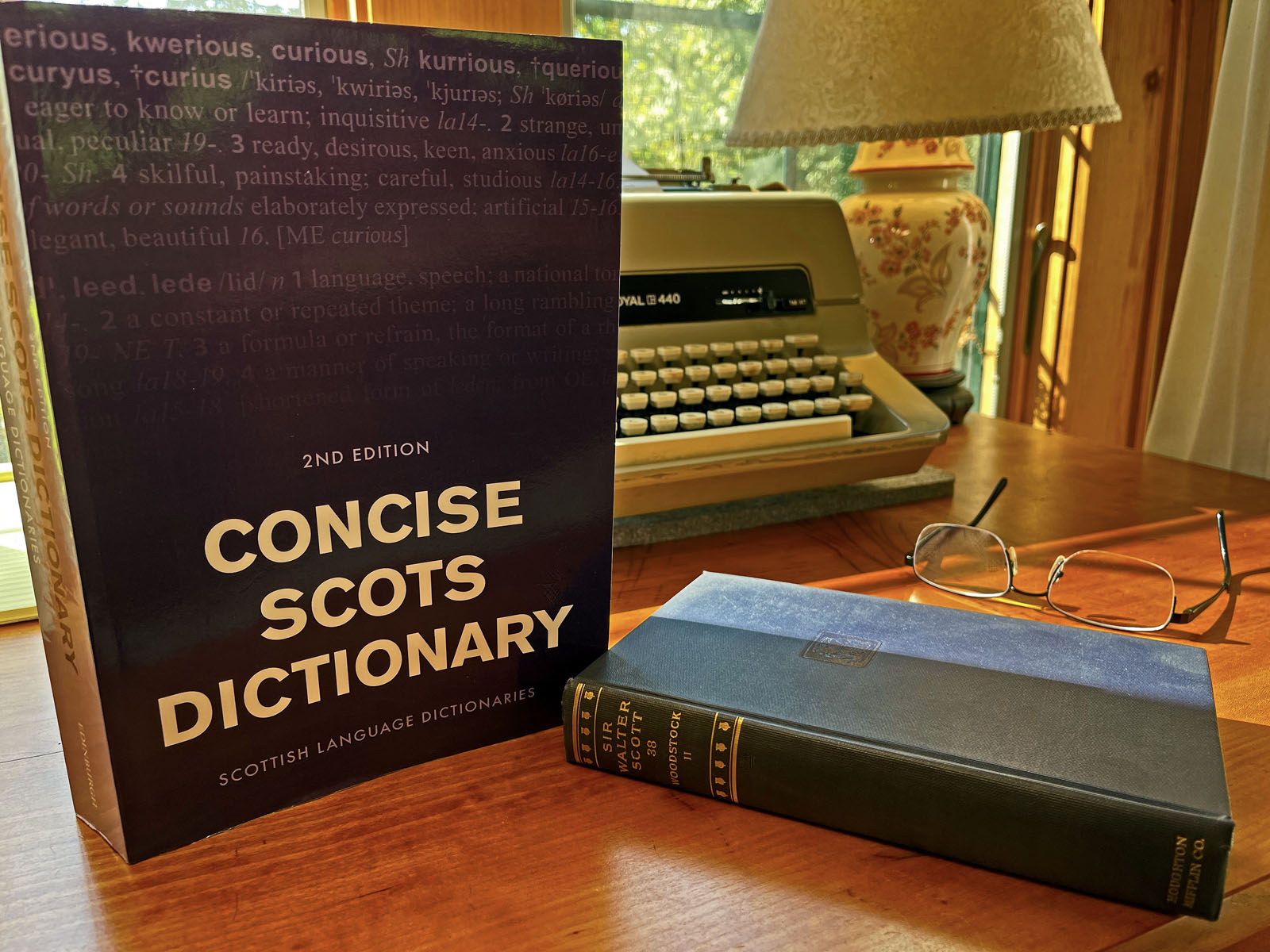

Concise Scots Dictionary. Edinburgh University Press, 2017. Second edition; first published 1985. 852 pages.

In the academic debate about whether Scots is a language or just a dialect, it had seemed more likely to me as a mere reader and non-academic that Scots is a dialect. This was only because I can understand it, or at least very largely understand it, both when I hear it spoken or when I read it as Sir Walter Scott represents it in his novels. But I believe I have changed my mind. It’s a very cool thought: What if we native speakers of English understand a second language that is a close relative of English? After all, we consider Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish to be different languages, though they understand each other. I have even seen this written as their being able to “make themselves understood,” as though the differences in the Scandinavian languages (about which I know nothing) are greater than I imagined them to be.

A friend of mine who speaks good French claims that, if French people speak French to Italians with an Italian accent, they’ll be understood. I thought that was funny. Now I’m convinced that it’s probably true, or at least partly or largely true. I don’t have any Italian, but after taking up French in middle age after years of Spanish in junior high, high school, and college, I came to realize just how similar the languages are. I’ve lost most of the Spanish, and I found that if I tried to speak Spanish, say, to the crew that framed my house, French came out. It’s an experiment I’ve never tried but would like to try. If I spoke the best French I can muster to a Spanish speaker, using Spanish pronunciation, would I be understood? I actually think that I could make myself understood, especially if I emphasized words that I know to be cognates.

This Scots dictionary includes an introduction with the title “The History of Scots.” This introduction takes the strong position that Scots is a language, not a dialect:

It may therefore reasonably be asked if there is any sense in which Scots is entitled to the designation of a language any more than any of the regional dialects of English in England. ¶ In reply one may point out that Scots possesses several attributes not shared by any regional English dialect. In its linguistic characteristics it is more strongly differentiated from Standard English than any English dialect. The dictionary which follows displays a far larger number of words, meanings of words and expressions not current in Standard English than any of the English dialects could muster, and many of its pronunciations are strikingly different from their Standard English equivalents. Moreover, the evidence of modern linguistic surveys is that the Scots vernacular is less open to attrition in favour of standard usages than are the English dialects. One illustration of this is the fact that a fair number of dialect words, such as aye always, pooch a pocket, shune shoes, een eyes, and nicht night — have very recently died out in northern England but remain in vigorous use in many parts of Scottish society. … But what most of all distinguishes Scots is its literature.”

Reading through this long dictionary also helped convince me that Scots is a language. A vast number of words are completely foreign to me, though probably most of those words would rarely come up in most conversations, words such as gleebrie for a small piece of sorry land.

Part of the pleasure of reading Sir Walter Scott is the language, both his archaic but colorful English as well as the Scots. I’ve made a project of reading Scott, so it seemed sensible to wrap that into acquiring a better feel for Scots, especially since I love Scotland so much.

There’s another reason I’m curious about Scots. Many of the settlers of the Appalachian Mountains were from Scotland, and thus one would expect Scots to have had a large input into the Southern Appalachian dialect, which I understand perfectly well having grown up with it. Though there are a good many commonalities — a mess of beans, or reench or ranch for rinse — most of the Scots words are completely strange to me. No doubt there has been much academic work on Scots and Southern Appalachian, and I need to look for that. But my guess would be that, even if Scots had less an effect on Southern Appalachian than I would have guessed, it’s probably true that someone who understands Southern Appalachian would have an easier time understanding Scots than, say, someone from California with their perfect standard American English.