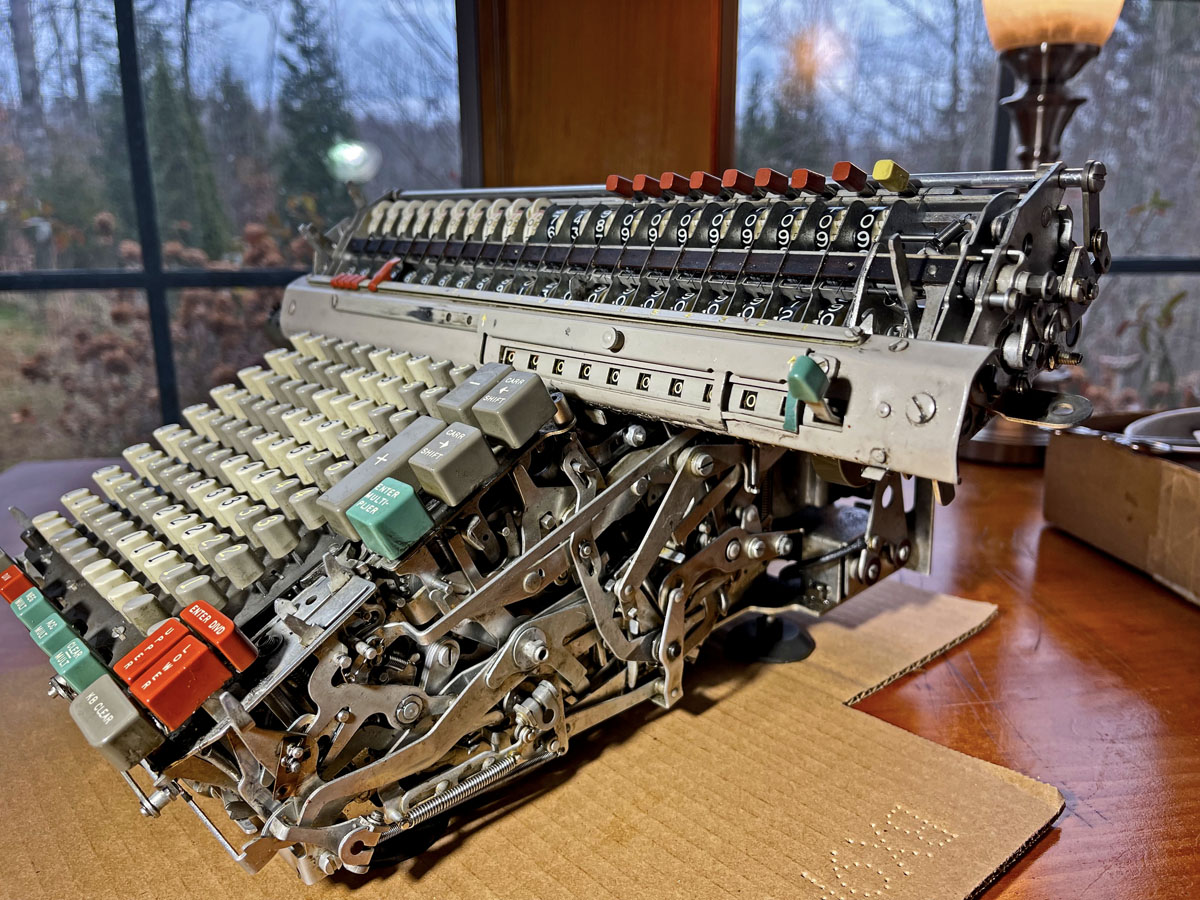

The eBay portrait of the machine I bought

With apologies to non-nerds, this is a nerd post.

I have written in the past about a quirk I have — empathy for mechanical things. Seeing a beautiful old machine (or any beautiful machine, for that matter) abused or falling into ruin is painful. Like abused or abandoned animals, old machines silently cry out to be rescued and given a forever home, and I hear them. There comes a time in the life of a machine when its value falls to near zero. Many go to landfills, or to crushing machines, at that point. And yet, if an old machine survives to a certain age in restorable condition, its value may start to rise. Think of “barn finds” of classic automobiles. Some barn finds, after being rescued and restored, are worth a fortune.

My particular weakness is for old machines that are complicated and that have a keyboard and a complicated set of controls. That is my favorite kind of toy. My brother, coincidentally, has the same syndrome but with a different twist. His weakness is for old machines with engines. He just bought a 1941 Aeronca airplane. My toys are far less expensive than his, though.

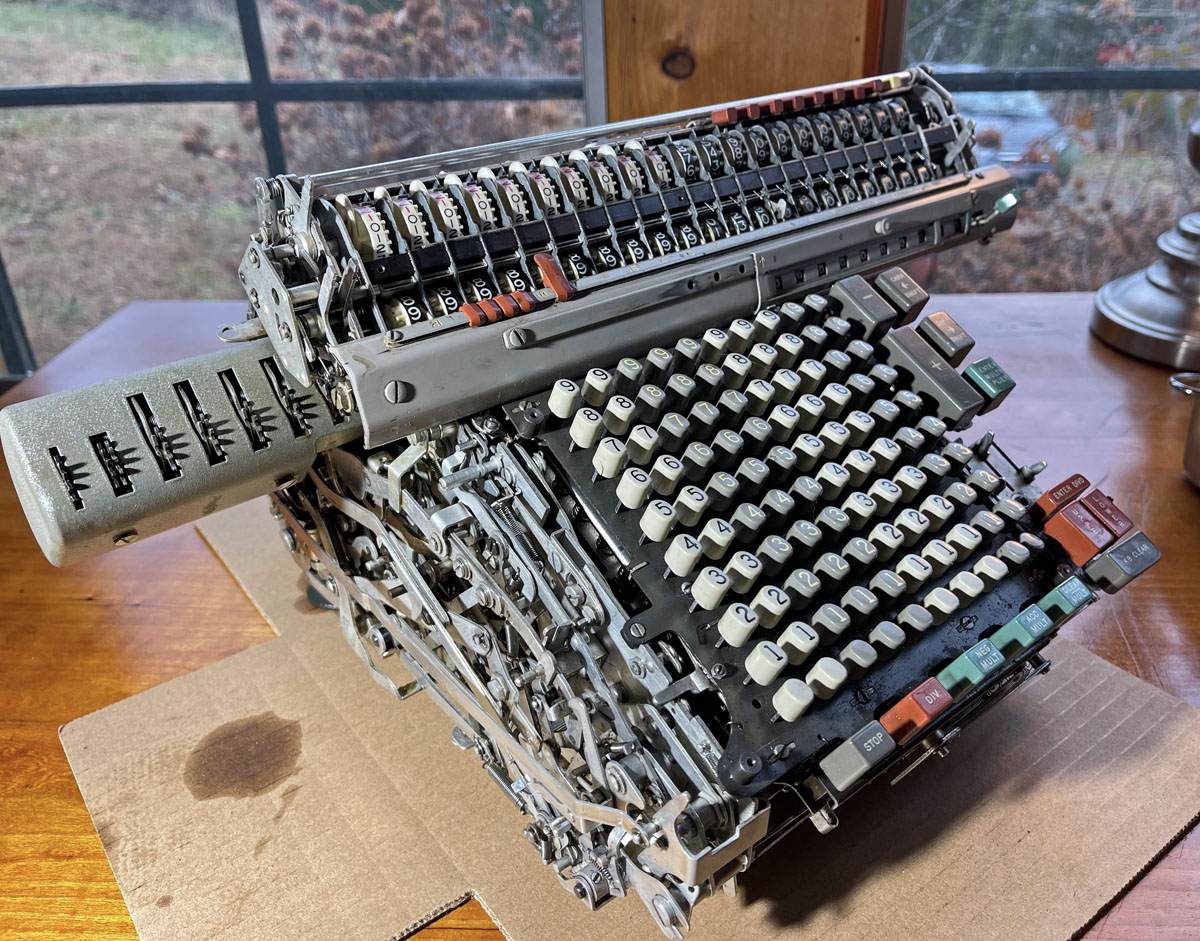

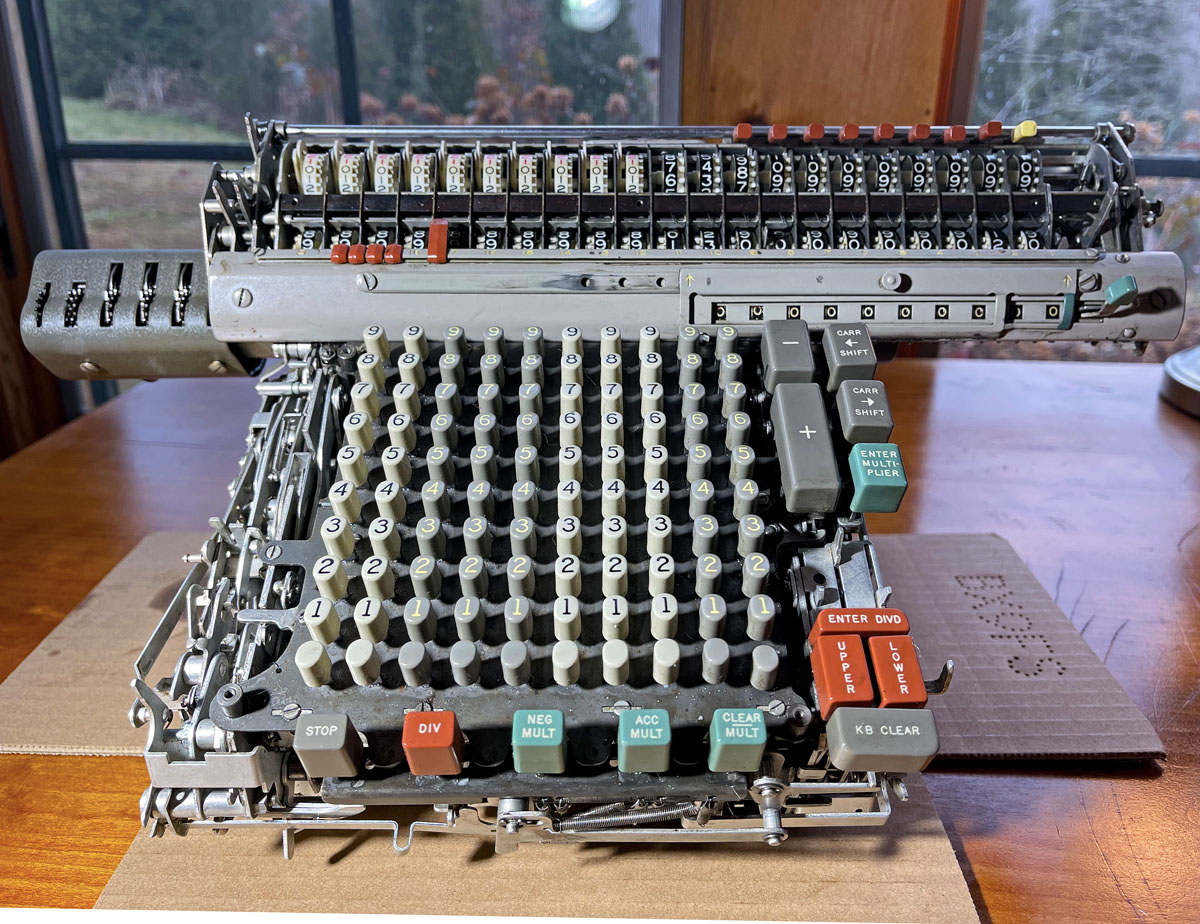

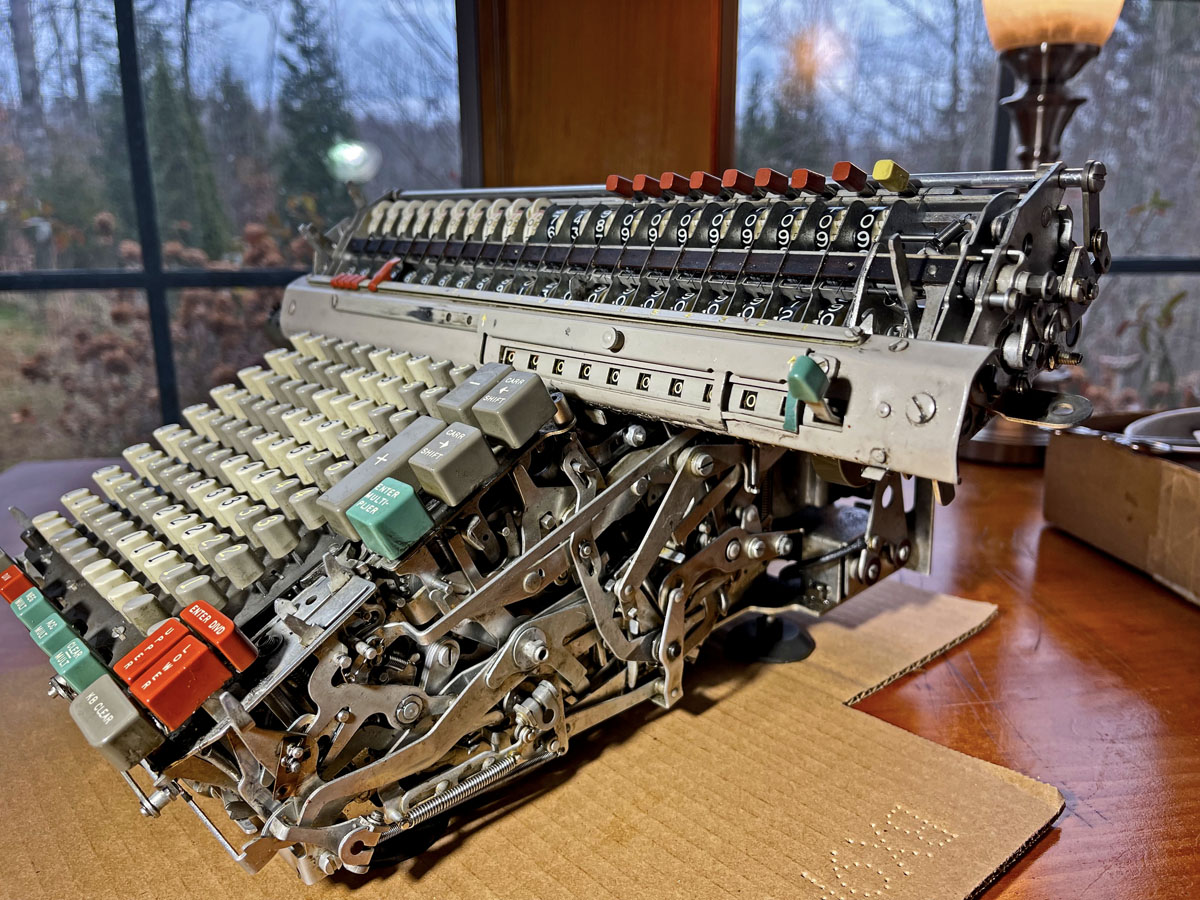

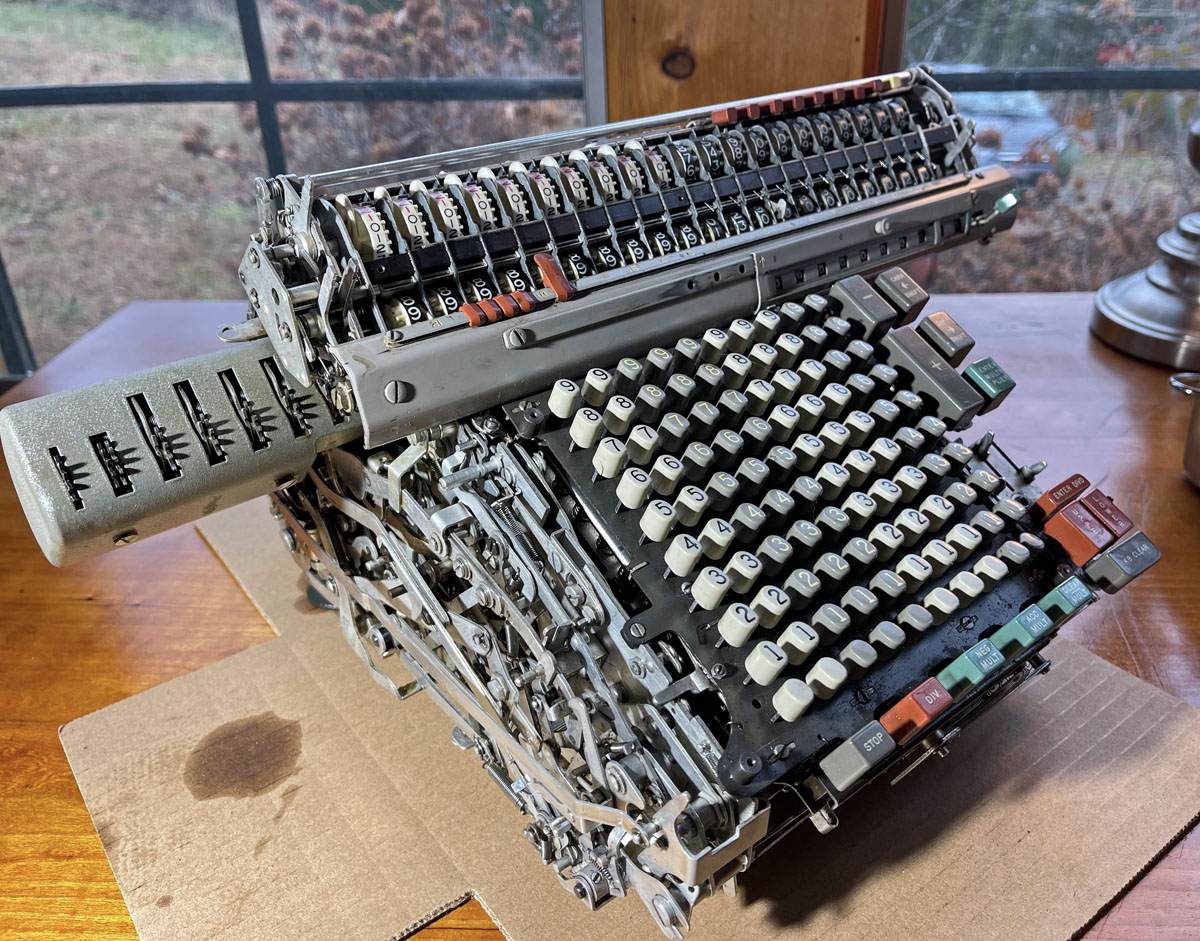

This Monroe 8N-213 electromechanical calculator cost me $125 on eBay (plus a hefty shipping charge). The eBay listing said that it made a noise when plugged in but that otherwise its condition was unknown. On the outside, the machine looked very good and showed no signs of abuse. It was a pretty safe assumption that the inside would be in good condition, too. The problem, though, is that even a machine that went into storage in working condition will soon stop working. All the lubricants dry out and become sticky. The moving parts all freeze up. The process of getting the machine back into working order is long and tedious. It involves cleaning up the residues of old lubricants, then using new oil and new grease to get everything moving again. Getting things moving again means exercising the machine. Not long ago I bought a Remington adding machine on eBay and got it working again, but that was a simple process compared with a machine as complicated as the Monroe 8N-213.

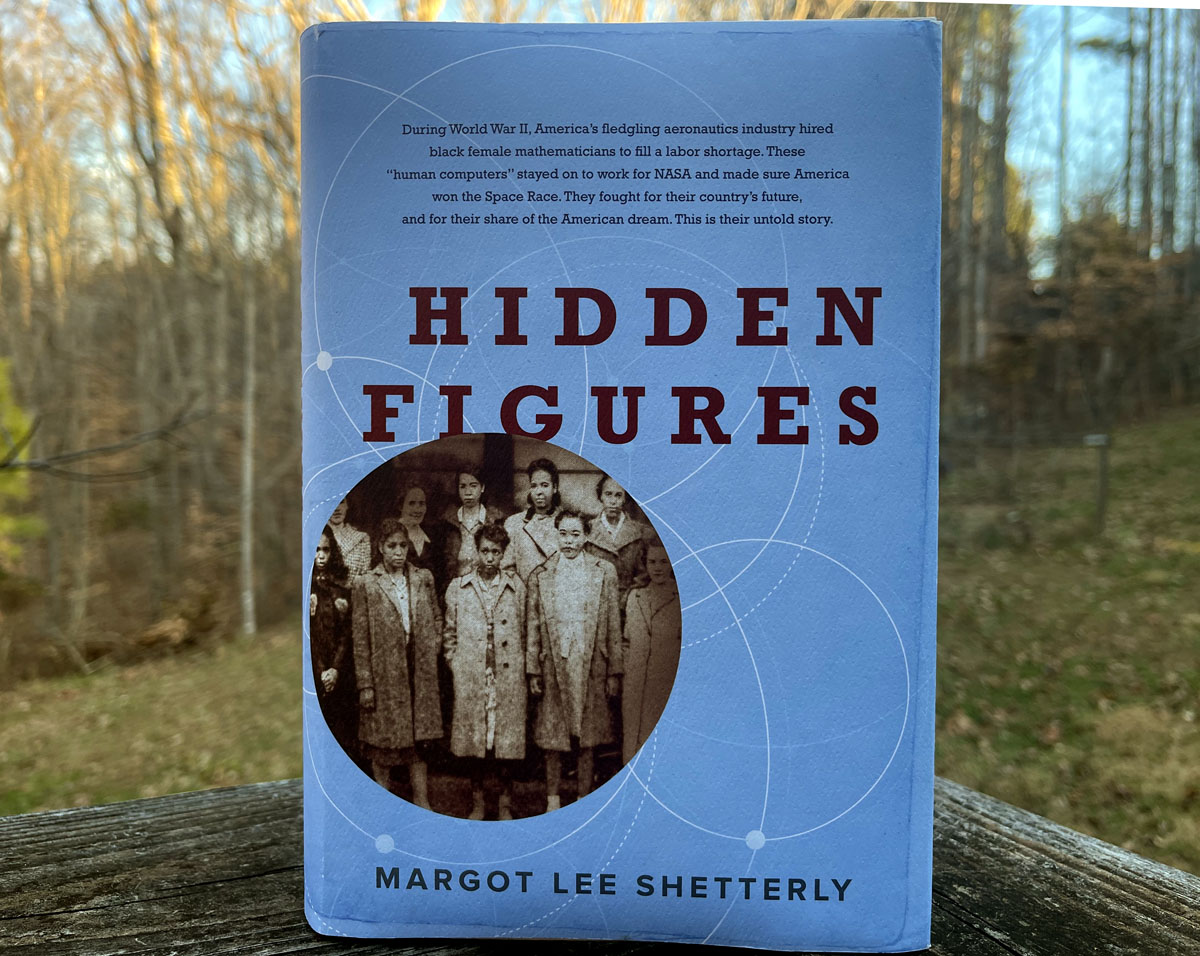

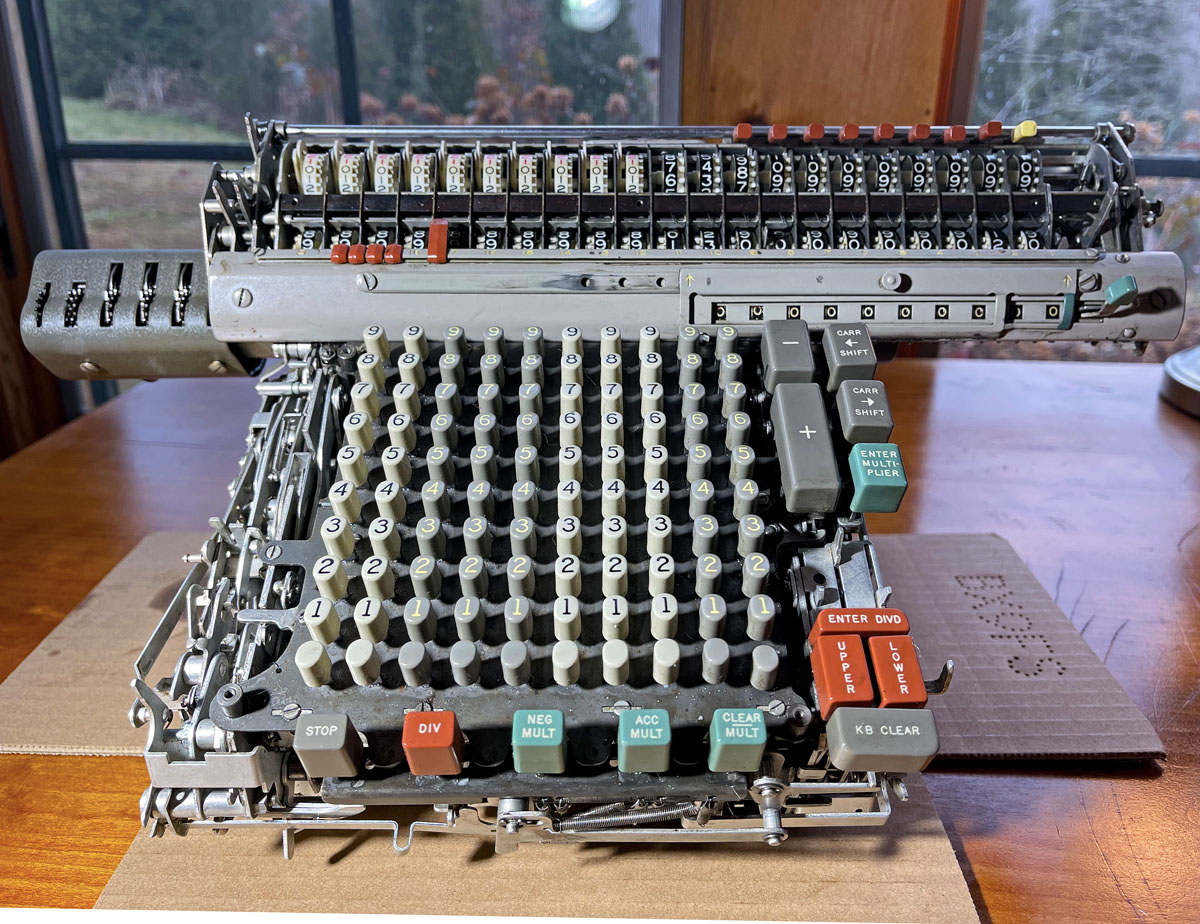

Part of the romance of the Monroe 8N-213 is that it was the type of machine used by Katherine Johnson, the mathematician who worked for NASA and the subject of the wonderful movie “Hidden Figures.” In “Hidden Figures,” a Friden STW10 calculator is shown on her desk as a prop. That is only partly historically accurate. It’s true that the Friden machine and the Monroe machine were contemporary and comparable. But Katherine Johnson preferred, and used, a Monroe. Restoring one of these machines, in a way, is a way to honor Katherine Johnson (and all the old NASA mathematicians and engineers). I hope her Monroe 8N-213 is in a museum somewhere, or maybe in the hands of her family, but I was unable to find out her machine’s fate. There are examples of this machine in the Smithsonian.

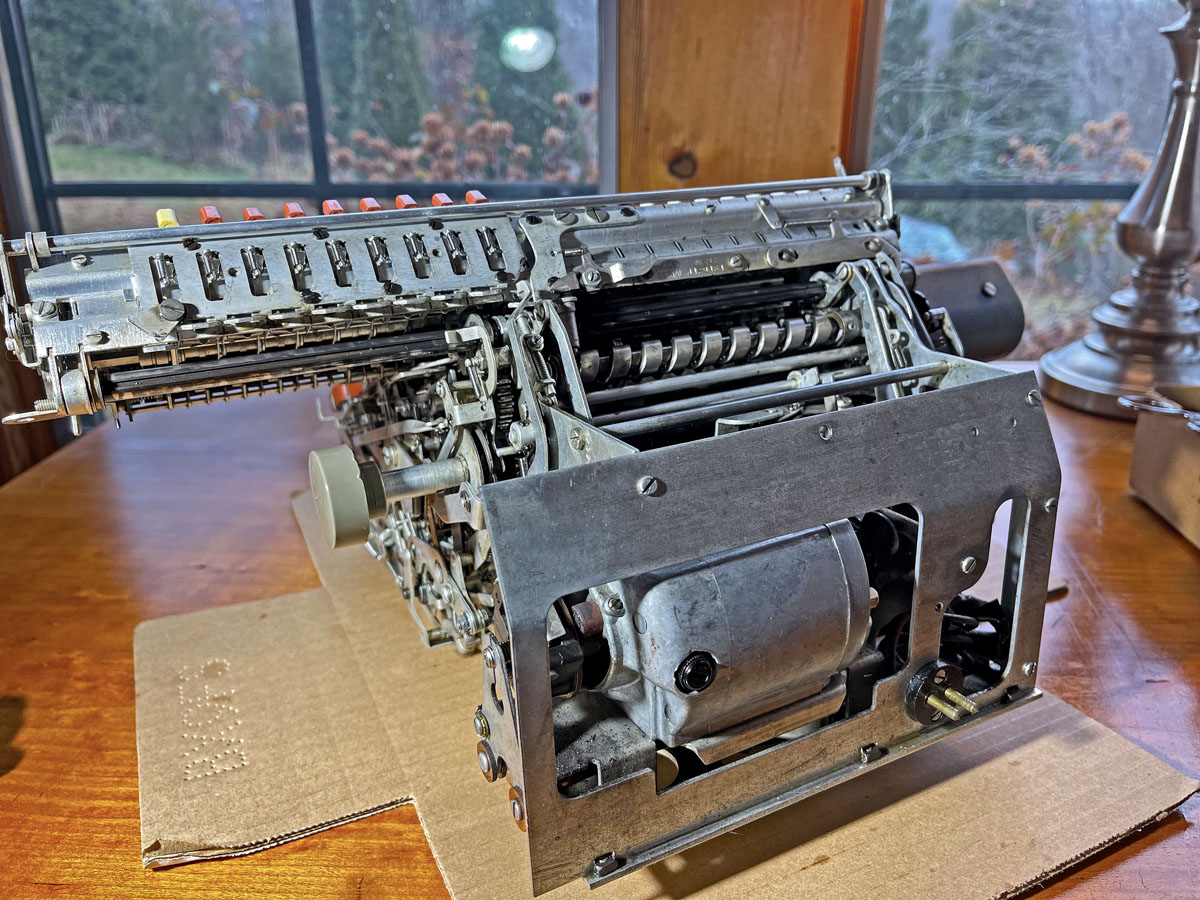

My Monroe machine surveyed the trip with UPS, though I was not greatly pleased at how the seller boxed it. When I plugged it in for the first time, the motor ran, but none of the keys worked. Everything was stuck — everything. After the generous application of a solvent (CRC 2-26 is my preference), it was fairly easy to get addition and subtraction working again. Multiplication and division, though, are much more complicated. That’s because, when dividing or multiplying, the machine’s carriage flies back and forth. An addition or subtraction takes only a fraction of a second. But multiplication and division may go on for quite a while. If you try to divide by zero, the machine will never stop (though the Monroe 8N-213 has a handy “stop” key for such situations).

At the moment my machine is stuck again. I made the mistake of attempting to do a division, because I had gotten the carriage moving again. I thought that doing a division might be good exercise for the carriage. But it stuck. It’s not possible to force the machine to come unstuck. That would cause damage. So I have to hope that continuing the process of de-gunking the machine will get the carriage moving again. Once I get things working (fingers crossed), I have two types of grease and two types of oil to apply to the thousands of moving parts. These machines don’t appear to wear out. Lack of use and dried-out lubrication is what disables them.

I estimate that my machine was made around 1956. Its cost then was just over a thousand dollars — about the cost of a new car at the time. Electromechanical calculators were built that were much more complicated (for example, the Mark I that IBM built for Harvard). But the Harvard machine was a one-off custom machine. As far as I know, the Monroe 8N-213 was pretty much the apex of mass-produced electromechanical calculators, just as the IBM Selectric III was the apex of typewriters (I have one, in excellent working condition). You can see a Monroe 8N-213 in operation here, on YouTube. It was computer chips and digital calculators, of course, that brought the era of mechanical calculators to an end.

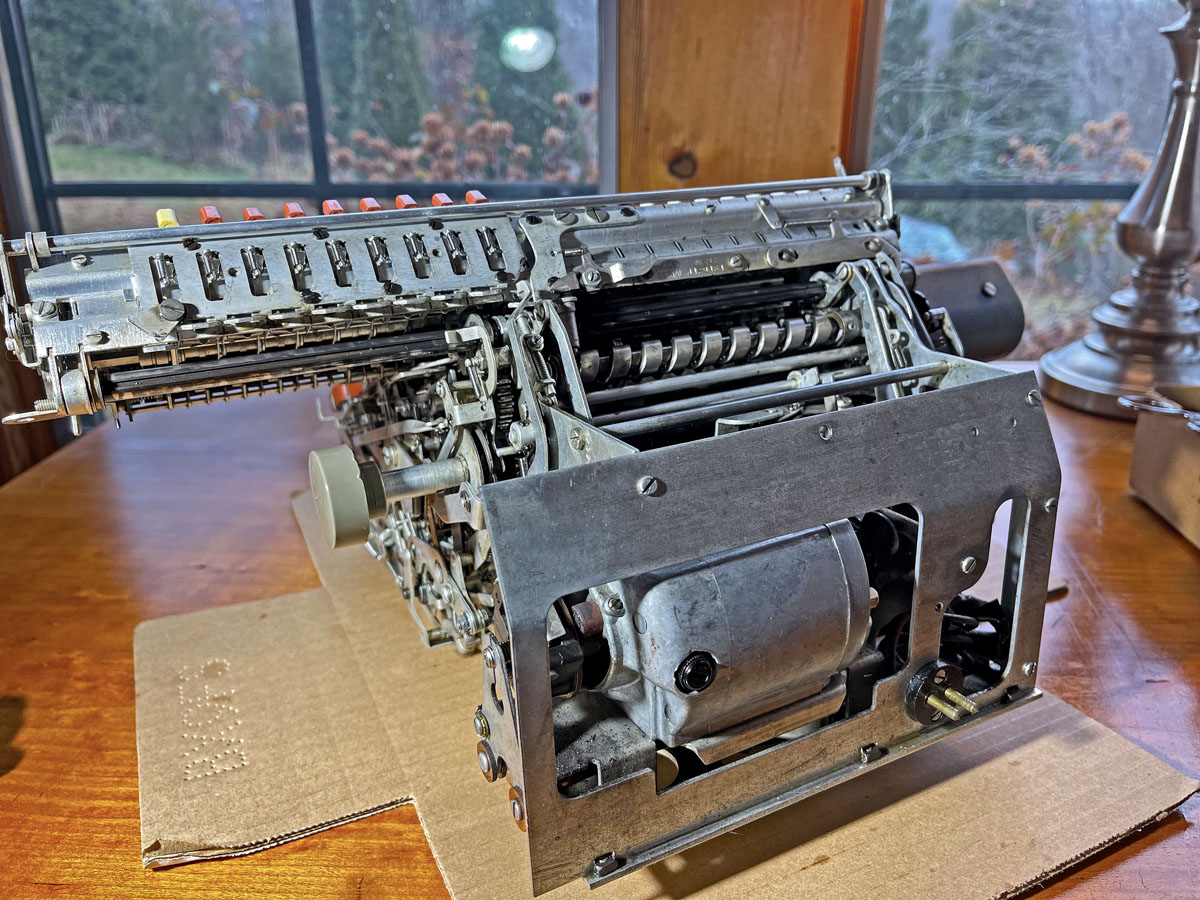

I’ve removed the case to work on the machine.

Katherine Johnson at her desk at NASA. That’s a Monroe 8N-213 in front of her. It is said that, when a computer helped with orbital calculations, she would check the computer’s work with her Monroe. NASA photo.