From JaneAnne’s bothy on the isle of Gometra, looking toward the isle of Ulva. Click here for high-resolution version.

Mull, Ulva, and Gometra, September 2018

To the regular readers of this blog: Blog posts often have a long life, as people Google for the terms and tags included in the post. Lots of people hike the Scottish isles, so partly this post is structured to be helpful to people who may be doing research for hiking in the Scottish isles.

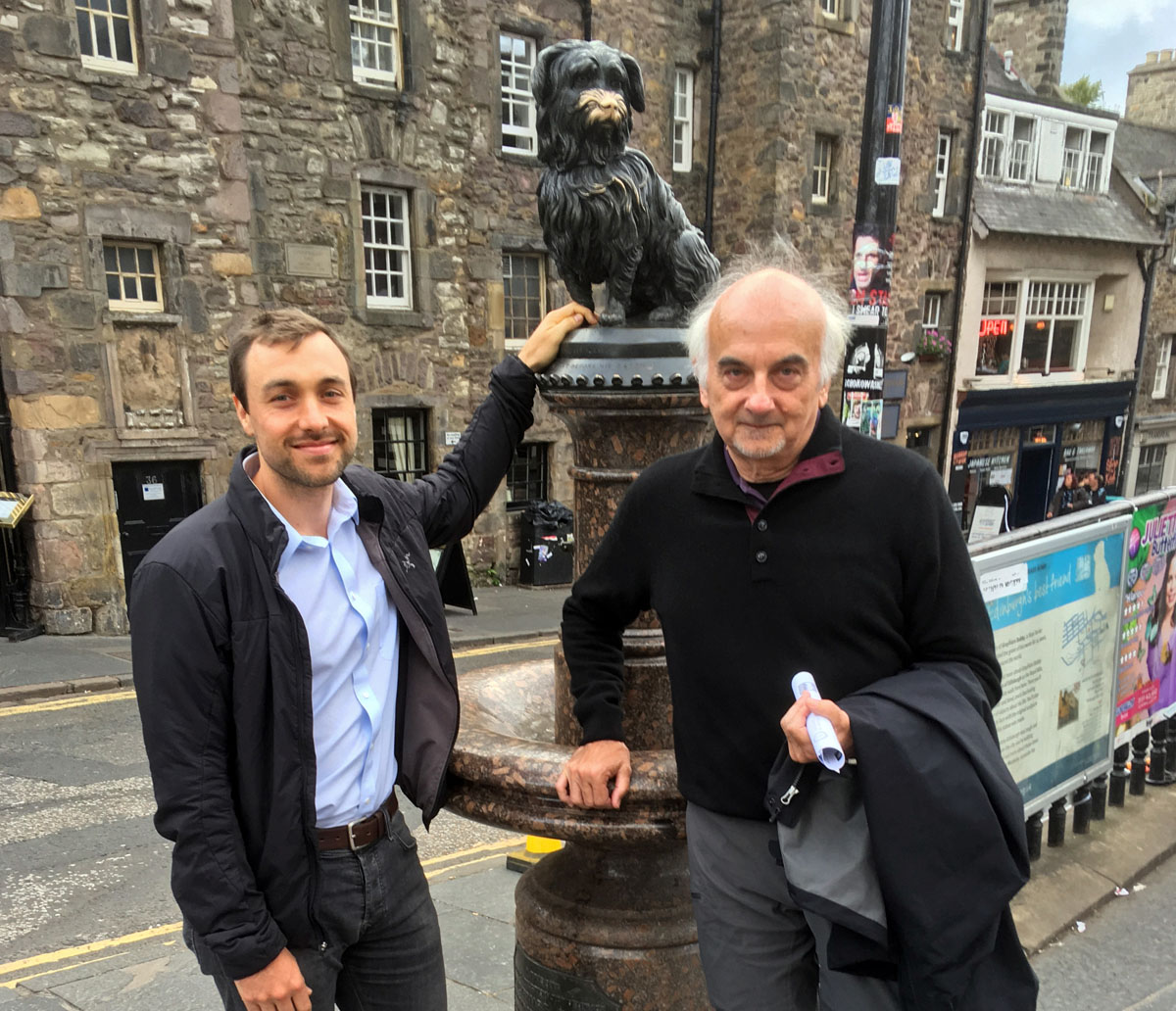

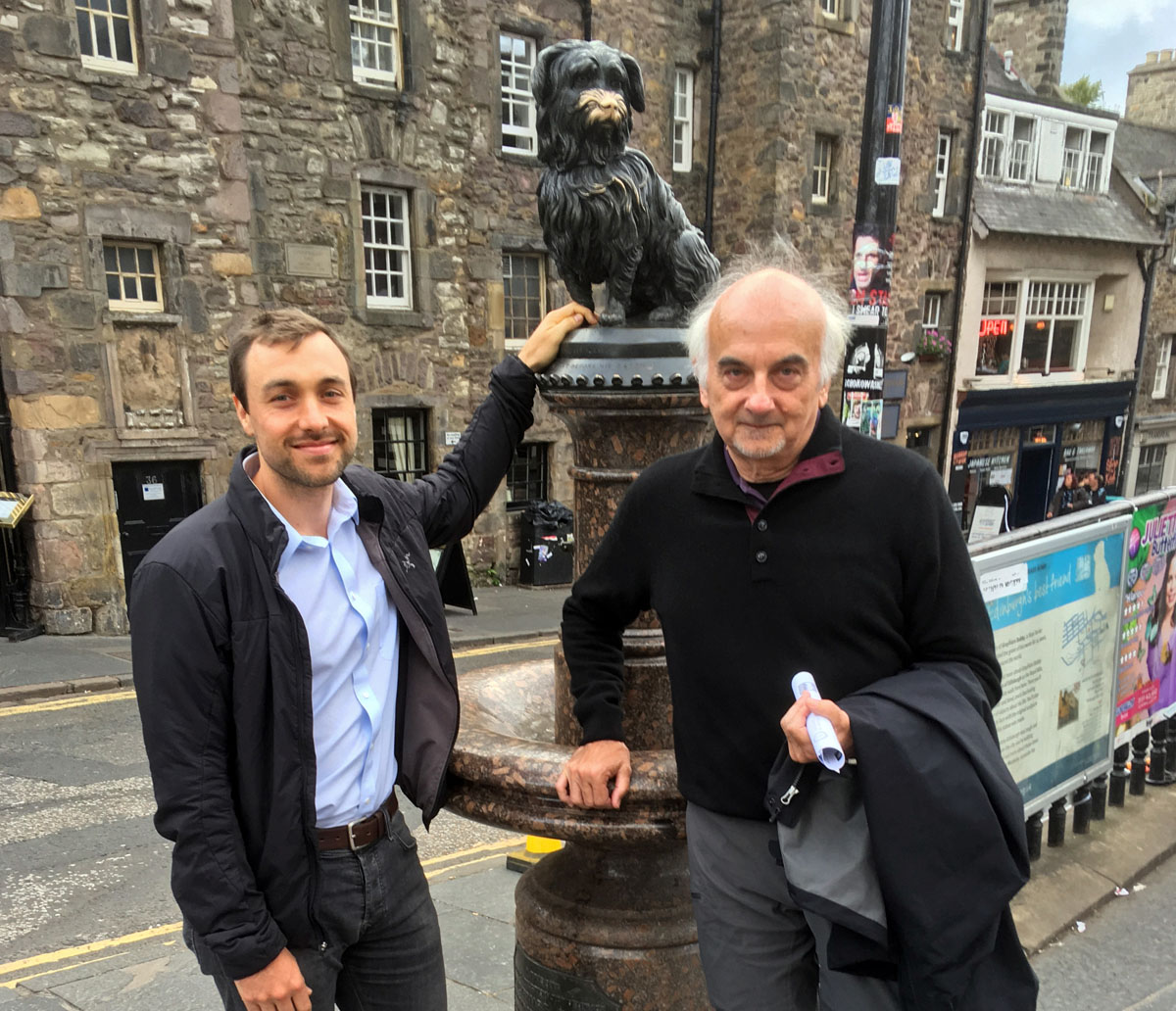

The hikers

Ken Ilgunas (left) and David Dalton in Edinburgh, September 2018. David is the author of this blog post.

For more than eight years, we have been literary confederates. But this was our first real hike together. Ken is the author of:

Walden on Wheels: On the Open Road From Debt to Freedom (2013)

Trespassing Across America: One Man’s Epic, Never-Done-Before (and Sort of Illegal) Hike Across the Heartland (2016)

This Land Is Our Land: How We Lost the Right to Roam and How to Take It Back (2018).

Ken’s small-press titles include:

The McCandless Mecca: A Pilgrimage to the Magic Bus of the Stampede Trail.

If there is such a thing as a professional hiker and adventurer, then Ken is one. David, two months away from his 70th birthday, trained all summer for the hike. David is the author of two science fiction novels:

Fugue in Ursa Major (2014)

Oratorio in Ursa Major (2016)

About the photos

Looking down toward Lochbuie from the eastern shoulder of Ben Buie. Click here for high-resolution version.

To prevent the page from loading too slowly, all the photos’ resolution has been reduced. For most of the photos, a link is provided to pull up the high-resolution version. The photos are by David unless they are tagged with Ken’s name.

Layers and layers of hauntedness

A ghost village left by the Clearances. The village is near Calgary on the isle of Mull. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Europeans are well aware of their long history on the land, though much of that history has been lost except to archeology. We Americans, on the other hand, are deeply impressed by the oldness. In places such as the Scottish isles, humans have occupied the land for so long that even the ruined castles are relatively new. In Oban, the day before we took the ferry to the isle of Mull, I found just the right reading material in a book store. That was Pagan Britain by Ronald Hutton. It’s an academic book published by Yale University Press. The author is a professor of history at the University of Bristol. The book is a detailed, no-nonsense, unromanticized study of what we know about the earliest inhabitants of the British Isles. Anatomically modern humans, Hutton says, were in northwestern Europe from about 42,000 B.C. From about 10,000 B.C. forward, the findings of archeologists are very rich. But the problem is interpreting those findings.

The prehistoric standing stones and barrows, of which there are a great many in Britain, present mysteries about our ancestors that we probably will never really understand. But in the case of a 15th Century castle, we know much, much more. More recently, in the Scottish isles, the 19th Century Highland Clearances are still a living memory. During the 18th and 19th Centuries, thousands of Highland families were cruelly forced off the land. The land was turned over to aristocrats, largely for sheep farming to feed the wool industry. The cultural loss was devastating. The Highlands have never really recovered from the depopulation, though efforts are now under way to repopulate some of the islands, including Ulva.

If you go for a long hike in Scotland, you probably will feel the ghostly presence of the people who, for thousands of years, have lived on this land. We felt this most strongly on the isle of Gometra, a smallish island with only two permanent residents. We spent three days in a bothy with no electricity, eating food that we carried in (an eight-mile walk across the isle of Ulva is required to get there) and cooked over a camping cooker. In the evening, we sat by a coal fire, with a candle and our headlamps for lighting.

Here are some of our photos.

Standing stones near Lochbuie on the isle of Mull. Click here for high-resolution version.

Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Moy castle (15th Century), near Lochuie on the isle of Mull. Click here for high-resolution version.

JaneAnne’s bothy on the isle of Gometra. Click here for high-resolution version.

JaneAnne’s bothy. Click here for high-resolution version.

Cooking on Gometra. The home-baked bread was a gift from a B&B-keeper near Calgary. Click here for high-resolution version.

Cooking on Gometra. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

The bridge between Ulva and Gometra, at low tide. Click here for high-resolution version.

Island-hoppers, who often put in here in fine weather, call this “the harbor” between Ulva and Gometra. Click here for high-resolution version.

The big house on Gometra. Click here for high-resolution version.

Gometra, looking across the channel from Ulva. JaneAnne’s bothy is a the lower center-right, and the big house is near the top. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

The long hike across Ulva to Gometra. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

From Ulva, looking toward Mull. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

A wary herd of deer on Ulva. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

A fleeing stag on Ulva. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

A haunted evening begins on the isle of Gometra. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Hiking through bracken on Ulva. It was September, and the bracken was turning brown. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Ulva has no roads — only narrow tracks that are often muddy or covered with water. Click here for high-resolution version.

Photo by Ken Ilgunas

Crossing Ulva to get to Gometra. Click here for high-resolution version.

Ulva. Click here for high-resolution version.

The ferry between Mull and Ulva. Click here for high-resolution version.

Ulva. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Ulva, looking toward Mull. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Haunted Ulva. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Haunted Ulva. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Sheep on Ulva. Try not to get dizzy. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

The memorial, which he himself built, to the man who brought the Clearances to Ulva. Photo by Ken Ilgunas.

Ken, on Mull.

David, at Oban. Photo by Ken Ilgunas.

Ken, near Calgary on Mull. Click here for high-resolution version.

Near Calgary on Mull. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Heather, near Calgary on Mull. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

It his said that the last resident of his village, now a ghost village near Calgary, hanged himself on this tree after the Clearances of the 19th Century. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Ken, near Calgary.

Oban. Photo by Ken Ilgunas.

Oban. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Oban.

From the ferry, near Oban. Click here for high-resolution version.

From the ferry, near Oban.

Tobermory. Click here for high-resolution version.

Tobermory. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Lockbuie, from the side of Ben Buie. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Lockbuie, from the side of Ben Buie. Click here for high-resolution version.

Ben Buie (altitude 717 meters, 2,352 feet) from near Lochbuie. We climbed it, ascending along the long ridge of the shoulder to the right, and descending by the steep rock face and bog land facing the camera. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Ken at the crest of Ben Buie. We started at sea level and gained this altitude on foot. At times there were sheep tracks on the way up Ben Buie, but rarely was there anything that looked like a trail. Click here for high-resolution version.

Lochbuie from the crest of Ben Buie. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

David on the ascent of Ben Buie. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

David on the ascent of Ben Buie. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Working my way up the long ridge toward the crest of Ben Buie. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

David on the descent from Ben Buie. I’ve cleared the worst of the rocks, but at least 2,000 feet of scree and bog are still below me. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

If you hike the Scottish isles, you will be walking in bogs. The bogs are everywhere, whether you are high or low. Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.

Those who live here

If you stay in bed and breakfasts, and if you get out and about, you will meet many of the people who live here (and the creatures they keep). I often wondered how they maintain such a good attitude toward visitors, because the pressure of tourism must be stressful at times.

Still, living in such an old land, and with such long memories, I suspect that those who live in these haunted islands are very much aware that we are all just passing through. And, especially with Americans, I think that the locals often assume (and correctly so) that many visitors come to Scotland to seek their family roots. The diaspora caused by the Highland Clearances has a way of coming home. Those whose ancestors were forced to leave have an enduring claim on this land. The local respects that.

Most of the readers of this blog, like me, are not particularly young. The day will come when the young will leave us behind, and soon enough even the young will have their turn at being old. Until then, keep up with the young for as long as you can. Make sure that they know your stories. Prepare them for being haunted. Hauntedness is a good thing.

Roc Sandford, who owns the haunted isle of Gometra, wrote a little book that you can buy in the honesty store there. He closes his book with these lines:

“And I have not spoken of Gometra’s subconscious, which can be felt distinctly by the unearthly and unearthed, an alluvial mix of misery and enchantment, laid down by all those who lived here once and are now gone, and to whom we too shall soon be joined.”

Photo by Ken Ilgunas

Photo by Ken Ilgunas

Photo by Ken Ilgunas

Photo by Ken Ilgunas

Photo by Ken Ilgunas

A few notes

I was in a bit of a rush to get these photos on line. During the next week or two, there probably will be updates, additions, and corrections.

A note on our accommodations: We used Airbnb. We spent three days at Mornish Schoolhouse near Calgary, three days at JaneAnne’s bothy on Gometra, and three days at the Laggan Farm annex near Lochbuie. All three of these places were fantastic. If you’re off the beaten track on Mull, be sure to have a plan for where you’ll eat or buy groceries.

Photo by Ken Ilgunas. Click here for high-resolution version.