It took almost a month to build the new shed up above the garden. For ten years, a shed has been much needed here, because I did not have a place to store the lawn mower, or the tiller, out of the weather. Plus my beloved Jeep needs to be sheltered. But when I stand back and admire how nicely the project all turned out, I can’t help but think: Do we really need so much stuff? Not only does stuff cost money. Storing stuff costs money, too.

At any given time, most of the stuff we all own is in storage, unused. The abbey’s attic and basement are stuffed with stuff that is being stored. In this part of the U.S. (and probably everywhere in the country), “self storage” units are a growth industry. A great many people are renting a place to store all the stuff that they don’t have room for at home.

Many of us aspire to simple living and an uncluttered life. But why so much stuff? When I moved from San Francisco back to North Carolina eleven years ago, the cost of moving my stuff was just over a dollar a pound. I had to ask myself, for everything I owned and wanted to keep, whether it was worth a dollar a pound. My moving cost was about $3,400, which means that, even after I sold, gave away, and threw away a lot of stuff, I still had 3,400 pounds of stuff that I decided was worth a dollar a pound.

I’m going to guess that even our prehistoric hunter-gatherer ancestors had to carry a lot of stuff on their backs when they moved around. For three million years, anthropologists say, humans have been using tools. Those tools probably made the difference between survival and death. Humans started cooking, anthropologists say, about two million years ago. Cooking, as we all know, requires stuff, the kind of stuff that fills up the cabinets in every human kitchen. When early humans started farming, that required infrastructure. That infrastructure was more or less permanently fixed in place, yet people needed wagons. Wagons have been used to carry stuff for about 4,000 years.

I think I have come to the conclusion that living without stuff would be impossible, and that we should not feel guilty about acquiring and storing a reasonable amount of stuff. All sorts of specialized stuff — in the form of tools — was required just to build the new shed: saws, drills, impact drivers, measuring devices, levels, post-hole diggers, shovel, wheel barrow, and lots of ladders.

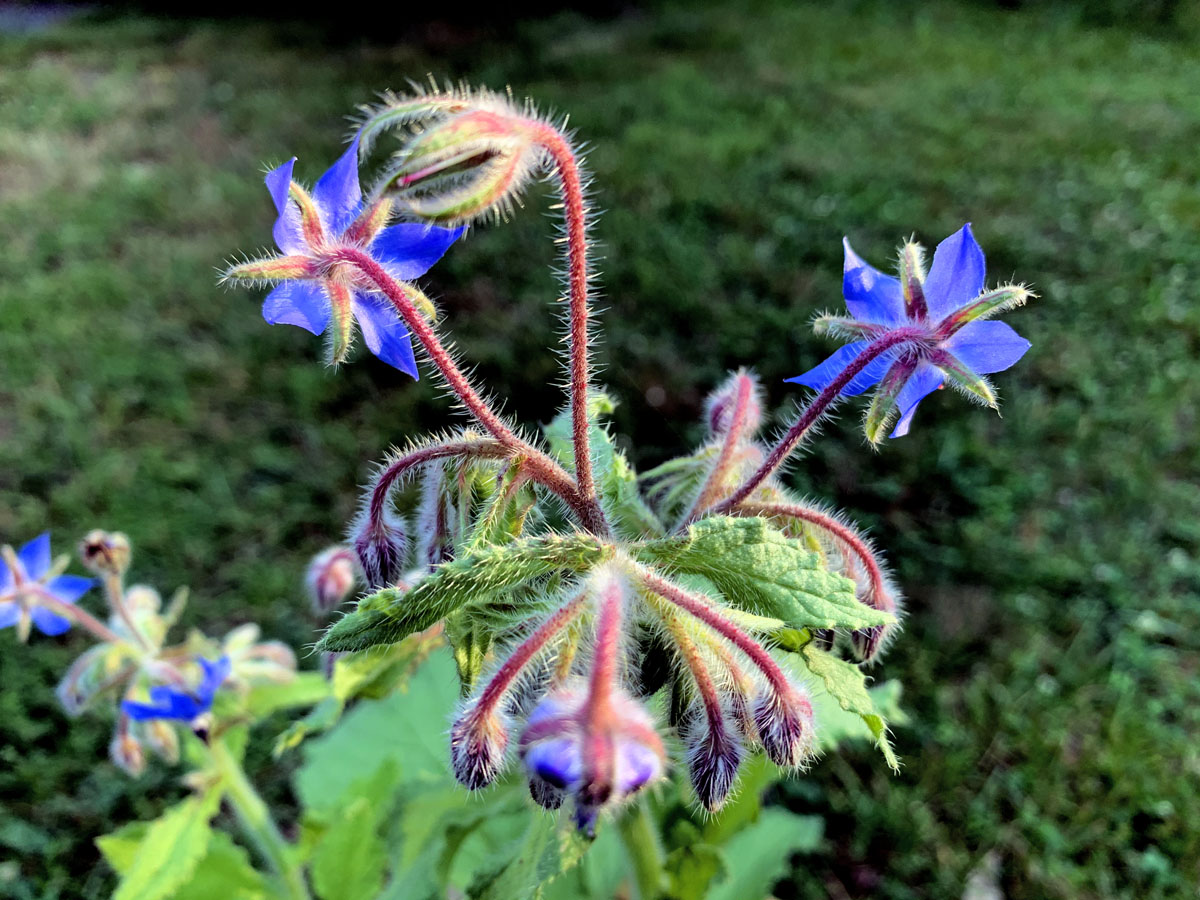

Even a simplified and sustainable life requires not just tools, but also infrastructure. You can’t grow food without a lot of stuff: fields (or at least a garden plot); some form of plough and something to pull it (a tiller will do for a small operation); tools (such as hoes); fences; a way of handling mulches, manures, and composts; and, if your life depends on what you grow, some form of irrigation.

Infrastructure, really, is the biggy. Once human beings migrated out of the tropics, a lot of infrastructure was required for a settled subsistence: A house secure against the weather, a source of heating, a source of water, a system for cooking, places to sleep, systems for sanitation, sources of fiber (such as flax or wool) and systems for turning fiber into clothing, and so on. But we human beings don’t want to settle for mere subsistence. We also want comfort and a reasonable level of convenience.

I’ve resolved to not feel too guilty about acquiring (and consequently storing) stuff — particuarly when that stuff supports sustainability. I do try to ask myself, though, before I buy something: Where will I store it, and how will I maintain it? Maintenance of stuff can be expensive, especially things that have engines, such as vehicles, mowers, and tillers. Maintenance (of the house, of the house’s systems and appliances, and of vehicles) is one of the bigger categories in my budget.

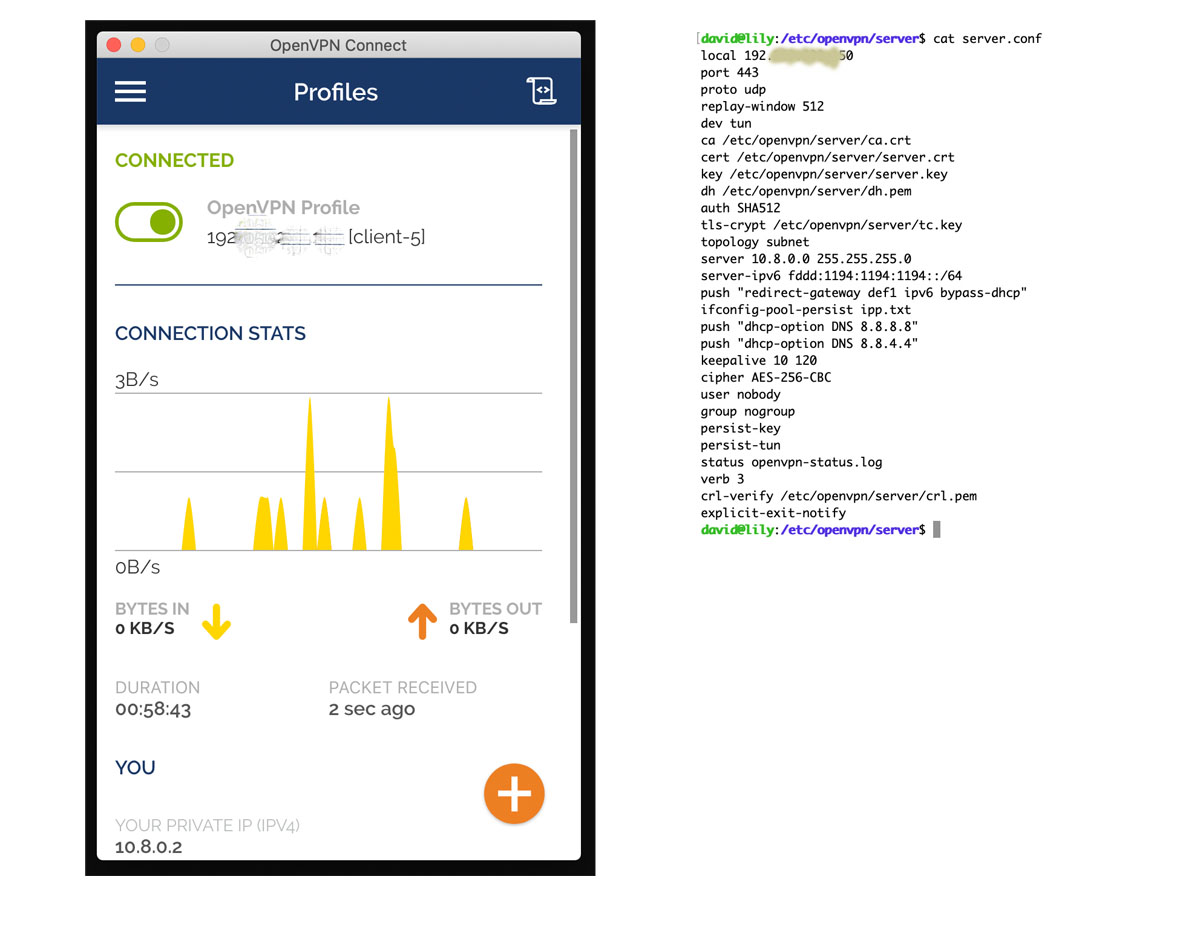

Two optional forms of infrastructure were relatively easy to add to the new shed. A gutter catches the water off the roof and directs it to the 250-gallon tank that feeds the garden’s irrigation system. There’s also a small solar system. At present the solar system provides only lighting and a way of keeping the Jeep’s battery charged (the Jeep often is unneeded and unused for weeks at a time). But even a small solar system can provide some options during a long power failure.

Most people prefer to live, and build, on flat terrain. I, however, love hills, mountains, valleys, and slopes. Flat terrain makes me feel bored and uneasy. There is virtually no flat place in the abbey’s land here in the Appalachian foothills. Thus the shed had to be built on a slope. The shed is 16 feet long, and the ground at one end is almost three feet lower than at the other end. That made the job more complicated, with one end of the shed almost 16 feet high. But slopes have their advantages: gravity. The shed is higher than the water tank, and the water tank is higher than the garden. So the irrigation system can be fed by gravity. Just turn a valve, and the garden gets watered with last week’s rain. That’s infrastructure!

The shed was a pandemic project. Ken did most of the work, but a neighbor also volunteered many hours of his time, tools, and know-how. Lucky for me, I got the new shed for the cost of the materials.