Volunteer cabbage

I should have noticed the possibilities for winter gardening long ago. I suppose it was that I was conditioned to think that gardening season ends with the frost or with the first hard freeze. But that’s not true. There are many vegetables that will keep growing, though slowly.

Certainly some winters are milder than others here in the Appalachian foothills. This was a mild winter, with a winter low of about 15F. The brutal cold that hit Texas and much of the northern and central U.S. this winter never got quite this far east. Some winters are cold enough to damage my fig trees. But I’m expecting a fine fig season this year.

There is an upside to warming, in the form of a longer growing season, as long as an increasingly unstable polar vortex doesn’t spill arctic air onto you, as happened in many parts of the northern hemisphere this past winter. So, winter crops are a bit of a gamble, but I can now see that it’s always worth trying.

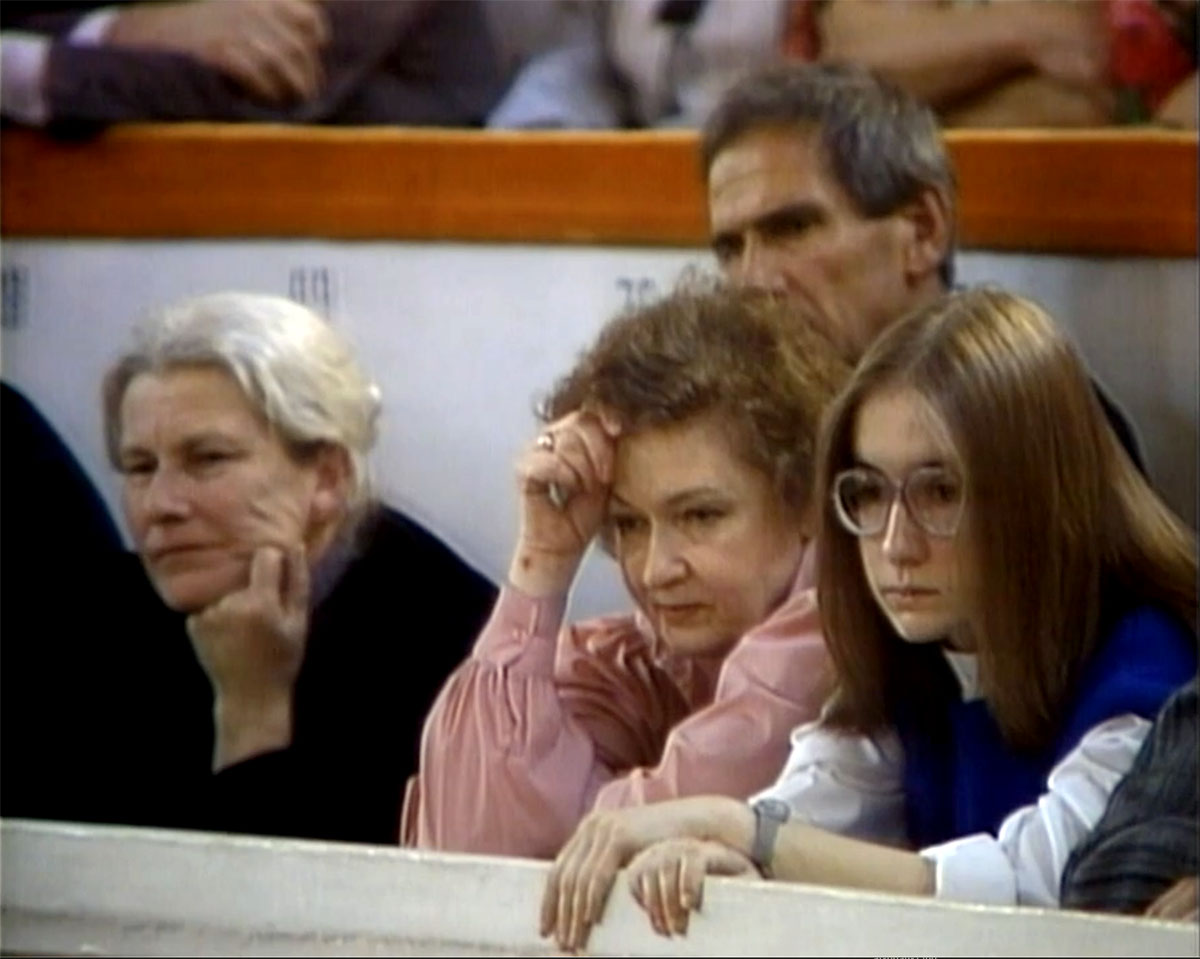

The evidence was right in front of me this winter. I didn’t plant fall greens and turnips. But the neighbors did, and their garden was green all winter. I had mustard greens from their garden in December. Just two days ago, the neighbors pulled all their turnips before doing their first spring plowing. They brought me a bag full of very fine looking turnips.

All winter long I admired a mustard plant growing behind the step on the side porch. My guess is that, last spring, when Ken was sitting on the porch in the morning sun, sorting seeds, he dropped some mustard seeds. The mustard plant got only morning sun on the eastern side of the house, but it flourished all winter. I also had a winter cabbage plant. I often throw the stalky remnants of cabbages under the rhododenron bush on the north side of the house, because Mrs. Squirrel loves cabbage stalks. My guess is that a cabbage stalk, with plenty of moisture available, put down roots and sent up leaves. I will leave it there and see if it makes a cabbage head this spring.

All of these observations show me that, not only are some things willing to grow in the winter. They’re eager to grow.

To get an earlier start with the garden this year, I’ve bought a cold frame, which I plant to set up around March 15. I’ll have photos of that project when the time comes. My resolutions for better gardening this year include extending the growing season both in the spring and the fall. I get burned out by summer gardening, overwhelmed by heat, humidity, and weeds. But this year, I resolve to get back into the garden in time to start a fall and winter garden.

Another gardening resolution this year is to grow, and use, more fresh herbs, starting them in the cold frame. I plan to focus on herbs that can go into pestos — lots of basil, of course, but also parsley, dill, and cilantro. I could easily become a pesto fanatic. There are many YouTube videos on making pesto in which cooks swear that pestos are better when made the old-fashioned way — with a mortar and pestle rather than a food processor. That’s something I have to try. Certainly garlic is not really garlic unless it’s crushed rather than chopped. I’ve got to discover whether that’s also the case with basil.

The long-range weather forecast here calls for a mild, wet March. That sounds perfect for getting an early start in the garden.

The mortar and pestle, by the way, came from Amazon and is made of granite. It was the biggest mortar I could find on Amazon, 7.1 inches in diameter.

Volunteer mustard

One of the turnips the neighbors gave me

A new mortar and pestle for pesto