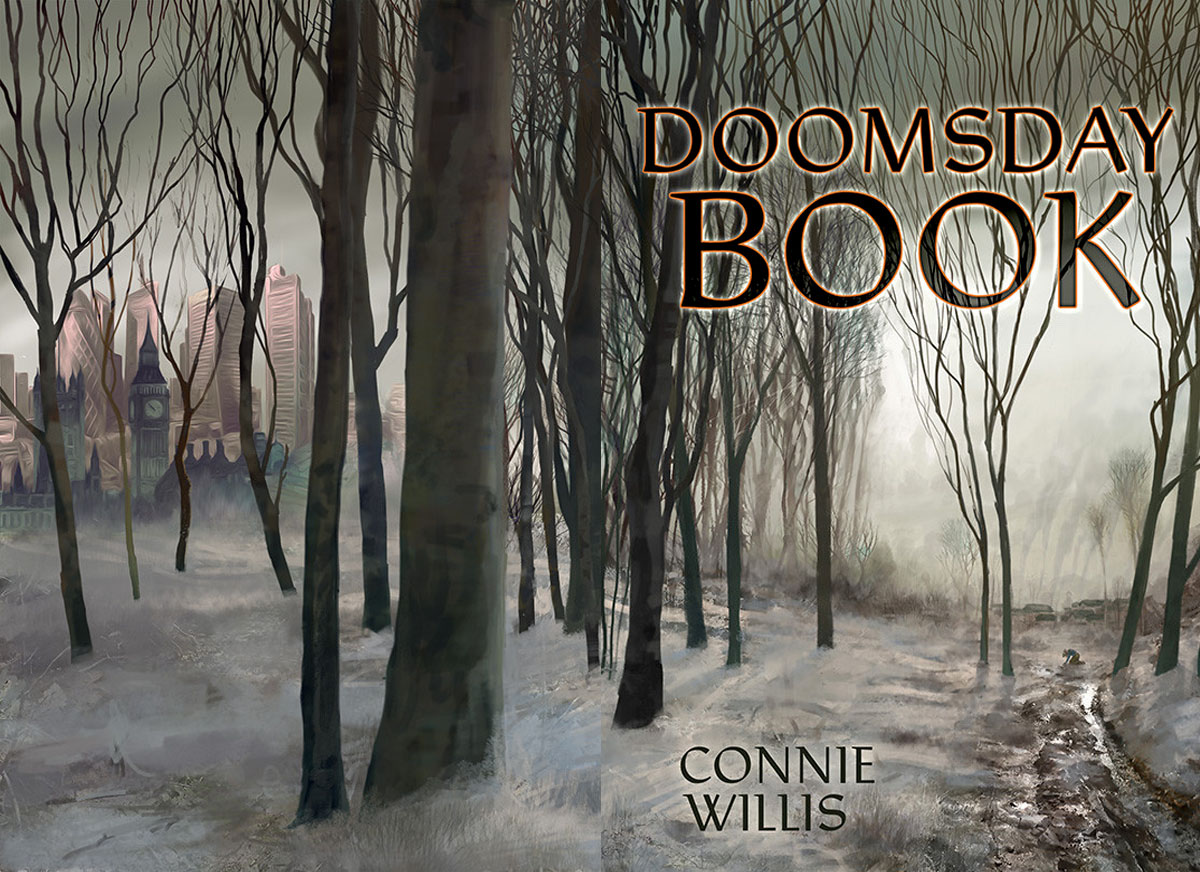

Doomsday Book, by Connie Willis. Bantam Spectra, 1992. 608 pages.

The title is a warning: This book is going to be about doom. To avoid spoilers, all the reader should know before starting the book is that it’s about time travel to the 14th Century, and that the plot has to do with the plague. If the Covid-19 lockdown has got you down, this book won’t be good for your mental health. Despite its flaws, Doomsday Book has earned its place in the apocalyptic section of everyone’s bookshelves.

I considered flinging this book several times, even after I was a few hundred pages into its considerable length. Connie Willis, who is one of a small group of our most competent living science fiction writers, ought to know better than to let a novel drag along so slowly for 400 pages, the first two-thirds of the book. This novel won both the Nebula and Hugo awards in 1992, and Connie Willis was named a grandmaster of Science Fiction Writers of America in 2011. She (and her editor) should have realized that such weak or non-existent subplots are not enough to keep the reader engaged for a long, slow 404 pages until the plot is finally off and running. One Amazon reviewer writes, “I finally couldn’t take it anymore and simply gave up.” I stuck with it, because many of the characters are appealing, and because I fell under the spell of her Oxford and medieval atmosphere.

It would be easier to review this book by dividing it into two parts.

The first two-thirds: Almost all the scenes are too long. Almost all the conversations include some pitter-patter. Rather than strong subplots presenting obstacles to the characters’ striving, the obstacles (of which there are a great many) are rarely more than frustrating and meaningless little aggravations — somebody can’t remember something, or someone is on vacation and can’t be found, or a petty official forbids something, or the weather gets in the way. Sometimes the pettiness has the feel of slapstick. But Willis does have a pretty good sense of humor, and that helps. This meandering is not a total loss, though. By the time we’re 400 pages in, a lot of good character development has gotten done, and the scene-setting is excellent even when it is suffocating. A romp around medieval England would have been fun and easier to write, but Willis rightly chooses to keep the characters in one place, locked down, in the dark about their circumstances, miserable, often crossways with each other. After all, the plague is not something that one goes questing for. The plague comes and finds you, even if you try to hide.

I give Willis high marks for her theology, a subject that is bound to come up in a story in which there are last rites, lots of Latin, graveyards, and so many church bells. I also would give Willis high marks as a psychologist, as she makes the point that certain types of people will be with us in any century — the noble few, the hordes of the ordinary, and those who specialize in being insufferable.

The last third: With the key to the plot revealed at last (not that it was hard to figure out), the story is off and running. The slow investment in characterization and setting pays its dividends. The level of danger escalates rapidly. The misery of the characters starts to seem sadistic, but as Kivrin, the main character, reminds herself, “It’s a disease. No one is to blame” — except maybe God, an idea that Willis invites us to see through modern eyes as well as medieval eyes, and through the eyes of the noble as well as the insufferable. In spite of the slow start, Willis ends up weaving a spell so intense that my reality started to blur a bit. Partly it was the weather, in which my local atmosphere was like the atmosphere in the story — cold rain and ice, dark skies, a cat by the fire, masks, and not going anywhere if one can help it. And though the pandemic in the here-and-now has been nothing like the plague of the 14th Century, one never really knows how bad things might get before a pandemic finally starts to recede.

Would this novel be as compelling if read in the merry month of May? I don’t know. I’d say it’s a winter novel, if you can handle it.