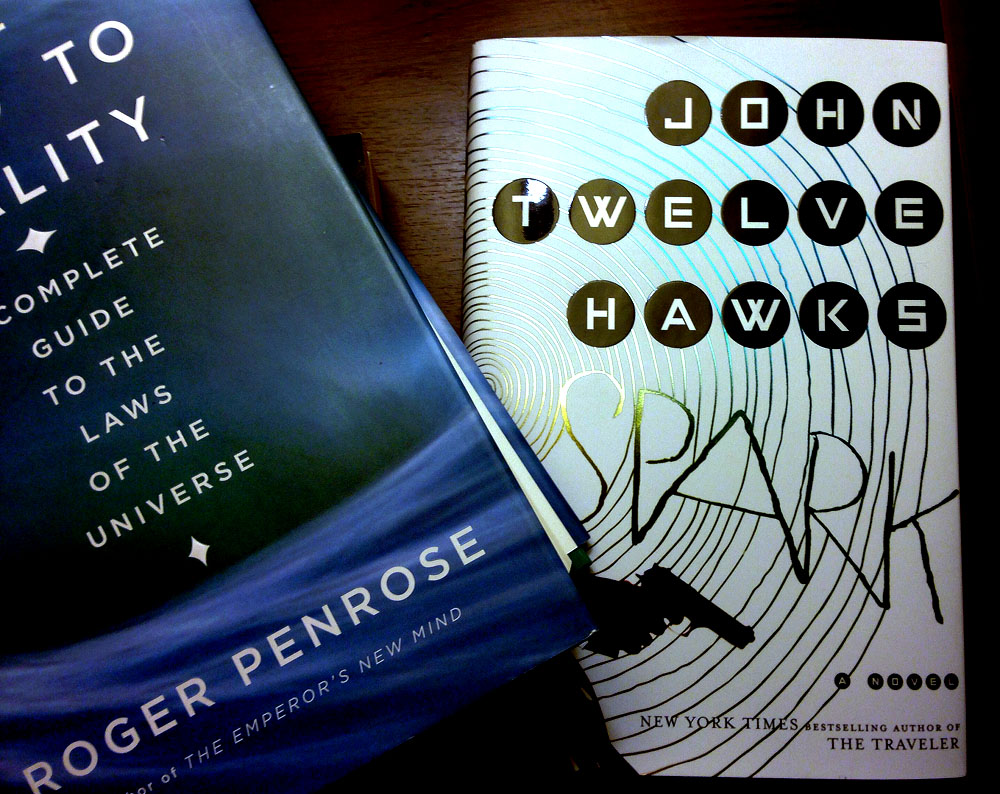

John Twelve Hawks’ newest novel Spark was released on Oct. 7, and I actually bought it that week. But I was slammed with election duties during the month of October, so I put the book aside until quiet times returned. This is because I knew that Spark would be a barn burner of a page turner. It was, and I read it in a day and a half. Brilliant writers like John Twelve Hawks don’t really need yet another glowing review, so I’d like to get off onto a sidetrack for a moment — readers.

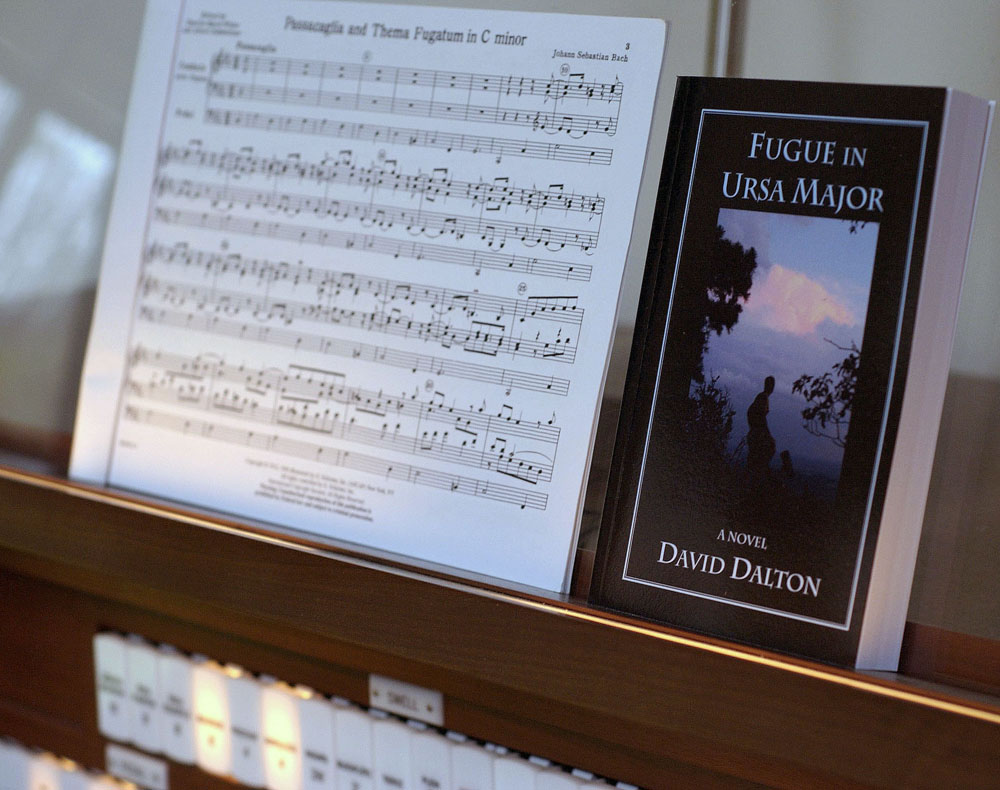

I have become fascinated with bad reviews, because bad reviews tell writers something that writers need to know. I’ve recently gotten into the habit, both with books I’m about to buy and books I’ve already read, of looking at the most negative reviews that can be found on Amazon. This probably started when Fugue in Ursa Major got its first 3-star, as opposed to 5-star review. I was insulted by the reader/reviewer’s sheer stupidity, and I needed to assure myself that everyone’s books are misunderstood. There’s a rule among writers about never responding to a bad review. But there is no rule that says you can’t respond to bad review of someone else’s book.

Here’s a snippet from the “most helpful” negative review of Spark, which has the headline “Meh.” I’m fixing the reviewer’s multiple typos:

“Honestly, the first half of the book was so dry and boring, I really wasn’t sure I would be able to finish it. … Part of the problem was the bland writing since the protagonist has no feelings, diagnosed with Cotard Syndrome (delusion of being dead) that there is no dimension to him. I really didn’t like him much or even care what was going on.”

Why do people who know (or care) so little about novels, characterization, and storytelling even bother to read? They are stuck inside their own tiny minds, not seeking any sort of expansive experience in a book but rather seeking to have their own smallness affirmed. But any reader with a clue about how stories work knows that, if a writer starts a story with a character who is incapable of affect and who thinks he is dead, then that character is going to undergo some sort of transformation during the course of the story. A good reader also will be alert to what’s between the lines. Maybe the author wants us to think about our feelings and when feelings matter (or don’t matter). Maybe he wants us to think about what’s worth living for, or whether we’ve even alive at all. A good reader also will know that, very often in good stories, characters change during the course of the story, and the nature of that change is an important part of what that story is about. It’s like starting with a hard-hearted character like Ebenezer Scrooge and asking ourselves, “What kind of experiences might change this bitter old man into someone warm and caring?” Thus Charles Dickens gave us A Christmas Carol. What if a clueless reviewer wrote, “I just couldn’t get into this story. The Scrooge character was just so one-dimensional and mean that I couldn’t care about him. So I couldn’t finish this book.”

Bah! Humbug!

If John Twelve Hawks (he’ll almost certainly Google up this review and read it) will forgive me for plugging my own book in a review of Spark, I got a similar comment in a review of Fugue in Ursa Major on the bad-taste book site Goodreads:

“The main character was a basket case unable to form relationships and he is saved. Only a hero that Ayn Rand would love, but I could care less.”

She is talking about my Jake. (Coincidentally, John Twelve Hawks’ main character in Spark also is named Jake.) As a bad reader, she does not understand that if a writer starts a story with a character who is having trouble with relationships, then during the course of the story that character is probably going to learn something about relationships. As for Ayn Rand, the reviewer is so insensitive to the clues that every writer lays between the lines that she can’t detect that I abhor Ayn Rand. I suspect that particular reviewer was blinded by her rigid political agenda. Reading, to her, is about comfort and confirmation in her own tiny world.

But back to Spark and the mystery of John Twelve Hawks. I’ve written about him previously, here, here, and here. He is a master of the hot read. I read him partly to study his style, in particular his action scenes, because I’m not good at writing action scenes. His prose is the kind of prose I like — transparent prose that tells the story without language getting in the way. In fact we’re hardly aware of language at all. His style is very cinematic, which is why I was not surprised that he got a big movie deal for Spark.

What I would love to know is how he learned to write. It can’t be just raw talent (though he has plenty of raw talent), because every writer works from a theory of writing whether he knows it or not. John Twelve Hawks dots all the i’s and crosses all the t’s. Everything is properly foreshadowed. There are no wrong notes. He stays on course for his destination: a ripping good conclusion. By the end, all the many threads of the story have been tied together, and every character has gotten his lines just right and played his role perfectly. It’s a masculine, muscular style that would not work for the kind of stories that I want to tell, but it’s perfect for the stories that John Twelve Hawks tells.

Which brings me to what I think is the most important question we might ask about John Twelve Hawks as a writer. Why does he choose to tell the kind of stories he tells? Having asked that question, I’m not going to try to answer it. Because only writers, not reviewers, can speak to readers on a question that important. But I think it’s much more than wanting to deliver a hot read. And, whatever his purpose is, I’m pretty sure that I wholeheartedly agree with him.