I am in the thick of revisions in Fugue in Ursa Major. A couple of days ago I was working through a section in which the story’s young hero is trying to figure out what the hell is going on in the world. He sees some strange things, but he doesn’t know what it means. He realizes that if he paid attention only to official sources of information, or to our crappy media, he’d never know what’s really going on. So he tries to study up on the science of intelligence analysis and connect some dots.

In this section of the book, I went on for several pages with my own ideas about acting as our own spies and how we might go about doing this. I included a pretty bitter indictment of the failures of our media and the swamp of propaganda and distraction in which we all must operate.

Months after I wrote this section of the book, I got a copy of the recent book Conspiracy Theory in America by Lance deHaven-Smith. My own thinking and my own critique of our contemporary information environment are so much like deHaven-Smith’s that you might think I cribbed those ideas from deHaven’s book. But I didn’t.

Here’s a quote from the jacket copy of deHaven’s book:

Conspiracy Theory in America investigates how the Founders’ hard-nosed realism about the likelihood of elite political misconduct — articulated in the Declaration of Independence — has been replaced by today’s blanket condemnation of conspiracy beliefs as ludicrous by definition. Lance deHaven-Smith reveals that the term “conspiracy theory” entered the American lexicon of political speech to deflect criticism of the Warren Commission and traces it back to a CIA propaganda campaign to discredit doubters of the commission’s report. He asks tough questions and connects the dots among five decades’ worth of suspicious events. … Sure to spark intense debate about the truthfulness and trustworthiness of our government, Conspiracy Theory in America offers a powerful reminder that a suspicious, even radically suspicious, attitude toward government is crucial to maintaining our democracy.

Now the reaction of a smart person to this proposition might go something like this: OK, but how do you distinguish between the crazies and their crazy conspiracy theories and the process of diligently trying to connect the dots?

I think the answer to that is pretty easy. Crazy people aren’t trying to understand what’s really going on in the world. Far from it. Rather, they have an ideological agenda, and they’re trying to make the real world conform to the craziness inside their own heads. Often this is religious craziness. Almost always it’s some kind of ideological craziness. And the crazy kind of people aren’t being diligent and scientific at all. They’re dishonest, stupid, and credulous.

But we aren’t like that are we?

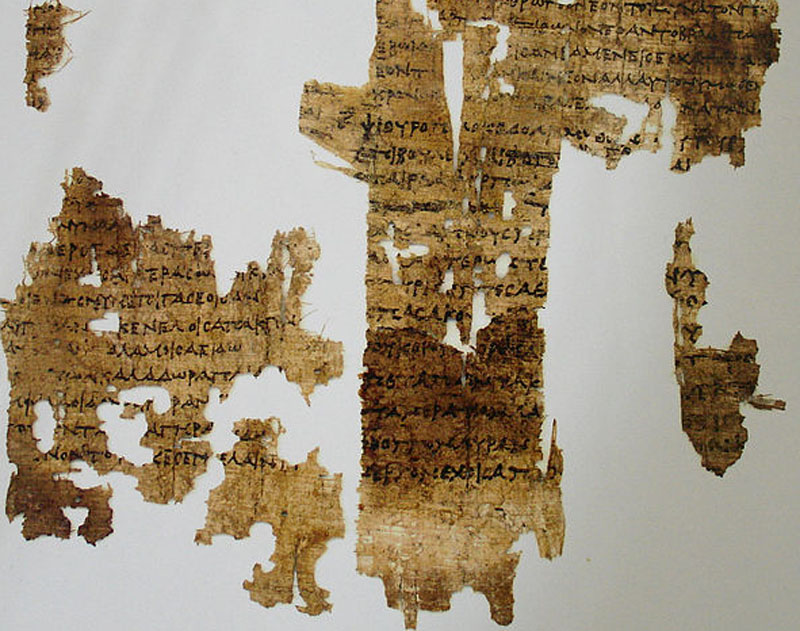

Writing Fugue in Ursa Major required quite a lot of research. Though the story begins in the here and now, I have a lot to say about the past and how the world came to be the way it is today. In particular, I’m concerned with the history of classical Greece, the rise and fall of Rome, and the beginning of the Dark Ages. I’m no scholar, but this kind of research actually is a lot of fun to do. When, in the novel, my characters talk about how the world used to be, I want their thinking to be plausible and academically defensible. For that reason, I don’t mess around much with popular histories. I read the academic stuff. So, when you read Fugue in Ursa Major, you may wonder at times, “Was it really like that back then?” And my response would be, “To the best of our knowledge, yes it was.”

Conspiracy Theory in America, by Lance deHaven-Smith. The University of Texas Press, 2013. 260 pages.