Unless a novel becomes a classic, it will become obscure. It may or may not show up on book lists. There probably won’t ever be a Gutenberg edition. The review industry, of course, is concerned with what’s new. How might we discover now-obscure books that were published before we were born?

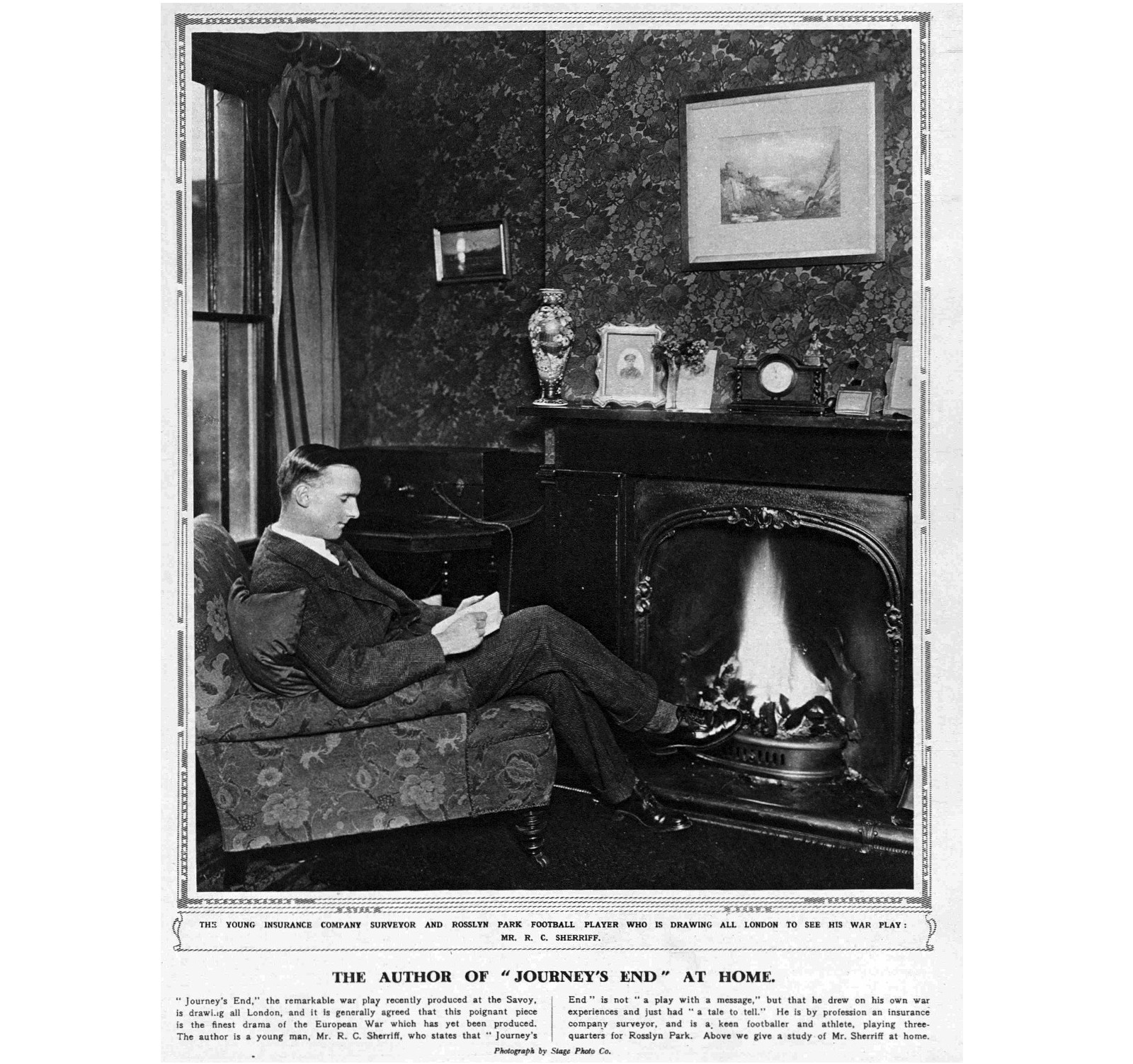

With R.C. Sherriff’s The Hopkins Manuscript, first published in 1939, a kind of miracle brought it to our attention. The publisher brought out a new edition, and the Washington Post wrote about it: “The moon falls to Earth in a 1939 novel that remains chillingly relevant.”

I ordered the book immediately, of course. It’s a post-apocalyptic novel that never showed up on the many lists of post-apocalyptic novels that I had scoured. I bought a used hardback copy on Amazon that I assumed would be the 1939 edition. But when the book arrived I was surprised to discover that it’s from 1963 and is some sort of book club edition. That means that there have been three editions of The Hopkins Manuscript.

I’m only 52 pages into the book and will write more about it later. It’s beautifully written, something we might expect from an author who was educated at Oxford and who also was a playwright.

Yesterday Ken, who knows I’m on the lookout for memorable science fiction and fantasy that has fallen into obscurity, sent me a link to an article about Hope Mirrlees: “Hope Mirrlees and her curious masterpiece.” Mirlees was a lesser-known member of the Bloomsbury Group. One of her poems was published by the Woolfs’ Hogarth Press. The novel is Lud-in-the-Mist, first published in 1926 and now in the public domain. I’ve ordered a copy of Lud-in-the-Mist from a used book seller. I assume it is the 1926 edition, though someone — I’m not sure who — has reprinted it in paperback now that the book is in the public domain.

Why was it so easy to find good science fiction and fantasy up through the 1980s? Was it only because, 35 years ago, there was so much that I had not yet read? Or has something changed, either in what people want to read or what publishers choose to publish?

I’m very suspicious about the current state of the publishing industry. This piece in the Times of London increased my suspicion: “Publishers cower in fear of ambush by woke critics.” (Unfortunately the article is behind a paywall. I read it through my subscription to Apple News.) As I’ve said here before, as very much a liberal I’m in accord with the principles that conservatives deplore as “woke.” But that doesn’t mean that I want to read novels that have been pre-policed to make sure they don’t offend anyone. While I’m gasping for a good space opera (which were plentiful in the 1980s), that’s not the sort of thing that publishers seem interested in these days. (I do note, though, with some optimism, that John Twelve Hawks reported on Facebook yesterday that he has finished the draft of a new novel.)

The classics are always there for us, if publishers let us down. I greatly enjoyed the time I spent reading seven of Sir Walter Scott’s novels. Thus I was particularly amused to find this passage on page 42 of The Hopkins Manuscript:

“But I knew that I must do something to preserve my sanity, and after long thought I resolved upon what may seem a pathetic attempt to alleviate my awful loneliness. I resolved to read from beginning to end the works of Sir Walter Scott. I possessed these in thirty volumes, and one a week would carry me far into the winter — even until the day when I should no longer need to nurse my secret.”

The Hopkins Manuscript is often laugh-out-loud funny. I understood the passage above to be an example of Sherriff’s dry humor: Just how pathetically bored would someone have to be to read so much Walter Scott, which lots of people possessed in thirty volumes, but none of which had been read? You can still buy those sets, complete or not, on eBay and in used book stores.

Is there someone, somewhere — part historian and part booklover — whose mission it is to keep obscure old novels from being forgotten? It would be hard work, and it would require access to the right kind of libraries. These days, shops that sell out-of-print books list them on Amazon or eBay. But how do we figure out what to look for?

As an aside, I might mention here that the World Science Fiction Convention, also called WorldCon, will be in Glasgow next year (August 8-12, 2024). I’m overdue for a trip to Scotland, so I’m hoping to attend. Maybe I’ll be able to pick up some intel on what readers are thinking versus what publishers are thinking. There has been a good bit of protesting at WorldCons during the past few years, mostly from the right.