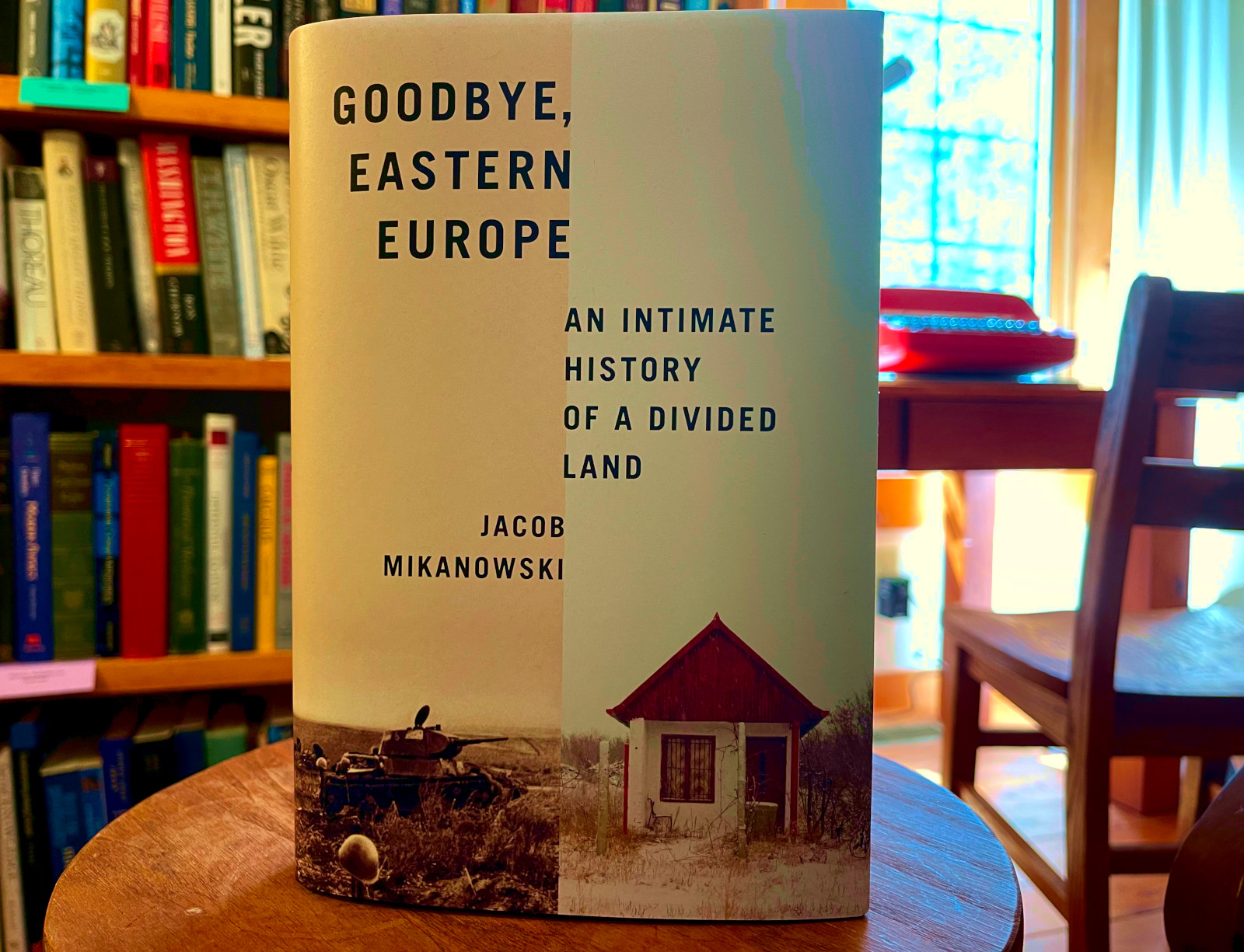

Goodbye, Eastern Europe: An Intimate History of a Divided Land. Jacob Mikanowski. Pantheon, July 2023. 378 pages.

If some perverse god created the earth, then it’s almost as though that perverse god reserved Eastern Europe as a place dedicated to the relentless refinement of human misery. The book describes how life there has never been fair, not any time in recorded history, and not in the present, either.

First I should mention why the title includes the word “Goodbye.” This is explained early in the book and in the jacket copy. No one wants to be from Eastern Europe anymore. The people there would prefer other identities: “Ask anyone today, and they might tell you that Estonia is in the Baltics or Scandinavia, that Slovakia is in Central Europe, and that Croatia is in the eastern Adriatic or the Balkans. In fact, Eastern Europe is a place that barely exists at all, except in cultural memory.”

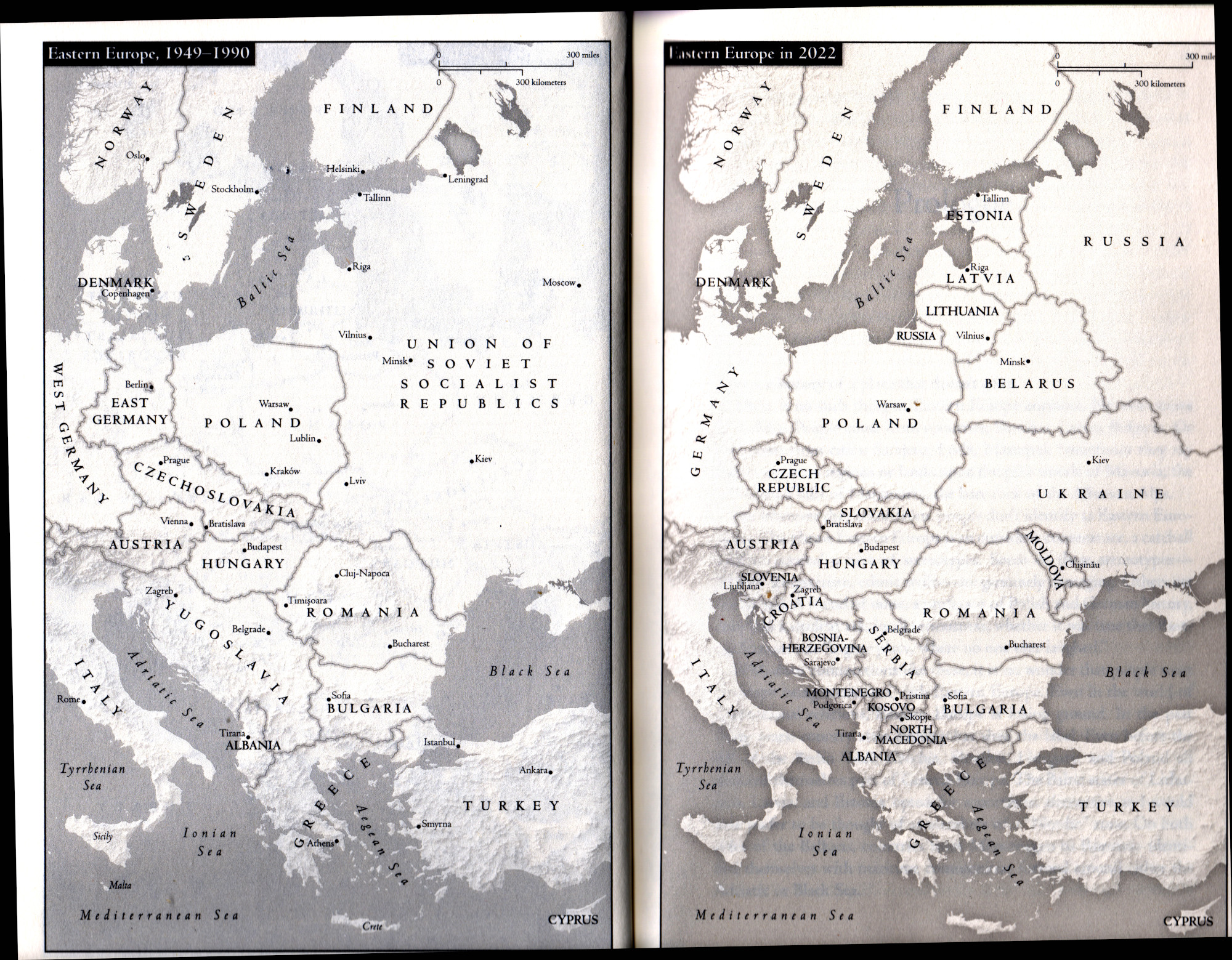

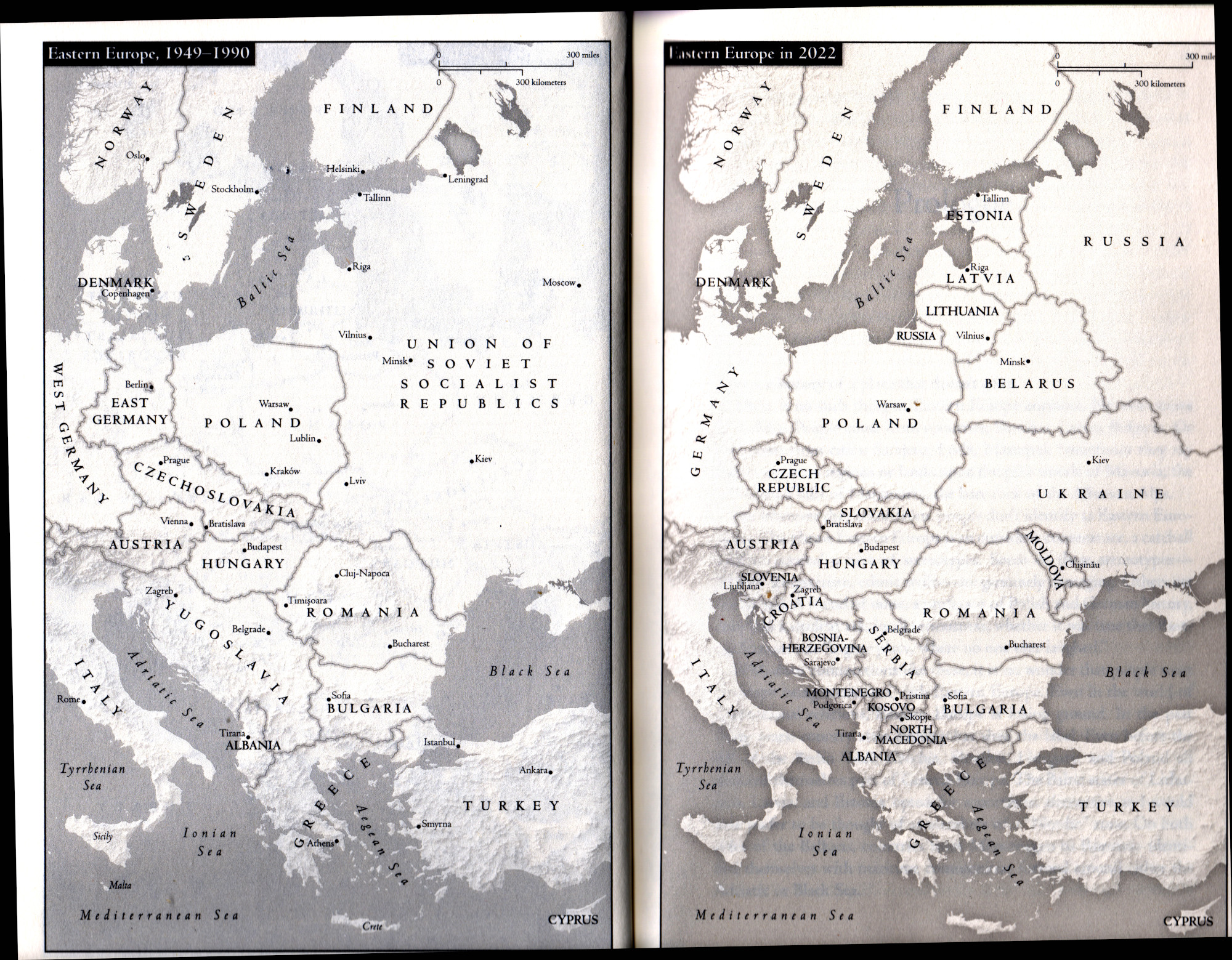

We know even less about the pre-Roman history of Eastern Europe than we do about Western Europe. But we do know that when the Roman religion made its way into Eastern Europe, it was just as brutally violent, including genocides, as it was in the west. Not only did the brutality come from Rome, though. The arrival of religion in Eastern Europe was a triple whammy — the western church out of Rome, the eastern church out of Constantinople, and Islam out of whatever hell it came from, each as horrible as the other. After the Christians came, Eastern Europe was used as a source of slaves, who were sent overland in chains to slave markets in the Mediterranean. At times, Jews were welcomed in some places and were temporarily safe, but for the Jews safety was always temporary. The Roma (the gypsies) rarely had it easy either. Though the agricultural potentials of Eastern Europe were and are enormous, famine and starvation were all too often a way of life, as was war. I think it is fair to say that states and cultures were almost always poorly rooted and precarious, because there was rarely the kind of stability that could be found in Germany, Britain, or Scandinavia. The five maps at the front of the book show how national boundaries have changed since 1648. Every change came with turmoil.

During World War II, westerners learned a great deal more about what life in Eastern Europe was like, starting with Czechoslovakia and Poland. But everyone suffered, from Bulgaria in the south to Lithuania in the north. And then there’s Russia. The west looked away from Eastern Europe after World War II ended, but the human suffering wasn’t over, especially for surviving Jews who wanted to return home from hiding (often in the forests) but found that their homes and properties now had new owners who refused to give it back. Jews continued to die.

Russia’s war on Ukraine has made Eastern Europe visible again to western eyes, but reporting on the war is shallow. Westerners still know very little about what life is like for the people of Ukraine, Georgia, Romania, Belarus, Lithuania, and even Poland. Part of the story is about corruption and what corruption does to those who are exploited by it. My guess would be that the young people of Eastern Europe, as long as they are not deceived by the propaganda pumped out by corrupt states, know vastly more now than was formerly possible, because of the Internet. I can’t help but wonder how long they will put up with it. However the war on Ukraine ends, my guess is that after that war we will see more mass uprisings in Eastern Europe demanding democracy, as we have seen in Belarus after the stolen election there in 2020. Georgia also is a hot spot. As for us Americans, perhaps our interest in Eastern Europe would be greater if we were able to recognize that what the corrupt anti-democratic right wants for Eastern Europe is exactly what they want for us here.

This book, in spite of the light it sheds on that part of the world, really only serves to remind me how little I know.

From the book. Click here for high-resolution version.