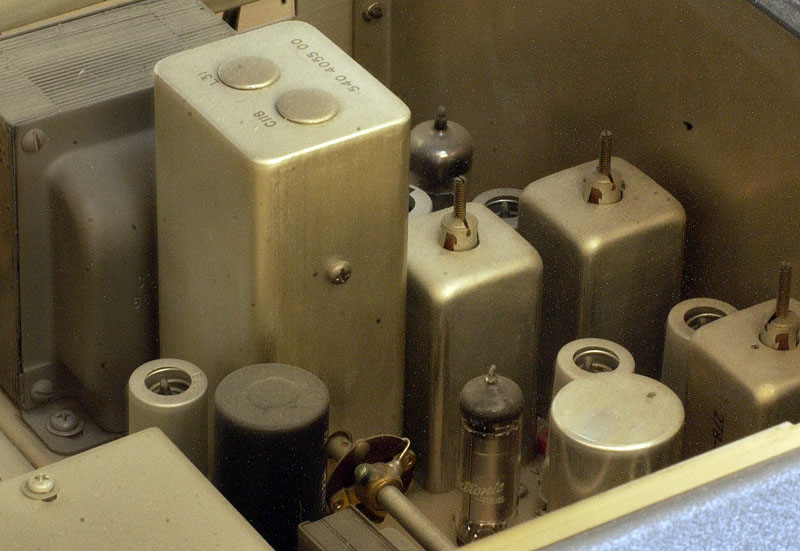

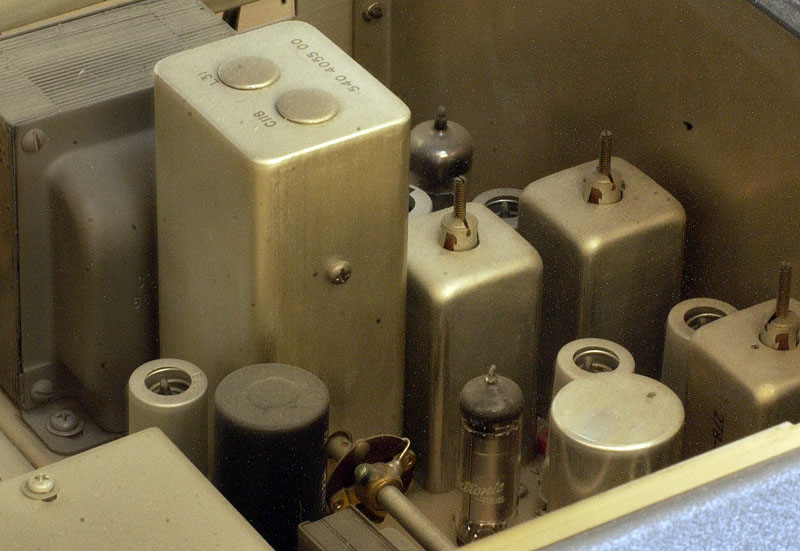

A small area of the interior of my 1954 Collins 75A-4 receiver, which has 22 tubes and lots of rotating shafts attached to its inductors and condensers

It is universally understood that human beings — at least the better sort of human beings — have empathy for other human beings, and for animals. But empathy goes way beyond that. It took me a while to figure out the difference between people with green thumbs and people with black thumbs. I concluded that people with green thumbs have a highly developed empathy for plants. They have learned what plants want. If plants are happy, they feel their happiness. If plants are unhappy, they feel their pain and can’t rest until they figure out what the plant needs to be happy again.

It’s the same with mechanical things, and with electronic things. I have an almost debilitating empathy for mechanical things. Partly, I think, it’s because I’ve been a tinkerer ever since I was a little boy. I grew up in a culture in which boys learned how to use tools and learned how to fix things, things like cars. I did not wreck my toys. Some of my favorite toys, such as a train transformer that I used as a power supply for electrical experiments, lasted for years and years. I would even take it apart periodically and oil its rheostat.

I have a painful awareness of when something mechanical is stressed and is in danger of breaking. Anyone who has been around the abbey for very long knows that I have a seemingly neurotic complex about not slamming doors. Now partly this is because the sound of a door slamming is one of the rudest, most irritating sounds I know. But partly it’s because the abbey’s doors are excessively expensive and complicated, and from the day I moved into the abbey I’ve had premonitions of a door’s latch mechanism breaking, knowing how difficult and expensive it would be to get it fixed. Sure enough, one of the door’s latch mechanisms broke. I described the problem on the phone to a master locksmith, and he empathized with my empathy, warning me how difficult it is to repair one of those fancy German locking mechanisms in a door which has not one bolt but three (tighter weather seal and harder to knock down), not to mention a deadbolt and a special anti-slam finger that tells the mechanism whether the door is open or not, to guard against the bolts shearing if some idiot slams the door while the bolts are extended. Now, I know that not one in a hundred readers understood the mechanics in the previous sentence, but I wrote it anyway as an empathy-raising exercise.

Months before the windshield in my Jeep developed a creeping crack, I had a premonition of it. I swear I felt its stress developing. Two weeks ago, my dishwasher started leaking. I’d had a premonition of that too and had started thinking about what sort of replacement would be best.

When you give a machine a home, it’s like adopting an animal. You take on a commitment to feel that machine’s happiness or pain, and to take care of it. My Jeep needs washing, but it’s impeccably maintained. My god-awful complicated Rodgers 730 organ, now 21 years old, also is impeccably maintained. There’s not so much as a burned-out piston lamp. My IBM Self-Correcting Selectric III typewriter is in excellent working condition.

I don’t have a perfect record. A few weeks ago, I forgot to cover the lawn mower, and rain water got into the fuel tank. Horrible! Some of the garden tools are outdoors instead of in the basement where they belong. My Yaesu FT-897 transceiver could use some work. Boxing it up and sending it back to Yaesu’s excellent repair department is not a priority at the moment, but I feel its pain. And I am absolutely terrible with house plants, which is why I don’t have any and have stopped letting people give them to me.

To be surrounded by things that are broken ought to be a source of misery, similar to the misery of hungry chickens that are late to be fed, or lettuce that is wilting from lack of water.

The local garage that maintains my Jeep has a classic Fifties-vintage Rolls-Royce in storage. Every time I take the Jeep in, I sneak out to the Rolls-Royce, open the driver’s door, then gently close it again, just to hear the sound of its beautifully machined latching mechanism. But every latch, and every machine, especially the lame and the humble and the elderly, deserve our empathy, our respect, and our repairs in their time of need.