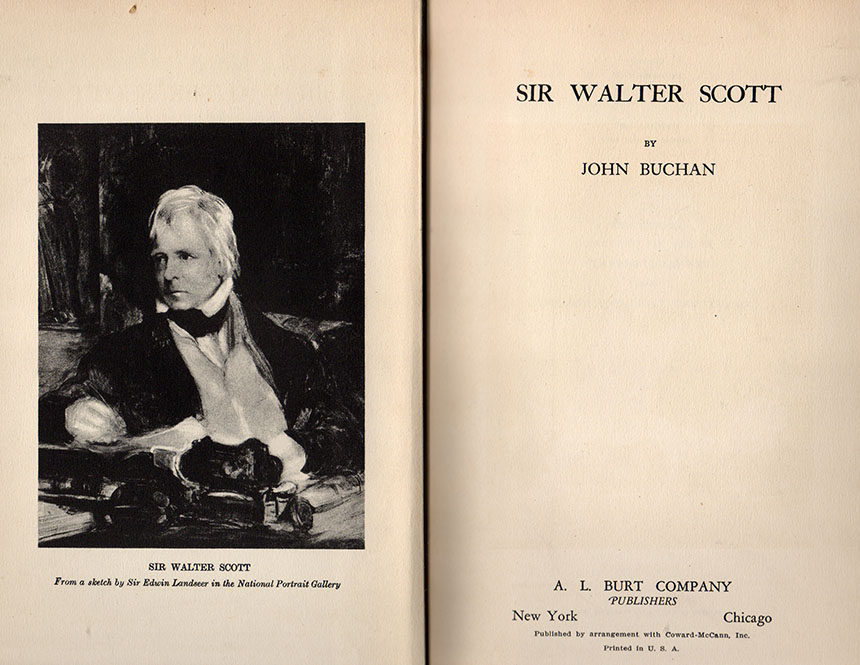

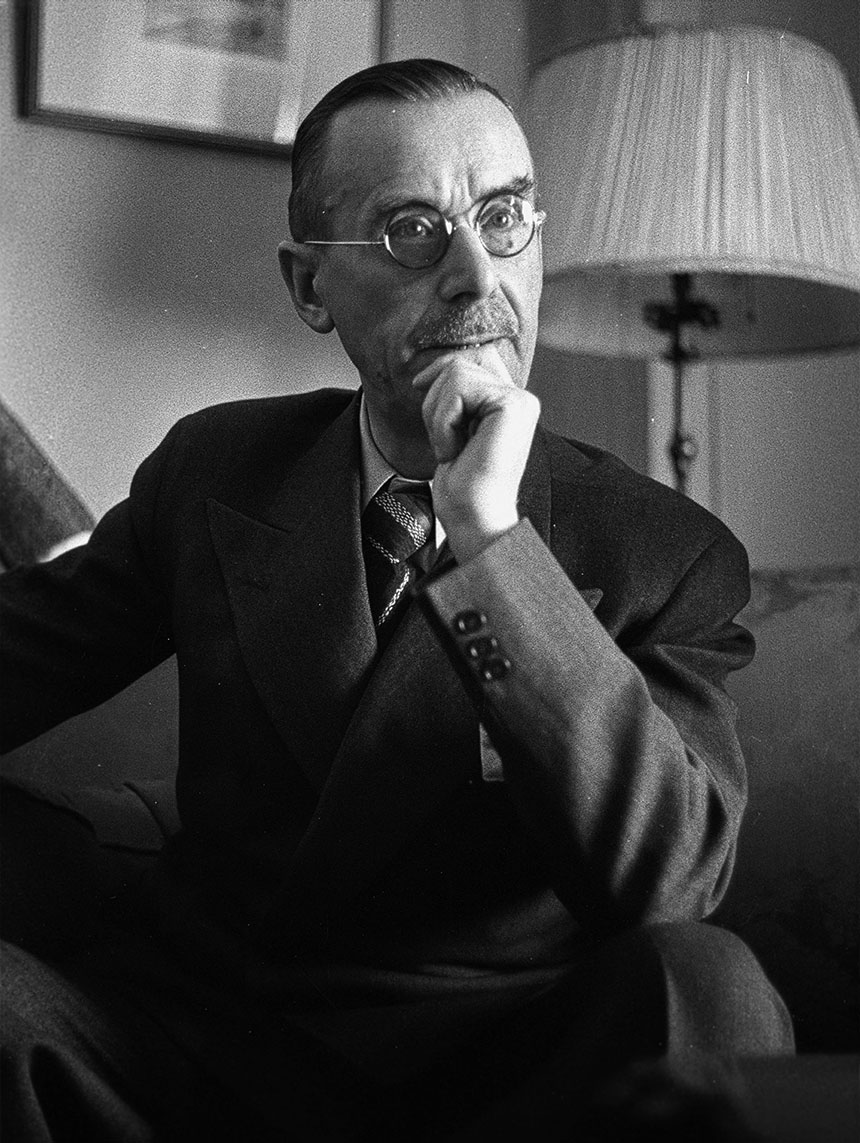

Thomas Mann. He warned Germany, but they didn’t listen. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

If Trump stays on his current course toward global catastrophe, then he must be stopped. If Congress, the courts, and the American people fail to stop American aggression, then who can, other than Europe?

The 77 million Americans who voted for Donald Trump have no understanding of how what is happening in the world today recapitulates what happened in Germany not that long ago.

With Trump’s threats against Greenland, his obvious intention of ceding Europe to Putin, and his also obvious intention of putting down the Western democracies and divvying up the world for rule by autocrats, Europeans are in a terrible bind. They have been there before, and they have not forgotten it.

Are we getting dangerously close to a situation in which the world must defeat Trump because Americans won’t?

According to ChatGPT in research-assistant mode, half a million people left Germany between 1933 and 1945 when they saw where Hitler was taking Germany. Many of those were Jews. About 30,000 were political and intellectual exiles. Thomas Mann was one of them. As early as 1933, he moved to Switzerland. In 1939, he emigrated to the United States.

From America, Mann wrote a series of radio addresses to the German people that were broadcast into Germany by the BBC. Twenty-five of those radio addresses, from 1940 to 1942, are available in the public domain. As far as I can tell, the complete set of radio addresses in an English translation are available only in book form, recently published by Camden House: Thomas Mann’s Antifascist Radio Addresses, 1940–1945.

Here is an excerpt from Mann’s address to the German people in May 1941. We Americans are now in the same predicament.

***

I tell you at the moment of your greatest — or perhaps not yet greatest — exuberance, that it will not be accepted, not permitted. Do not believe that you only have to establish iron facts before which humanity will bow in due time. It will not bow before them, because it cannot bow before them. However scornful, bitter, and doubtful one’s thoughts may be about humanity, there is, underneath all wretchedness, a divine spark in it, undeniable and inextinguishable, the spark of the spirit and the good. Mankind cannot accept the ultimate triumph of evil, untruth, and violence — it simply cannot live with them. The world resulting from a Hitler victory would be not only a world of universal slavery, but also a world of absolute cynicism, a world which would find it totally impossible to believe in the higher and better in man any longer, a world which would belong completely to evil and be subject to evil. There is no such thing; it will not be tolerated. The revolt of humanity against a Hitler world filled with the utmost despair of spirit and good — this revolt is the most certain of all certainties; it will be an elementary revolt before which the ‘iron facts’ will crumble like plaster.

The desperate revolt of humanity against Germany – must it come to that? German nation, how much more must you fear the victory of your leaders than their defeat!