⬆︎ The Dan River along Kibler Valley Road, Claudville, Virginia

One of my New Year’s resolutions is to go on more photo-taking and hiking expeditions. Yesterday I explored the upper Dan River, on a quest to figure out where the river comes down out of the Blue Ridge Mountains into the foothills.

The Dan River is part of the Roanoke River basin, one of the river basins of the water-rich Blue Ridge Mountains. The river meanders down out of the Virginia mountains into Stokes County, North Carolina, and flows about two miles south of Acorn Abbey. The river meanders back into Virginia again (near Danville), then back into North Carolina again. It reaches the Atlantic Ocean through Albemarle Sound. Though Acorn Abbey, altitude about 1,000 feet, lies just south of the mountains, the fact that this area is in the same river basin really makes Acorn Abbey a part of the Blue Ridge. If you’ve heard Joan Baez sing “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” then you’ve heard of the area, when she sings, “Virgil Caine is the name, and I served on the Danville train.”

Though I know this area very well, recently I realized that I had no idea where the Dan River comes down out of the Blue Ridge Mountains (altitude about 3,000 feet at that point) into the foothills (altitude about 1,500 feet at that point). With a rapid 1,500-foot fall, shouldn’t there be some drama there worth seeing? What I learned is that the falls are no longer in their natural state. There are two dams on the mountain that hold back the water, sending part of the river’s water down a large conduit to a small hydroelectric plant built in 1938. The plant still supplies electricity to Danville, Virginia, which owns it.

⬆︎ The red dot shows the location of Acorn Abbey

⬆︎ Low-water bridge — no guard rails!

⬆︎ The headwaters of the Dan River lie in Meadows of Dan, Virginia. I know where roads cross the river, but I lost the river among the hills and valleys. So I stopped to ask at the Mayberry Trading Post where the river lies and where it falls toward the foothills. Speaking of Mayberry, if you’ve seen the Andy Griffith show, you might assume that the name “Mayberry” started with the television show. That is not the case. Andy Griffith grew up in Mount Airy, North Carolina. I believe he was descended from the Mayberry (shortened to Mabry) family of Carroll and Patrick counties, Virginia. Griffith chose the name “Mayberry” for the television show because of its local history and local color. My great-grandmother was a Mayberry/Mabry. This is where my roots are in old Virginia.

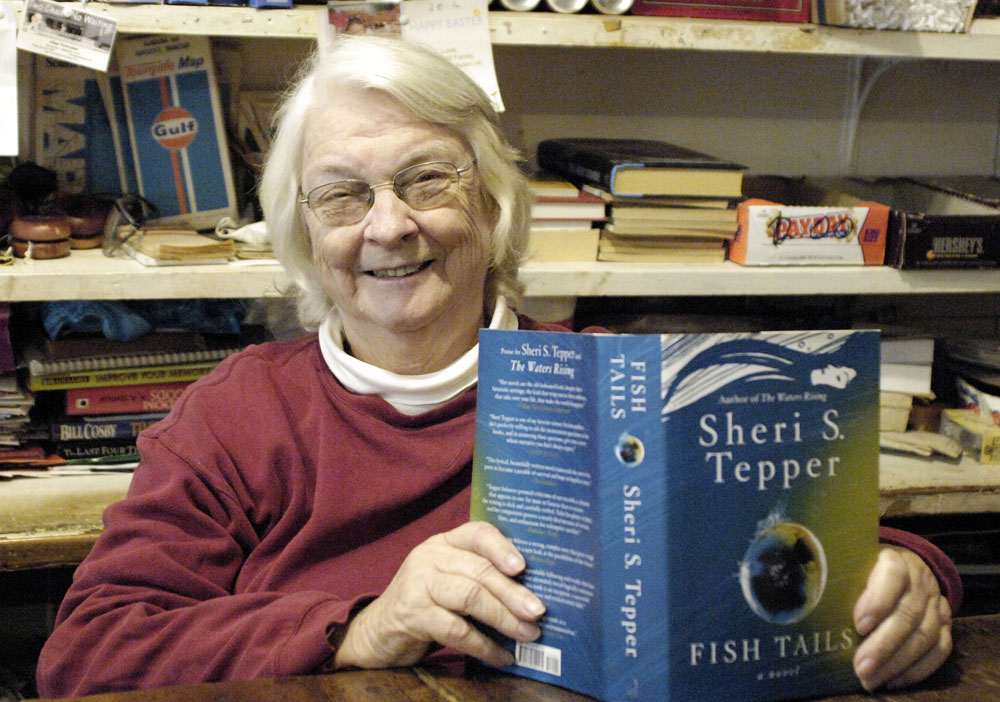

⬆︎ Peggy Barkley runs the Trading Post. She told me where to find the dams, and she told me how to get to the hydroelectric plant (which is far from obvious). Peggy is a great fan of science fiction. She was sitting at the counter reading when I went into the store. I asked her to hold up the book and show us what she’s reading.

⬆︎ I couldn’t get to the dam, when lies about a mile below this gate. So I headed down the mountain via Squirrel Spur Road.

⬆︎ Looking south from Squirrel Spur Road

⬆︎ Mayberry Presbyterian Church

⬆︎ Along the road to the lower dam

⬆︎ Mayberry Presbyterian Church is now on the National Register of Historic Places. The church was built by an intinerant preacher.

⬆︎ Looking down into Kibler Valley from Squirrel Spur Road

⬆︎ Squirrel Spur Road

⬆︎ Squirrel Spur Road near Meadows of Dan, Virginia, looking down into Stokes County, North Carolina. The low mountains are the Saura mountain range. That’s Pilot Mountain on the right, which Andy Griffith called “Mount Pilot.”

⬆︎ A river-bottom pumpkin patch near Kibler Valley, Claudville, Virginia

⬆︎ Tiny house on Kibler Valley Road

⬆︎ Kibler Valley

⬆︎ Kibler Valley

⬆︎ A section of the conduit that brings water down from the dams to the power plant

⬆︎ I understand that this telephone still works, though it’s not much used anymore. It rings up the mountain to the dams.

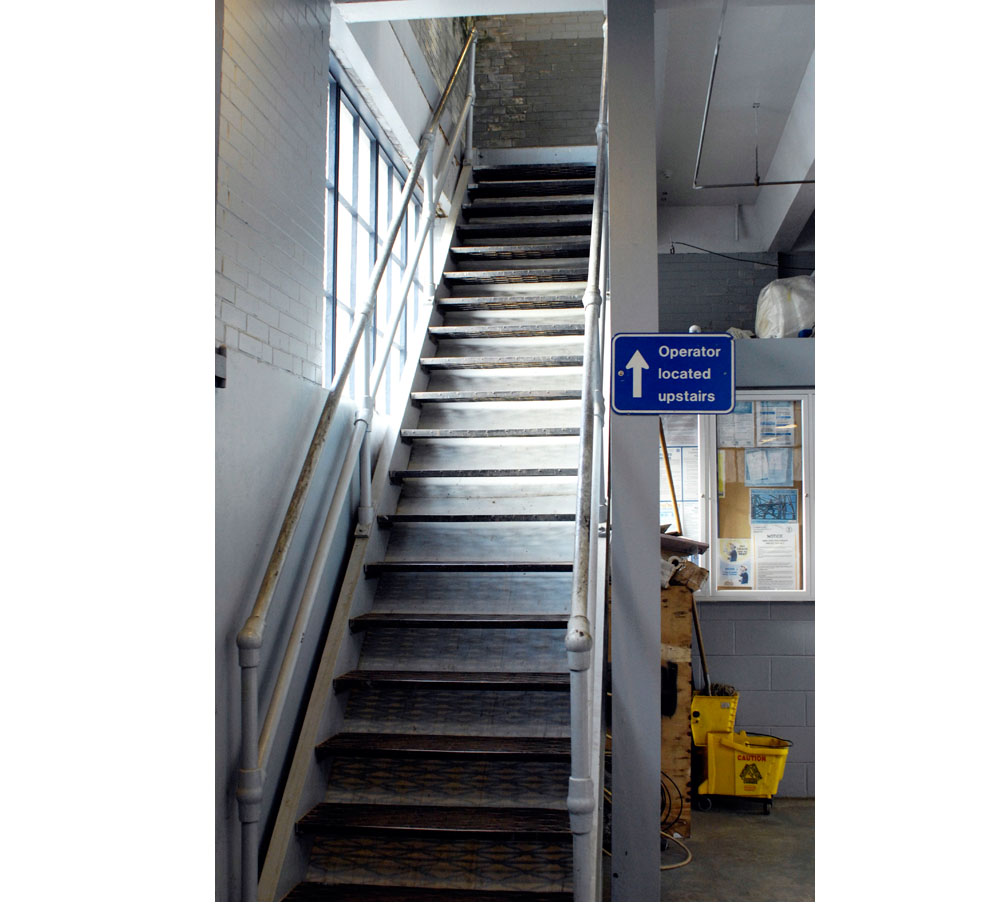

⬆︎ Tommy MacAdams, the operator who was on duty when I was there

⬆︎ On the way up the mountain, I had breakfast at the Cafe of Claudville in Claudville, Virginia.

⬆︎ On the way down the mountain, I stopped at the Cafe of Claudville again, for supper. This is salmon cakes and fixin’s.

All the photos are digital, shot with a Nikon D2X with a 28-85mm lens, except for the food shots, which were shot with an iPhone.