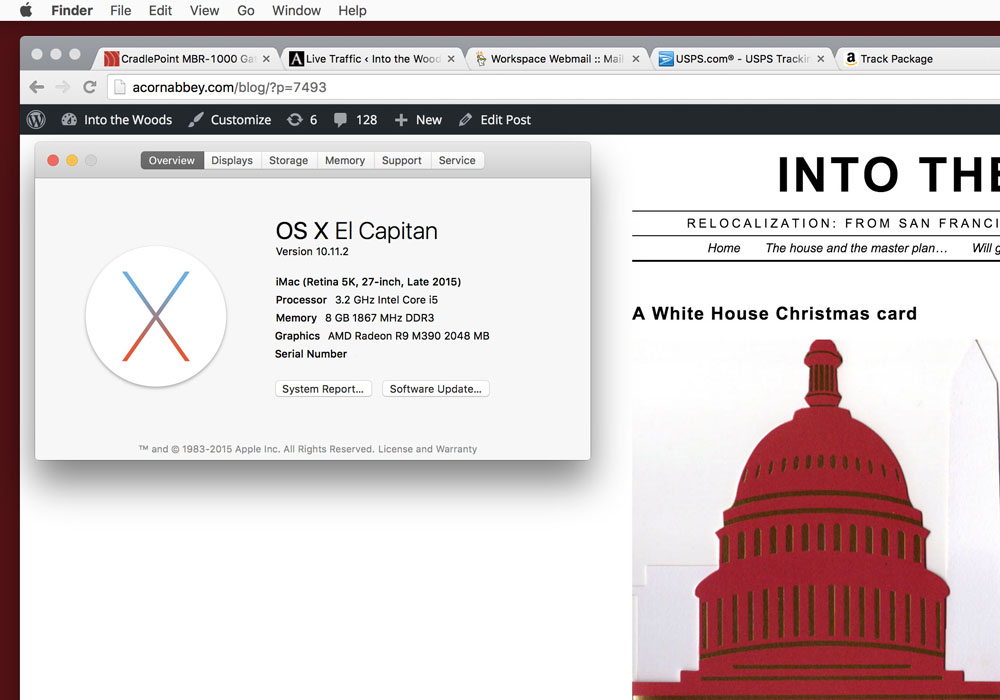

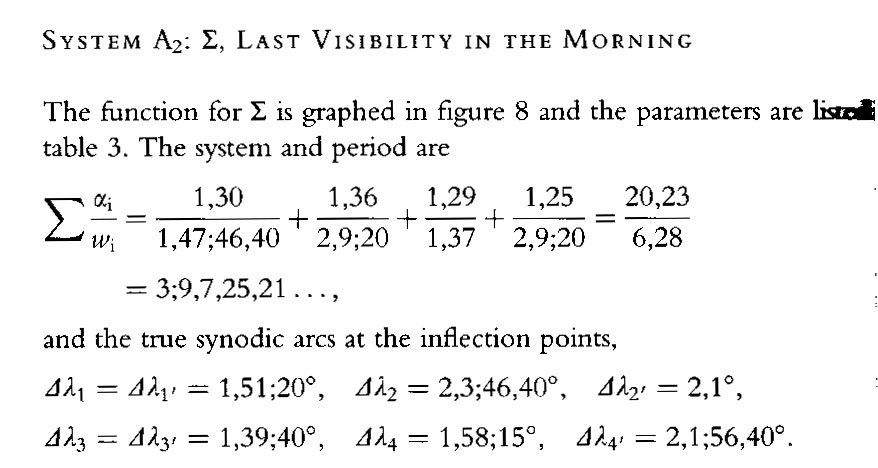

iMac (Retina 5K, 27-inch, Late 2015)

My old iMac was dying. It was eight years old and had served me well — no glitches, no grief, no fuss, no drama. But hard disks can’t last forever, and its hard disk was dying. The old Mac had started to limp — freezing and making racheting noises as the hard disk tried to read bad sectors. The old Mac is fine except for the dead disk. Sometime soon I will open it up, replace its hard disk, and it will live again as a backup computer. iMacs are not cheap, but in the long run they’re a bargain. I got my money’s worth, and then some, out of that Mac.

The new iMac is a 27-inch model with the Retina 5K screen, built in late 2015. It has eight gigabytes of memory and a 1 terabyte fusion drive.

I had considered buying one of the new 21-inch iMacs with the Retina screen, but the high-end reviews recommended against the 21-inch iMac in favor of the 27-inch iMac. For one, the price difference isn’t all that great. For two, the 21-inch models are a generation behind with the Intel processors. For three, the 21-inch models are not expandable. Their memory is soldered in, so you can’t change or add memory chips. For four, the 21-inch model has a slower and inferior graphics controller. So, for the few extra hundreds of dollars, you get not only a much bigger screen with the 27-inch models, you also get better internal hardware.

What I like:

• The screen is enormous! The clarity of it is incredible. At 227 pixels per inch, it’s impossible to see individual pixels. Black type on a white screen looks like fine printing on glossy paper, nicely lit. This monitor also has a larger color gamut than earlier LCD monitors, meaning that it can display a wider range of colors.

• It’s fast. My old iMac was pretty slow by comparison, especially when starting up applications or while paging through a lot of photographs. The fusion drive in the new Mac is probably a major factor in permitting most apps to start up in less than a second.

• Migration was easy. I used Apple’s Migration Assistant application. I had made regular backups of my old iMac onto an external hard disk, so Migration Assistant pulled all my files in from the backup disk. That took about 45 minutes. Then, when I first logged into the new iMac, all my stuff was there — mail, photos, bookmarks, and documents.

• The sound quality is remarkable. They seem to have made the whole computer into a speaker cabinet. There’s a little too much resonance (a little like the acoustics of a bucket), but the bass response and overall sound quality are much better than my old iMac.

What I don’t like:

• The keyboard that comes with the new iMacs is small and hard to use. The keyboard does not have page up/page down keys (which I use all the time). Even worse, to save space, the up-arrow and down-arrow keys are actually merged into a single key — half a key each. I have no idea who designs Apple keyboards. They seem to think that laptops now set the standard for keyboards. I despise laptops, not least for the keyboards. The keyboard that comes with new Macs, a Bluetooth keyboard, has no USB ports on the sides. So I went back to my nice, wide extended keyboard.

All in all, the new 27-inch iMac is a magnificent piece of hardware. I hope it will last eight years like its predecessor.

Macintosh OS X 10.11.2 (El Capitan)

El Capitan looks and behaves pretty much just the same as the previous version of OS X, Yosemite. In the previous couple of OS X updates including Yosemite, Apple concentrated on getting OS X to interact smoothly with iOS (iPads and iPhones). In El Capitan, like it or not, Apple seems to be concentrating on internal changes in the operating system to make it more difficult for rogue software (and dumb users) to screw things up. In iPads and iPhones, iOS prevents you from getting under the hood at all. In OS X for iMacs and laptops, you can still get under the hood. But, increasingly, Apple is limiting what you can do (unless you really, really know what you’re doing).

It’s easy to understand why Apple is doing that. They have millions of devices in the field. Apple’s reputation depends upon those devices working properly. But users are highly inclined to do stupid things, and there are criminals and predators all over the Internet trying to hijack every device they can and install their malware on it. When Apple makes these kinds of changes that shut you out of your own computer, they always talk about security. But I suspect that a bigger issue than Internet security is keeping owners of Apple devices from monkeying with things, and making it harder to install crapware.

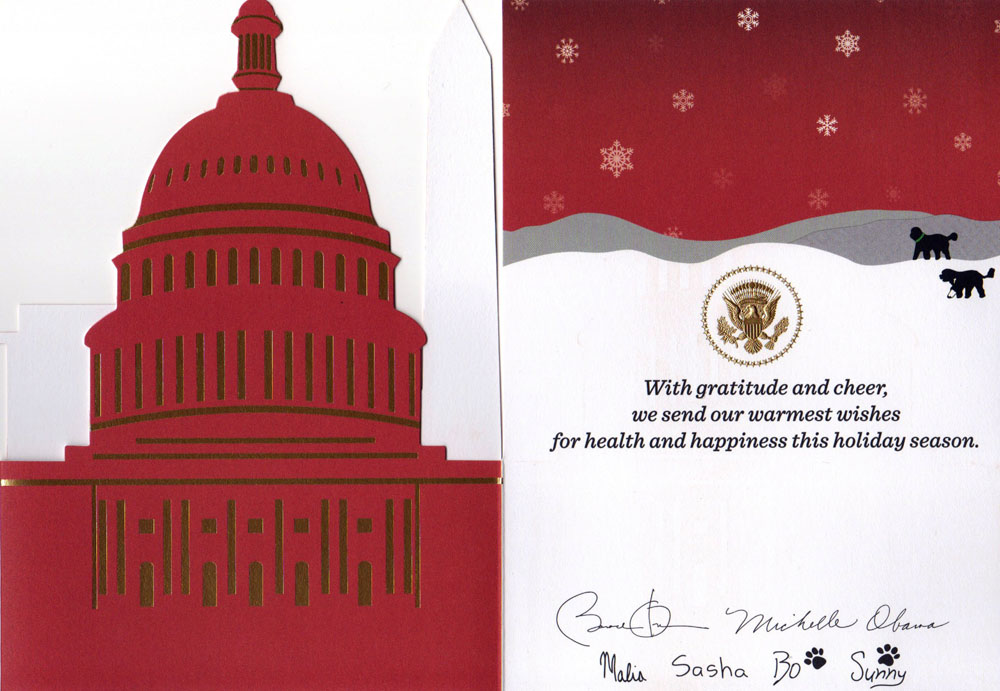

Before I went to the Apple Store to buy the new iMac, I looked up the address and hours on line. Google also showed me customer reviews and customer ratings for the Greensboro Apple store. There were lots of angry, one-star reviews. A typical one-star review might come from an iPhone user whose iPhone was giving trouble. This user would go to the Apple Store irate, blame Apple for whatever was wrong, and demand that the problem be fixed right there on the spot, right this instant. If that didn’t happen, they wrote a one-star review.

Over the years, the advice I’ve always given to people about keeping their computers running smoothly is not to install a bunch of crap on it. Most of the time, when something goes wrong, it’s because of a crap app. In El Capitan, Apple has new safeguards to keep crap apps out. For one, Apple wants signed certificates in software now that identify the software developer and the develop’s good standing with Apple. For two, it used to be that with the “root” password, or system password, you could tinker with any part of the system on an iMac or laptop. In El Capitan, “root” no longer has absolute privilege. There’s another layer of protection that keeps owners — and software — sandboxed to limit the damage that can be done. I have mixed feelings about this. On the one hand, as a veteran Mac user (since the 1980s!), I want to be able to do whatever I want to a system that belongs to me. On the other hand, less experienced users, when they (or a crap app) screw things up, they think it’s Apple’s fault and expect Apple to fix it for them.

It’s sad, in a way, to see an Apple store getting so many bad reviews for customer service. But is there a Microsoft store in your town? Can you walk into a Microsoft store, step up to a bar, and get a Microsoft “genius” to work on your device? Can you even call Microsoft on the phone? Of course not. Even if the Apple stores are packed, and even if you have to wait for someone in a red shirt to help you, at least Apple is there. When you buy a new iMac, you get 90 days of free “Apple Care” in addition to the one-year warranty. A lot of one-star reviews from angry iPhone users does not necessarily mean that Apple is bad at customer service.

My big concern is about how quickly these restrictive updates in Apple’s OS X cause older software to stop working. I absolutely depend on the Adobe Creative Suite, which includes Photoshop and, for publishing work, InDesign. I have version 5.5 of this Adobe software, which is one of the last versions that you can actually own outright. These days, Adobe sells this software in “cloud” versions for which you buy a “subscription” and pay for the software monthly or annually. You don’t own the software; you just rent it and keep on paying. Sooner or later, because Adobe no longer supports or updates Creative Suite 5.5, a new OS release from Apple will break the Adobe software, and I’ll be up the creek. But, so far, Photoshop and InDesign seem to work OK with El Capitan.

OS X El Capitan: The Missing Manual, by David Pogue. O’Reilly Media, 846 pages, November 2015.

Do you need this book? Probably not, not unless you’re at least a bit of a nerd, and if you have limited experience with Macintoshes, and if you’d like to do more with your Mac. At 846 pages, I wanted this book to get more under the hood and describe the mysterious inner workings of Apple’s OS X operating system. But that’s not really what the book is about. It’s about the kind of stuff that regular Mac users might want to do. If you’ve been using Macs for years, then much of what’s contained in this book is stuff that experienced Mac users “just know.”

Personally, I’m curious about the inner workings of Macintoshes. OS X has changed significantly in the past few years. I have been a Unix user since 1984. Unix, for years, has been my preferred operating system and the operating system that I’m most comfortable with. That’s one reason I use Macintoshes — they’re Unix boxes, under the hood. Apple, however, has taken Unix in a direction very unlike where Linux (now in many flavors) or Sun’s (now Oracle’s) Solaris has gone. Without some documentation, it would be pretty near impossible to see what changes Apple is making in the Unix system that lies under the graphical user interface.

To really know what’s going on under the hood, you’d need to see documentation of the type that software developers use. You’d have to get it from Apple, and I assume you’d have to sign a nondisclosure agreement. But for a technical overview of what’s under the hood in El Capitan, here’s a link to a 40-page “white paper” from Apple.

On the other hand, if you’re a person who can learn from books, and if you’re a little afraid of your Macintosh and would like to become better acquainted with it, then Pogue’s book is probably the best book that you can get on the subject. There are lots of illustrations to show you what you should see on the screen. There’s a good index. The book is nicely organized. And there’s an appendix on troubleshooting.

With books like this, you just might be able to solve some of your own Mac problems without standing in line at the Apple store.