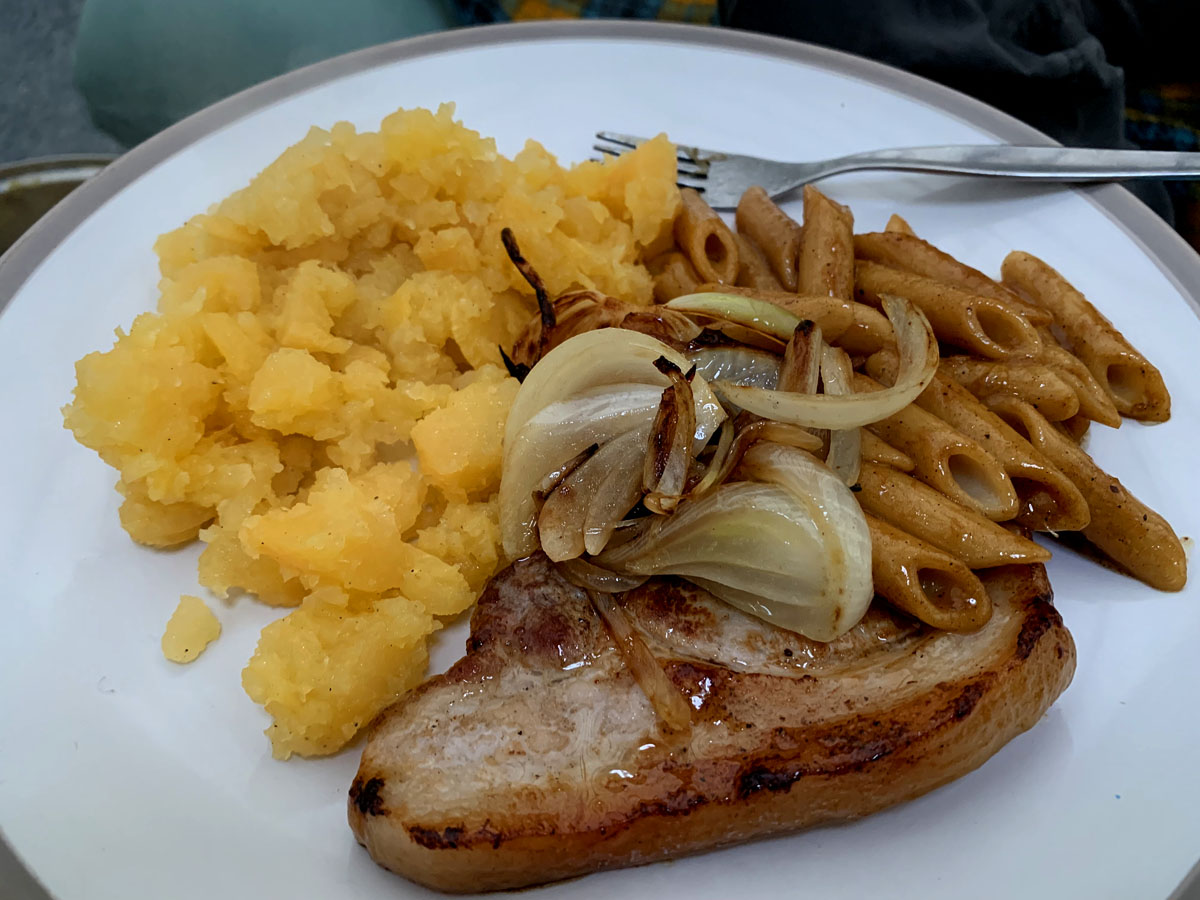

Chaser. Wikipedia photo

A few days ago, the New York Times carried an obituary for a dog. The dog was Chaser, a border collie who was taught to understand 1,022 nouns. Here’s a link to the story:

Border Collie Trained to Recognize 1,022 Nouns Dies

I often wonder if I should be ashamed of my own thoughts. My thoughts in this case were that, in many cases, it is perfectly reasonable to value the life of an animal as much as the life of a human being. And — let’s admit it — we value the lives of some animals more than the lives of some human beings. Not everyone gets an obituary in the New York Times, but this dog did.

You may remember back in 2015, when Cecil the lion, a much-loved resident of a national park in Zimbabwe, was murdered in cold blood by an American big-game hunter. As outrage and grief poured out in social media, the usual small-minded moral scolds went to work, berating people for being concerned about the life an animal when so many people … [fill in the blanks with their personal cause]. I was so irked that I posted here about that at the time, with the argument that it is perfectly possible to have more than one moral concern at the same time.

One of the most mysterious subjects in metaphysics and biology is consciousness. We don’t know what consciousness is or where it comes from. But, one hopes, we have laid to rest the idea that animals are different from human beings in any essential way. They are just as conscious. They have a full range of emotions, just as we do. They love just as deeply. They are greatly troubled by fear and worry. They love their lives. The differences between human DNA and animal DNA are trivial.

Ask your average witless Christian whether animals have souls, and the answer will be that of course animals don’t have souls, that only humans have souls. Witless Christians who are more theologically inclined may then say something about how God gave us humans the fruits of the earth, to “harvest” as we please. That’s dominionism, one of the ugliest theologies there is. They actually apply the word “harvest” to animals.

But if the question of souls, whatever souls may be, is inherent in the nature of living things, as opposed to some magical ontological theological notion about which ancient and ignorant religionists knew more than we do, then it seems safe to assume that animals are not different from us in any essential way. If we have souls (a question I think we cannot answer), then they do, too. Consciousness suffices. Simply to be a living, feeling being is to have rights and claims on fairness.

According to the New York Times story, not only did Chaser know 1,022 nouns, he also understood sentences containing a prepositional object, verb and direct object. Chaser was able to learn so much language because border collies are a very smart breed and because his owner spent many, many hours teaching Chaser language. But everyone with a dog or cat knows that every dog and every cat learns enough language to manage daily routines. The more you talk to your dog or cat, and the older your pet gets, the more language your pet will learn.

My cat, Lily, now eleven years old, used to be terrified of the abbey organ because the organ can be quite loud. But after a while she developed a new routine whenever the organ is played. She goes to a table facing the organ console and watches. I soon learned that, if I play quietly, she likes the music (a collie I once had used to come and lie under the piano any time I played). And then I learned that Lily has a favorite song. That song is “Danny Boy,” which I play quite softly with velvety stops and tremulant, adding in some soft reed stops as the song develops. A couple of months ago, after I had played “Danny Boy,” I got up from the organ, and Lily was crying. She came to me, bumping her head against me, very emotional, crying the same way she had cried after I returned home from two weeks in Scotland. She understands, I believe, what that song means. It is a song about loss and grief, with the hope of reunion in some unknown world. The song expresses a feeling — a condition of the soul, if you will — and I believe that Lily understands that feeling just as well as we humans do. Because music is a universal language, she knows what “Danny Boy” means.

In John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice, a book that I have mentioned here often, Rawls does not take up the issue of animal rights and fairness to animals. But he practically begs someone to do that work, which mostly remains undone. If you are familiar with Rawls, then you’re aware of his concept of “the original condition,” in which we arrange the world as though we can’t know before we come into this world what our circumstances will be — male, female, black, white, rich, poor, beautiful, ugly, smart, dumb. We would want the fairest possible world. It’s not at all difficult to add another condition to Rawls’ thought experiment. What if we didn’t know whether we would be born human or animal? Whether we were a wild animal, or a farm animal, or somebody’s pet, would make no difference.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we were the kind of society in which, in a presidential debate, we could talk about fairness for all living things, rather than the usual agenda based on increasingly mean and increasingly cruel right-wing talking points.

The Rawls thought experiment is incredibly easy to apply to animals. Talk to a chicken, a cow, a lion, a dog, a bird, a whale. Ask them what they want, and what they would consider fair. You know what they would say.