Hugh Jackman in “Oklahoma,” broadcast yesterday on WUNC-TV

One of my regular themes on this blog is beating down the misconception that digital technologies have made radio obsolete. The opposite is true. Digital technologies have made radio more important than ever. I am, of course, using the broad definition of radio — the wireless transmission of information using the electromagnetic spectrum. Your WIFI router, your cell phone, your car keys — all of them contain radio apparatus, and they all use some part or other of the electromagnetic radio spectrum. By this definition, even television is radio. It’s just that the radio signal used by television is modulated in such a way that it can create an image.

The important thing to know here is that there is only so much radio spectrum, and that there is not enough of it. The only way to manage this limited resource is to regulate the living daylights out of it, and to manage the spectrum wisely and frugally and in the public interest, because radio spectrum is a publicly owned natural resource. That’s what the FCC is for.

Most people get their television these days by connecting to cable or satellite. But about 10 percent of Americans — including me — either can’t or won’t pay the high cost of cable or satellite and get television over the air, through an antenna. This is on my mind right now because I finally was able to find a low-cost antenna ($40), that when placed in my attic and pointed toward Sauratown Mountain can pick up the nearest PBS television station. Up until now, the abbey’s rarely used television (except for watching DVD’s and Blu-ray) has not been able to receive PBS.

I’m not going to get too nerdy on this point, but because I have a strong interest in radio communications and because I have an Extra class amateur radio license, I’m very familiar with radio spectrum and how radio waves propagate differently according to their frequency. Most people, of course, don’t care in the least what frequency their cell phone is using. But we nerds care, and given a particular device we probably can tell you pretty precisely what frequency or “band” it is using. Depending on who your carrier is and whether we’re talking about voice or data, your cell phone is using UHF frequencies between 800 Mhz up to about 2500 Mhz.

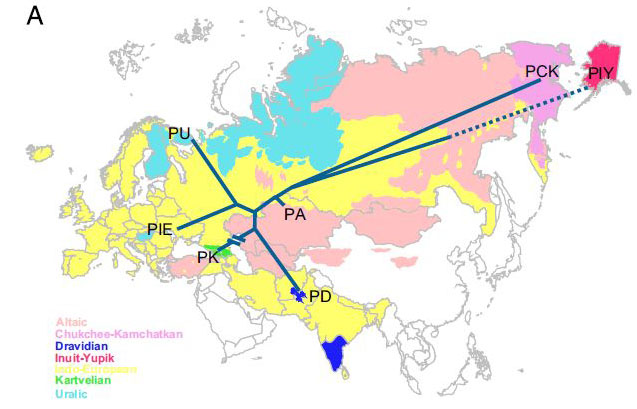

The UHF television channels (channel 14 through 69) range from about 470 Mhz to 800 Mhz. This is very valuable radio spectrum, and big players like Verizon want as much of it as they can get. There is no plan at present, as far as I know, to completely toss out broadcast television. But the FCC is working on taking back television spectrum and freeing it up for wireless data.

This is not a bad idea, though I’m always wary when so much money and corporate intrigue are involved. Because radio waves of different frequencies propagate differently, there are some advantages to television vs. cellular frequencies. The lower television frequencies penetrate buildings better and can travel farther. Cellular towers wouldn’t have to be so close together. But because the frequencies are lower, antennas also need to be longer to be efficient. Television frequencies are ideal for devices that are in a fixed location with a larger antenna — for example, in your attic rather than in your pocket. That’s why television ended up on those frequencies in the first place — wisdom and technical savvy exercised years ago by the FCC.

I mentioned that the PBS station nearest to me is on Sauratown Mountain, about 18 miles away. The right technology sitting on that mountain, using television frequencies, would be ideal for finally getting true broadband into a bandwidth-deprived rural home like mine.

Will it happen? First the FCC has to get it right. Then someone has to step in and build the infrastructure. Personally I would like to see a publicly owned, nonprofit system using this spectrum and providing broadband to rural homes and businesses at a reasonable cost. But corporations hate this idea, because the few publicly owned broadband systems in the country are delivering data much faster and cheaper. In North Carolina, corporations even lobbied for, and got, a state law that all but eliminates competition from publicly owned systems. And yes I’m still angry about this, because it shows how easily politicians can be corrupted into serving profit rather than the public interest.

Our job is to keep a close eye on what the FCC is doing and make sure that the public interest is served. Most people don’t realize that the radio spectrum is owned by the public. It is a natural resource, and it is scarce and limited. That’s why it can’t be used without a license, and that’s why it must be closely regulated to prevent misuse and interference. If we don’t keep an eye on the FCC, they’re all the more likely to sell out to profit and betray the public interest. Yes, we “auction” radio spectrum and permit it to be used for profit, but that right always comes with a license and strict terms. There’s always a way of taking the spectrum back if the terms of the license are violated. The radio spectrum ultimately does not belong to Verizon or to any other corporation. It belongs to us.

Now back to PBS for a moment. One of the needs that PBS ought to be serving is keeping the public aware of issues like this. Lord knows the local news won’t. But as far as I can tell, WUNC-TV — North Carolina’s public television system — is letting down on the job. Of course, their budget has been blown apart by the current regime in Raleigh, which I believe prefers that the public be kept in the dark. It appears to me that most of WUNC-TV’s state-produced programming has been heavily featurized and dumbed down. One of this blog’s regular readers is an academic who specializes in this area, so maybe he can comment on the current state of WUNC-TV’s public affairs programming.

An afterword about why regulation is not a violation of individual rights but is absolutely critical: Anyone who holds an amateur radio license is aware of the terms of that license and what kind of violations would cause the FCC to revoke the license. If I tried to use my license to broadcast, as opposed to talking to one other station, I would lose my license. If I repeatedly tried to use the ham bands for political speech or profanity, I would lose my license. If I accepted money for anything I transmitted on the ham bands, I would lose my license. If I got caught even once transmitting on a frequency that I am not authorized to use, I would lose my license. (Try transmitting on a frequency used for law enforcement and see how fast the FCC hunts you down and throws the book at you). If I interfere with another ham radio operator’s lawful rightful to use our frequencies according to the legal terms under which we share those frequencies, I would lose my license. If the use of the radio spectrum was not closely regulated, all your devices that depend on radio, including your GPS device, your cell phone, and the navigation systems of the airplane you’re on, would become unreliable, because there would be no legal means of preventing interference and abuse. I can’t resist getting in the occasional dig at “libertarians.” Mostly, they’re crazy.