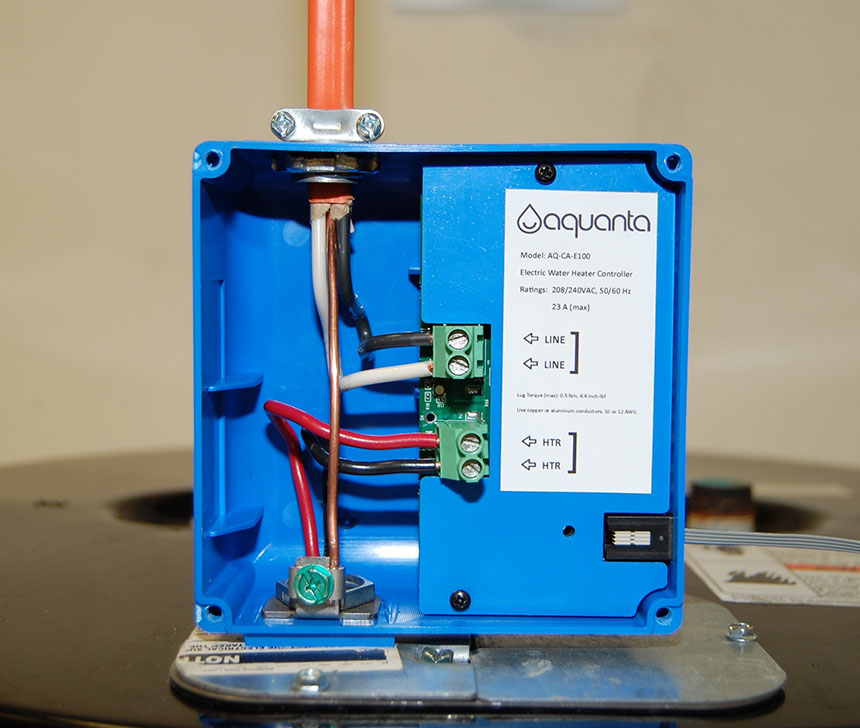

The insides of an Aquanta water heater timer.

I received a letter from my electric company saying that, starting April 1, they will be switching to a peak demand rate plan. If you’re not already on such a rate plan, you probably will be soon.

Both the letter I received from the electric company, and the information on their web site, was irritatingly vague. It took some time for me to figure out how the peak demand charge is calculated each month. I won’t try to explain it here because the rules will vary from electric company to electric company.

My electric company, Energy United, is a small regional co-op. I tend to trust them more than I would ever trust the energy giant in this part of the country, Duke Energy. Still, a co-op that doesn’t generate any power itself must buy it, and I assume that Energy United buys primarily from Duke Energy. I assume that Duke Energy charges Energy United more for electricity during peak demand times.

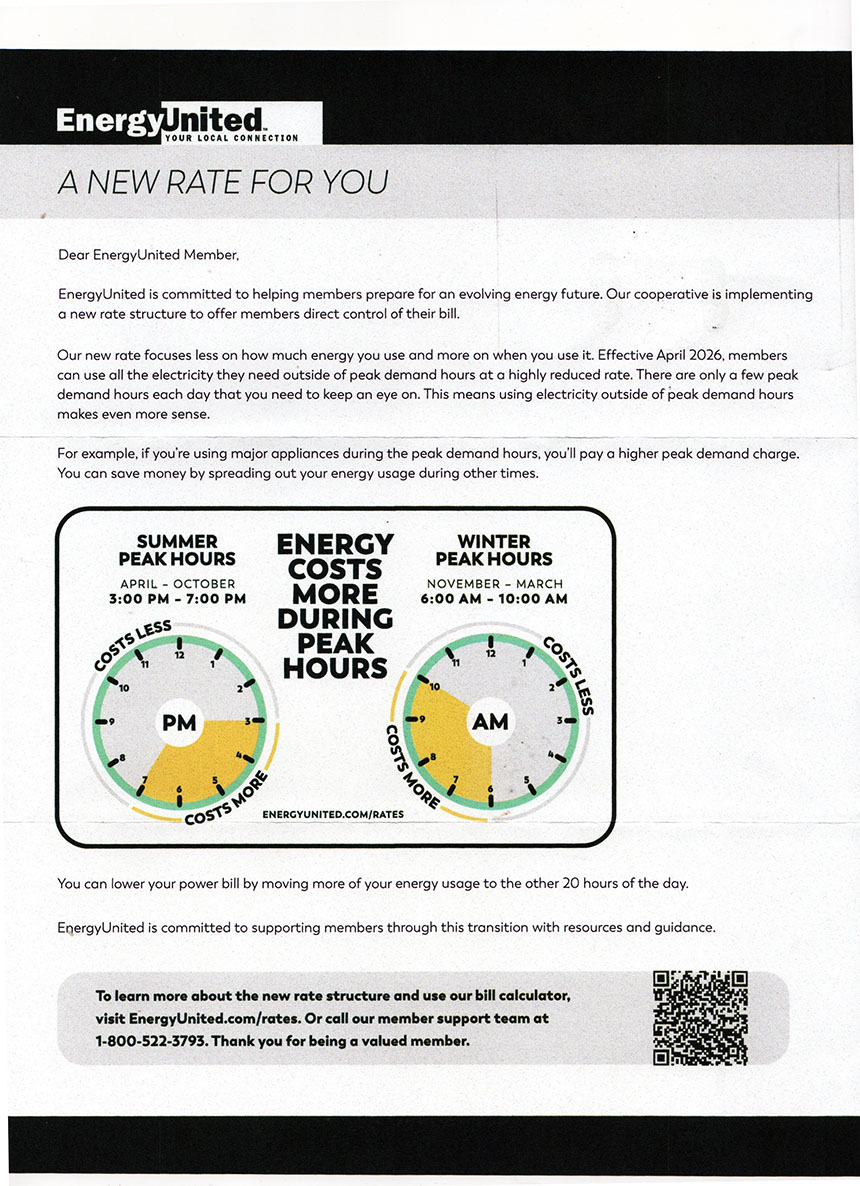

The marketing angle is that peak demand pricing “gives you direct control of your bill” and can save you money. Is that true? It’s possible, but only if you avoid pulling a lot of power during peak demand times — winter mornings and summer afternoons.

That won’t necessarily be easy. Winter mornings between 6 a.m. and 10 a.m. is when most people are up, re-warming their houses, and making breakfast. And summer afternoons between 3 p.m. and 7 p.m. is when cooling systems work the hardest and people are home from work and making dinner.

Some electrical usage is optional, and some is not, of course. Obviously it would be a bad idea to run a clothes dryer during peak demand time. To some degree, we can manage heating and cooling with our thermostats.

Small electric loads such as lighting or televisions won’t add much to your peak demand. The biggies are heating, cooling, dryers, ovens, and water heaters. If those big loads all run at once, your peak demand could be very scary.

Electric water heaters use a lot of power. If a water heater switches on during peak demand times (as is very likely), it will add about 5,000 watts (5 kW) to your peak demand. I estimated that, given my electric company’s rates, if my water heater switched on even just once during the monthly billing period during peak hours, it would add $22 to my bill for that month. Getting control over the water heater is an obvious way to save money. A water heater timer would soon pay for itself.

After talking with the plumber who replaced my water heater a couple of years ago, I decided to install an Aquanta “smart” water heater timer. Amazon has them. They’re not cheap ($164), but the older mechanical timers seem too unreliable and inaccurate. The Aquanta timer can be monitored and controlled from a phone app or from the Aquanta web site.

These new rates seem pretty unfair to working families who don’t have much choice about when they use electricity. For retired people like me, it’s easier. When the new rate scheme kicks in, I’m guessing that a lot of people who weren’t paying attention to the change are going to be shocked when they get their first bill.

Still, it’s entirely rational that electric companies are moving to rate plans that factor in when you use electricity as well as how much electricity you use. Nationally, peak demand is growing faster than overall usage is growing. Yes, AI data centers have something to do with it.

For what it’s worth, here is the letter from my electric company. It’s mostly marketing language, leaving it up to you to figure out how you will be affected by the new rates. Click here for high-resolution version.