The Tristan Chord: Wagner and Philosophy. By Bryan McGee, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 2000.

When I bought this book, I expected only to browse it. I ended up devouring it. As I’ve mentioned in other posts, you never know where research for a novel might lead you. In this case, I was thinking about musical metaphors and interesting ideas for the Socratic dialogues in Oratorio in Ursa Major.

Truth be known, I am not that great a fan of Richard Wagner. I even have been to a performance of “Tristan and Isolde” by the San Francisco Opera, and that did not win me over to the music. I find the music (four hours of it!) difficult to listen to. Still, the legend of Tristan and Isolde is archetypal in Western culture. Jake, my protagonist and hero in Fugue and Oratorio in Ursa Major, often makes drawings of unusual buildings, and he has a bit of a thing for towers covered with vines and thorns (like the tombs of Tristan and Isolde in some tellings of the story).

Nevertheless, I think it’s very important to know just what a landmark Wagner’s “Tristan and Isolde” was in the 19th Century. The music was like nothing ever heard before. Orchestras declared it impossible to play. Singers said that it was impossible to sing. There were more than 70 rehearsals of the opera in Vienna between 1862 and 1864, but the performance was called off and the opera was declared unperformable. Finally Wagner succeeded in staging it, in 1865 — 150 years ago.

After 150 years, the debate still runs hot in some musical circles. Just what is Wagner’s Tristan chord? Is it just a modified minor seventh chord? Or is that G-sharp an appoggiatura to the A, putting the chord in a whole different light? (It’s not necessary to understand the music theory here. The point is that the experts have been arguing and disagreeing for 150 years, and there are several theories about what the chord is.)

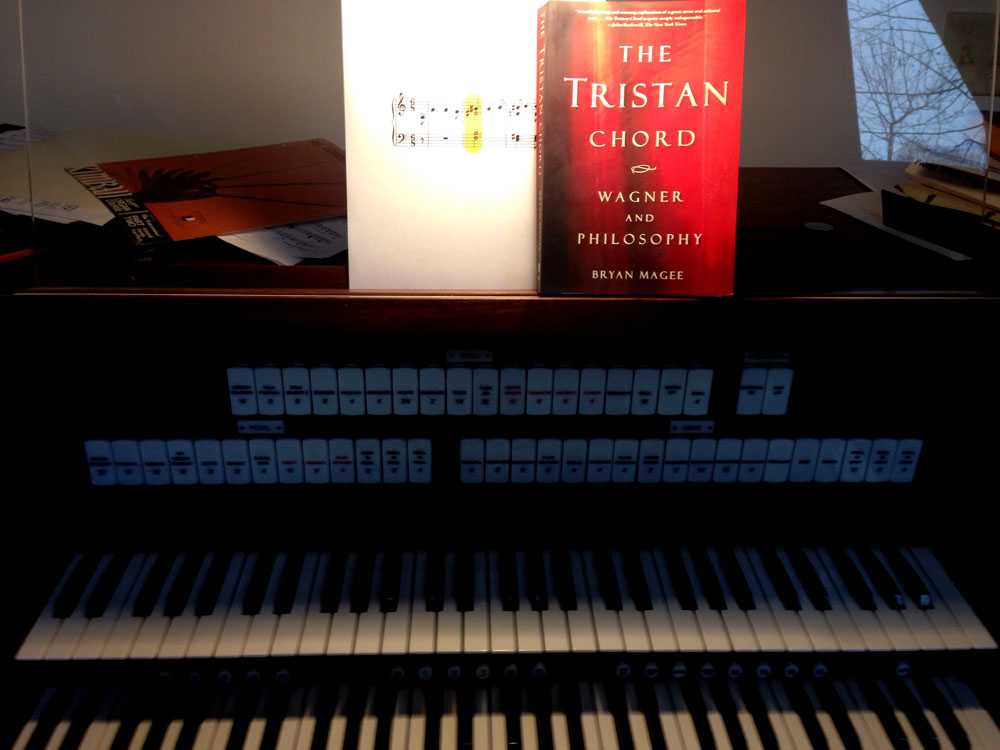

Here is what the music looks like:

Here it is played on the Acorn Abbey organ:

Stephen Fry did an excellent documentary on the Tristan chord called “Wagner and Me” back in 2010. (More about this Fry documentary in a moment.) Fry emphasizes the unbearable longing that the chord expresses. Our ears want the chord to resolve, but in four hours of music, it never does — not until the very end of the opera. No wonder some people consider the opera to be torture.

What do we mean by a chord resolving? Even if you can’t read music and don’t know a thing about music theory, your ear knows all the rules. For example, if I sing the first line of this ditty:

Old MacDonald had a farm!

Your ear will give you no rest until you hear that musical phrase resolved:

Eee-aye eee-aye oh!

There. That resolved it. Or think of the last note of pretty much any song:

And crown thy good

With brotherhood

From sea to shining —

Your ear will give you no rest until you hear the last note, in which the dominant chord, as it always must, resolves to the tonic:

Sea!

Believe me, even if you think you know nothing about music, if you love music and listen to music, your ear knows all the rules. I doubt that any metaphysical system will ever be able to explain why music has the emotional effect on us that it has, but part of that musical effect, surely, is creating tension — even longing — in unresolved harmonies and melodies, and then taking us along for a nice ride toward the resolution.

In many ways, John Williams (who wrote the music for “Star Wars”) is the Wagner of our time. Listen to this performance of Leia’s theme and think about how the music creates longing and tension and demands that we listen until we hear these tensions resolved. The final resolution comes quietly at 4:11, with a lonely note from the violin, followed by the remainder of the tonic chord in an arpeggio from the harp. Again, it doesn’t matter what the “tonic” chord is or what an “arpeggio” on the harp is. Your ear knows when it has finally got what it wanted. When the final chord finally comes, the orchestra quietly takes over the chord from the violin and the harp and holds the chord for many beats, to let the resolution sink in and to give our ear the peace it was longing for:

You’re not in a hurry, are you?

Here’s an excerpt from Stephen Fry’s “Wagner and Me” documentary:

Part of what makes Bryan Magee’s book so fascinating is his discussion of the philosophy of Immanuel Kant and Arthur Schopenhauer, both of whom greatly influenced Wagner. Over the years, I have made repeated attempts to read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, and each time I have been turned back by the impenetrable density of Kant’s writing. Magee acknowledges that Kant’s writing was unnecessarily turgid and boils Kant down. We are all Kantists now. Magee does the same thing for Schopenhauer. And thus I learned that I am pretty much a Schopenhauerian, though not quite as pessimistic.

Magee is an engaging writer and has written a number of books aimed at making modern philosophy comprehensible to ordinary people.