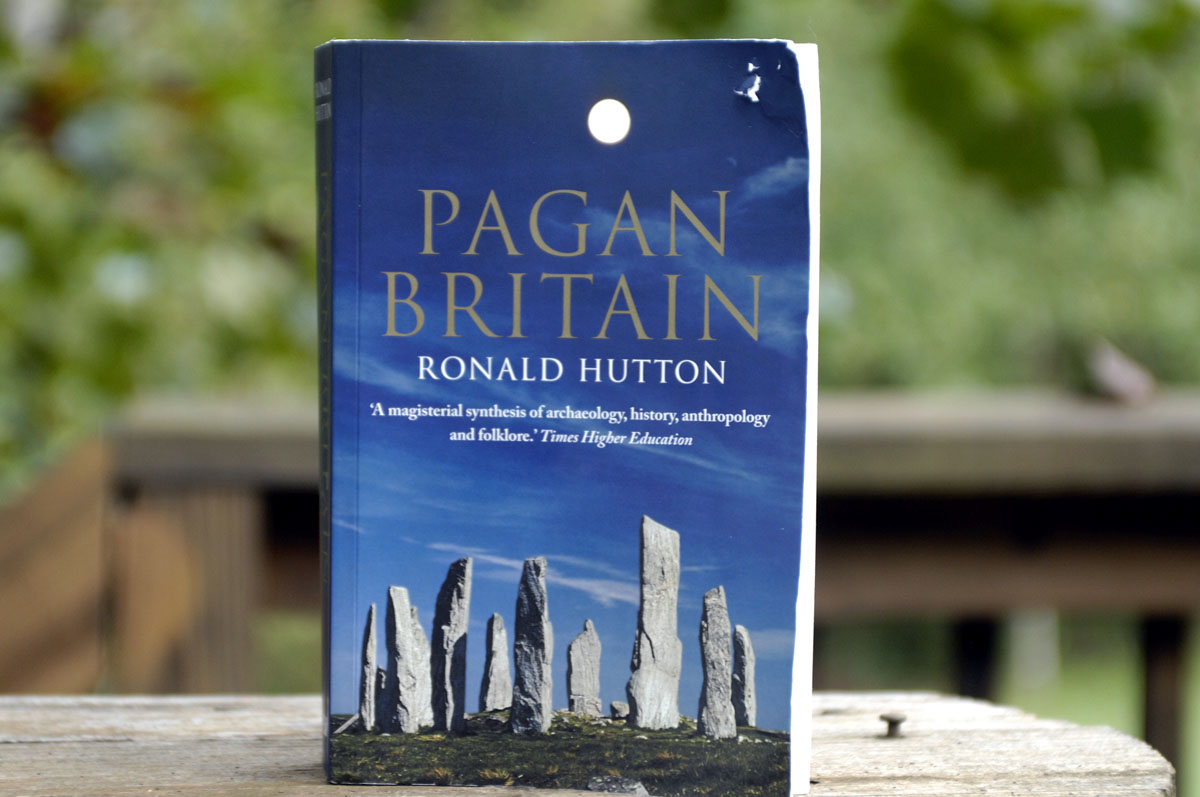

Pagan Britain, by Ronald Hutton. Yale University Press, 2013. 480 pages.

If you plucked this book down off a bookstore shelf to have a closer book, you probably would assume from the cover and the title that the book is a romanticized effort to find magic in Britain’s past. That assumption would be wrong. If anything, the book is the opposite of that. Instead, the book is a thorough analysis, based primarily on archeology, of how any genuine understanding of Britain’s pre-Christian past is impossible.

The author is a professor of history at the University of Bristol. The blurb on the cover of the paperback edition sounds promising, quoting Times Higher Education: “A magisterial synthesis of archeology, history, anthropology, and folklore.” Unfortunately, that is misleading. The book is magisterial, but the book is 99.9 percent archeology, simply because where history and folklore are concerned, almost nothing remains, whereas the archeology is extensive. The author refers to textual classical sources where such sources exist (for example, Caesar’s account of the Gallic wars). But all those classical sources must be taken with a grain of salt because they were often second- or third-hand or were written long after events occurred. Later sources, such as the Venerable Bede’s An Ecclesiastical History of the English People, was written hundreds of years after events occurred and must be read as hopelessly biased by Bede’s religion. In short, such written records as exist are extremely unhelpful.

It has often been supposed that, during the Middle Ages, the Christian religion was a thin veneer over still-pagan rural cultures in which the old ways were remembered and still practiced. The author tears that idea to shreds. This study begins with the earliest signs of Paleolithic human cultures in the British isles well over 10,000 years ago and continues through the Mesolithic and Neolithic into the Bronze Age and Iron Age. The Romans arrive with their religion. Rome falls, but the Roman religion remains, and the “Dark Ages” begin. The study continues all the way forward to what we would call modernity. Again and again, no matter what the era, the author finds that there is simply no way to reconstruct a picture of how pre-Christian peoples lived and how they saw the world. Instead, the available evidence is much like a Rorschach test: The existing evidence can be interpreted in many different ways, and no particular attempt at reconstruction can be proved, or disproved.

Still, is it useful to know as much as possible about what the archeology can tell us about pagan peoples? Absolutely, though we are left with little but our imaginations to try to make sense of it. The author actually is quite respectful of the use of imagination in interpreting the archeological evidence:

“Since the 1990s, it has been feasible to propose a mutual understanding between them [scholars and the imaginations of neo-Pagans], based on the more or less undoubted fact, strongly argued in the present book, that it is impossible to determine with any precision the nature of the religious beliefs and rites of the prehistoric British. It may fairly be argued, therefore, that present-day groups have a perfect right to re-create their own representations of those, and enact them as a personal religious practice — of the sort now generally given the name Pagan — provided that they remain within the rather broad limits of the material evidence (or, if they choose not to remain there, honestly to acknowledge the fact).”

Personally, I am not interested in religious practice. But I am very interested in the project of “re-enchantment.” There actually is a scholarship of re-enchantment. That scholarship starts with the sociology of disenchantment set out many decades ago by Max Weber, who borrowed the term disenchantment from the philosopher Friedrich Schiller. If you Google for it, you will find YouTube videos of re-enchantment scholars talking to each other at retreats. They’re smart, though to me they come across as gasbags who fell off the earth into an unhelpful New Agey sky of words, abstraction, and conferences. Re-enchantment, it seems to me, is a project that is not so much about words. Rather, re-enchantment wants fresh air, rock, ruins, green things, running water, and a bit of starlight.

Writing about Patrick, who helped to drive the enchantment (if not the snakes) out of Ireland, Hutton writes: “Indeed, he explicitly considered paganism to be dead in his society, its memorials consisting only of the icons of Romano-British deities, still visible within and without the ruined cities. He recalled that his compatriots had once worshipped divine powers inherent in the natural world, but stated proudly that in his time they regarded that world merely as created for the use of humans.” Regular readers of this blog know that, to me, Patrick is one of the worst villains in history, and that I see Patrick’s Augustinian theology as one of the worst inventions, ever, of the human mind.

This book was my reading material for a recent hiking trip in Scotland (photos here). I carried the book on my back for many a mile, and it has taken me almost three weeks since coming home to finish it. The book has been invaluable for giving me a greater appreciation of the mysterious oldness that is so apparent in Scottish landscapes.

But I’m an American, so what about America? Will it ever be possible to enchant, or re-enchant, the American landscape? As I see it, recovering, through re-enchantment, what was destroyed by the Roman religion — a tragedy that played out largely in Gaul and the British Isles — is essential to saving the earth. There are those who blame the Enlightenment — reason and science — for our predicament. But I don’t see it that way at all. The Enlightenment leaves us open to redemption by progress in philosophy, whereas the Roman religion poisoned the world with an ossified theology.

Hutton writes:

“The appearance of the faith of Christ required and produced just such a seismic change, by breaking most of the conventions of religious culture as they had existed in Europe and the Mediterranean basin since history began. It claimed the existence of a single, all-powerful, all-knowing, universally present and totally good deity, who had created the world and directed its fate. It also preached the existence of a force of cosmic evil in the universe, inferior by far to the single god but powerful in worldly affairs and set on subverting the divine plan for the universe. All creation was therefore polarized between those two forces, and human beings were offered the stark choice of salvation, by embracing the worship of the true deity and obeying his rules and commands, or damnation, by ignoring or opposing them and choosing other religious loyalties. The divine beings of other religions were regarded as nonexistent, having the status of lies, deceptions or allegories, or of personifications and servants of the forces of evil: effectively, as demons. The divine will was expressed through sacred writings, which true believers had to understand and expound correctly, creating the new discipline of theology, which replaced philosophy as the main means of understanding the universe and the human place in it.”

We seem to be stranded in a damaged and disenchanted world, but I’d rather not end on a pessimistic note. So I’ll try to hang on to my memories of what persists, in spite of modernity, in parts of the British isles and even in parts of America: fresh air, rock, ruins, green things, running water, and a bit of starlight.

Update: Here is a related review of another book, on how Christianity destroyed classical, as well as pagan, culture.