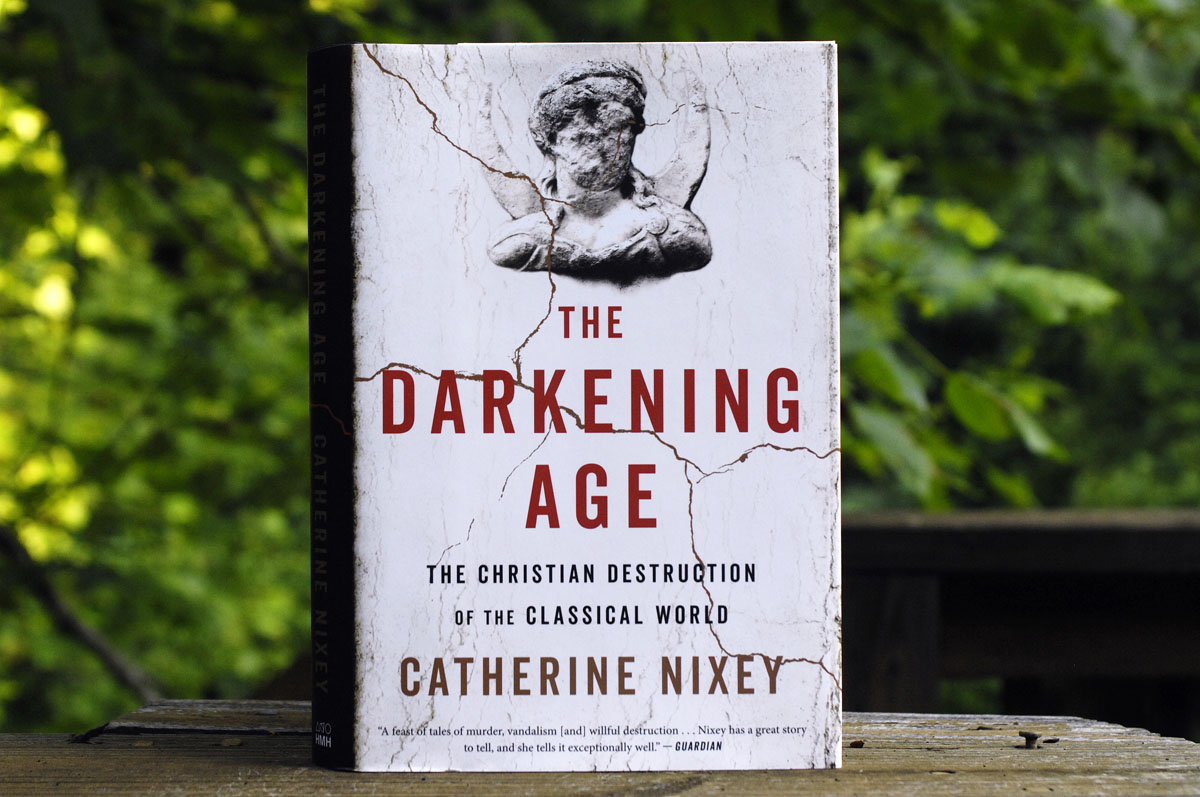

The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World. Catherine Nixey, Houghton Miflin Harcourt, 316 pages.

It is remarkably difficult, even with rational and educated contemporary minds, to challenge the belief that the church and the Christian religion have been a force of steady moral progress in the world. Yet that belief is easy to challenge. The opposing claim — that the church is, and always has been, an impediment to moral progress, a destroyer of superior systems, and all too often an engine of evil — is far from impossible to defend.

Early on in this book, Nixey writes, “Little of what is covered in this book is well known outside academic circles.” That is certainly true. The power and monopoly of the church flooded the world with church propaganda and suppressed the voices of any who dared to dissent. The church, and church people, wrote history. Yes, there have been movements such as the Enlightenment that have brought great moral and intellectual progress. But, where the church exists, there will be (and always has been) active resistance. American fundamentalism’s project of rolling back the Enlightenment (we now use the whitewashed term “evangelicalism”) shows clearly how the church operates to impede moral progress, to embed itself with the worst kind of political authority, and to maintain the power of the church.

It is inevitable that a book like this would attract criticism. Some critics have said that the book is one-sided. It’s not. Some have said that it’s a polemic. It’s not. Sneakier and more sophisticated critics have attacked the book for not being an academic book, as though that somehow discredits the book’s sources. But with 21 pages of notes, it’s easy enough to check Nixey’s sources. As I mentioned above, academics already know. What was lacking was a popular history to bring this historical material to the many who don’t yet know. Based on the Amazon rankings, the book is selling quite well.

Just what does the church have to offer to justify its existence, other than “salvation,” the bestselling product of charlatans (and not just Christian charlatans) for centuries?

It’s important to keep in mind that the New Testament contains no moral teachings that were truly new. All of the New Testament’s moral teachings are easily traced to earlier cults or philosophies, as I learned 50 years ago in Religion 101 and Religion 102. (That was a required course then at High Point College, now High Point University. I have written about my religion professor here.) The church’s early writings merely borrowed from other cults such as the Gnostics, or from pagan philosophy. Nor were those teachings state of the art, even then. The pagan philosophers of Athens and Antioch and Alexandria, and the intellectuals of Rome, correctly saw the Christian cult as embarrassingly hickish and backward. The church’s early texts were sorry work, poorly written by uneducated men. One of the services provided by Augustine of Hippo (354-430 A.D.), and one of the things that established Augustine as such an important figure in the early church, was that Augustine was among the first to bring a state-of-the-art education to the writing of Christian texts. That, given that Augustine was one of the foremost whack jobs in history, only made things worse.

In one important sense, though, the Christian religion and the church did innovate. Judaism was monotheistic, but Judaism did not proselytize. But not only did Christians proselytize, they also set out to destroy the competition. In the classical world, there was room for many gods and many philosophies. Philosophical inquiry was ongoing and ever-evolving. But the church insisted that there was one god and one true religion. Its truths were fixed, permanent, ossified, and unchallengeable. Everything else had to be eliminated. Even worse, anything was permissible to accomplish the elimination. That meant burning books, destroying pagan temples, and building a highly evolved system of persecution. To torture or burn a heretic’s body to save his soul was thought to be a Christian kindness. To burn books, to tear down temples, to destroy art, to force people to convert to Christianity (or else) was to serve God. This destruction and persecution is the subject of this book.

It is estimated that only 10 percent of classical literature survives. For Latin literature, the estimate is even worse — only 1 percent survives. Much of this was systematic destruction. Some of it was neglect.

At this point, I’m going to digress from the subject of Catherine Nixey’s book and indulge, just for amusement, in some existential speculation.

The church has been such a regressive force for so many centuries that we are obliged to use our imaginations to understand the scope of what the church has done. Just for the fun of it, here are two directions in which I let my own imagination run.

First:

The cosmos is an awfully big place. An article in Scientific American writes:

“If life can only arise under a narrow set of initial conditions, Forgan estimates there should be 361 advanced, stable civilizations in the Milky Way. If life can spread from one planet to another through biological molecules embedded in asteroids, though, the number jumps to nearly 38,000.”

Keep in mind that our own Milky Way galaxy is only one of something like 100 billion galaxies in the universe. In that context, what can we earthlings say about “God”? Some existential and intellectual modesty are called for here. And yet the Christian religion has taught every little mediocre-minded fundamentalist preacher in the American South to believe that he is qualified to instruct us on the mind of God. I can only laugh, though it isn’t funny.

Second:

What might the world be like if Christianity had never existed? We can never know, of course. But Christianity’s systematic destruction of the classical world, as well as its systematic destruction of the provincial cultures of western Europe (for example, the Celts), clearly imply that those cultures would have continued to exist and would have continued to evolve. Western civilization today would be much more classical and Celtic. Philosophy — and therefore moral progress — would have evolved much faster. It is impossible to imagine what our artists would have accomplished, in a world of philosophy and moral progress rather than dogma. Peace would have been easier to negotiate where plurality and reason are valued, so I think there would have been less war. Science would have advanced much more quickly. Yes, the ancients had slaves. So did we, until 150 years go. But without the church and its regressive influence, the arc of justice would have bent much more readily. Nature, earthly happiness, and life in general, would be honored rather than devalued and “fallen.” I doubt that the continued existence of our planet and species would be threatened as it is today.

I don’t propose book-burnings and persecution, though frankly that is just the kind of payback that the church has earned and deserves. But I do believe that civilized people have a moral, philosophical, and even religious duty to imagine the church and its products out of existence, to render the church forgotten. I believe that the Christian era was the worst wrong turn that history has ever taken. As rational, breathing, connected, upward-striving living creatures in a very large cosmos, we pay the price every day. “Where there is terror,” wrote Augustine, “there is salvation.” It’s hard to imagine a theology more depraved than that, and more deserving of oblivion.

Does she mention the influence of Zoroastrianism on Christianity David ? To my mind this is the most rational of the monotheistic faiths, a simple and flexible philosophy which we would have been better off with. I guess India and China provide us with speculative models as to what might have been. In India, and astoundingly rich philosophical tradition which was fairly pluralistic, allbiet operating alongside an intensely restrictive social system. Or China, which as I understand are the opposite of Indias intense religiousity. Chinese folk religion being a loose blend of Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhist. It’s seems as though the west is heading that way too, looking at the huge numbers of self identified ‘spritual but not religious ‘ and the huge influence of dharmic religion on the west since 1945.

Hi Chenda… The book mentions Zoroaster only in the context of intellectual work done in Alexandria between the time of Ptolemy II and Hypatia.

Nixey writes:

“According to one story, Ptolemy II, the ruler of Alexandria, had written a letter to every king and ruler on earth begging them to send his library works by all kinds of authors…. Not just in Greek, either, but in every language. Men, too, were sought and experts enlisted from every nation to act as translators [into Greek]…. Vast efforts were made with religious texts: two million lines of verse, said to be by the ancient Iranian prophet Zoroaster, were translated.”

I think it would be safe to assume that the Greek-speaking pagans of the classical era greatly valued the Zoroastrian texts and that the texts in the library of Alexandria did not survive the library’s destruction. But I know nothing about Zoroastrianism and its history, so I don’t really know anything about the history of the Zoroastrian texts. It’s possible that two million lines of authentic verse by Zoroaster did not really exist at that time — notice the hedge “said to be.”

Nixey references Gibbon for this, Vol. IV, Chapter 40, 265. I don’t want to give the impression that this book is based on Gibbon, though. Very few notes reference Gibbon.

Thanks David, it sounds like an interesting read. There has been a lot of debate about when Zoroaster lived, with dates between 500 BCE to 1200 BCE, although more recent scholarship has favoured the earlier dates. Essentially he promulgates the idea that good and evil are locked in a continuous battle, which takes place in the human mind as much as the material world. Ultimately, with human effort, good will triumph over evil. Human souls will reside in either heaven or a temporary hell depending on their actions in this world. Obviously this sounds similar to Christianity, and was likely very influential on it, but differs in important respects. Zoroaster doesn’t proscribe any stricts rules for his followers – he merely advises ‘good thoughts, good words and goods deeds.’ We have to determine ethics ourselves, and accept responsibility for our actions. There is no forgiveness for sins – our afterlife is merely a direct consequence of our lives. The Gathas, the 17 short hymms believed to be composed by Zoroaster, outline the entire philosophy. The KD Irani translation is worth a look – a short pamphlet which says so much more than the endless biblical trirades.

Well, it takes COURAGE publicly going against established religions (remember Salman Rushdie)- especially in the U.S.A. where churches seem to play an important role also in the social life 🙂

The Wheel of Life tells us that there’re times, where things are on their way up – but also long times where they’re in decline.

We’re in the latter, which everybody having reach a mature age can verify to – simply by thinking back 🙂

Eventually it’ll start building up again cause ‘everything, which has a beginning also has an end’ !!