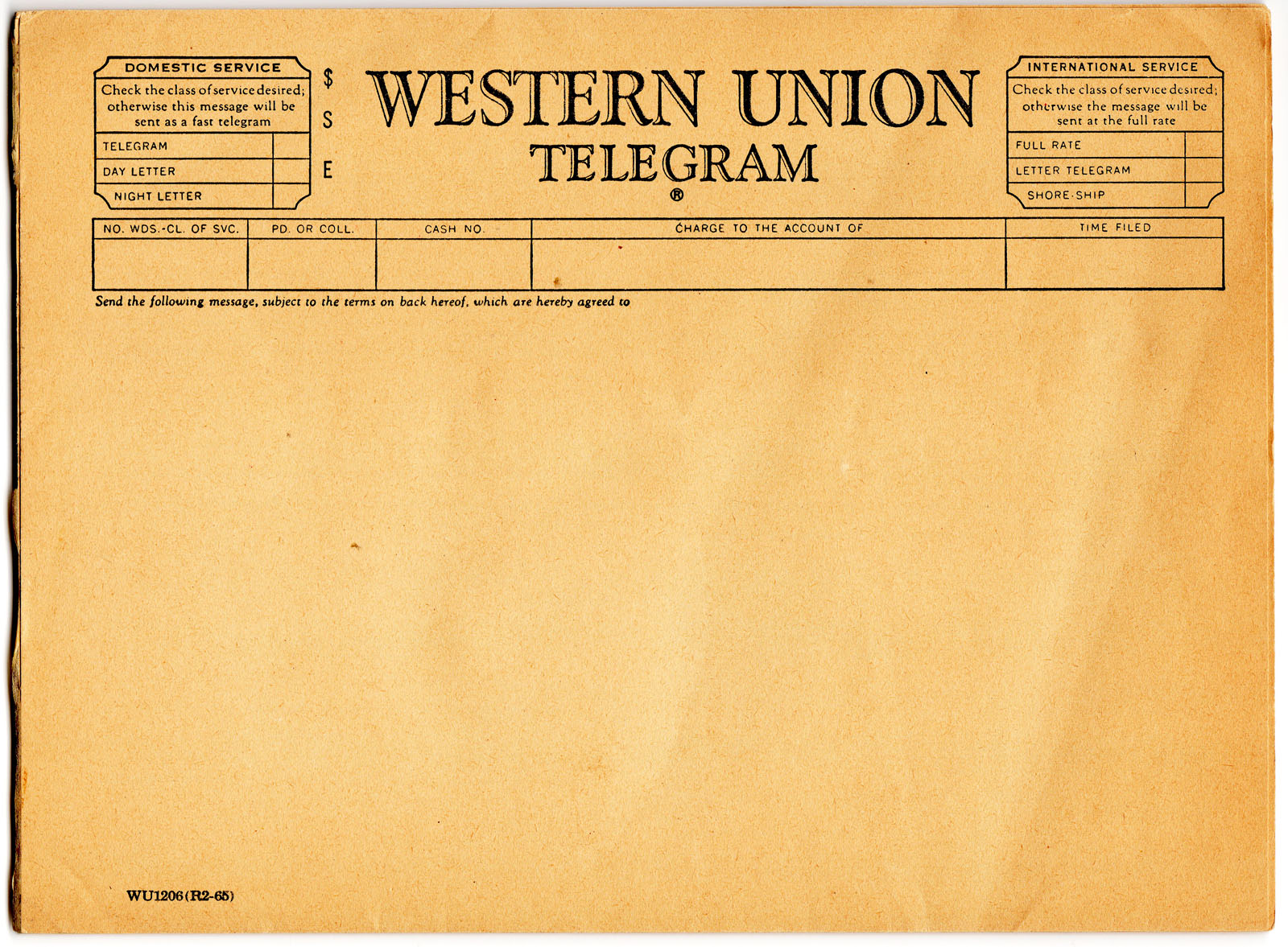

When I was a newspaper copy boy back in 1966, I operated a Teletype Model 19 exactly like this one. Teletypes like this used long-distance telephone lines. If you remember how much long-distance telephone calls used to cost, then you can imagine how expensive it was to keep a long-distance telephone line connected 24 hours a day from, say, New York to San Francisco. For decades, it was the Teletype network that brought us the news and supported commerce.

In September 1995, the Economist, which often gets things wrong because of its neoliberal obsessions, got something exactly right. The cover story was: “Suddenly Distance No Longer Matters.” Unfortunately I can’t find a link to this piece. But the point of it was that the era in which long distance communication was expensive was ending. Not only would the Internet make bandwidth very cheap, it would cost no more to communicate with the other side of the Pacific than with the other side of town.

And here we are today in a world in which distance doesn’t matter. Even ten years ago, we dreamed of an Internet with enough bandwidth to allow everyone everywhere to stream the movie of their choice. Today we’re almost there. It’s only those of us who live in rural areas who don’t have enough bandwidth for streaming high-definition movies.

But from the Internet’s beginnings in the 1990s, those with ugly agendas have been developing ways to take advantage of us. They give us free stuff, such as free email, but we don’t stop to think how they are making money off of us. Taking advantage of our innocence was immensely profitable, and many new billionaires were created. Harvesting information about how we spend our money in order to target ads seems relatively benign. But it’s worse than that. As Zeynap Tufekci writes today in the New York Times, “The need to keep users on the site for advertisers has led to design and algorithm choices that increase engagement, often with false, inflammatory or tribalizing content that research shows travels much more easily on social media.”

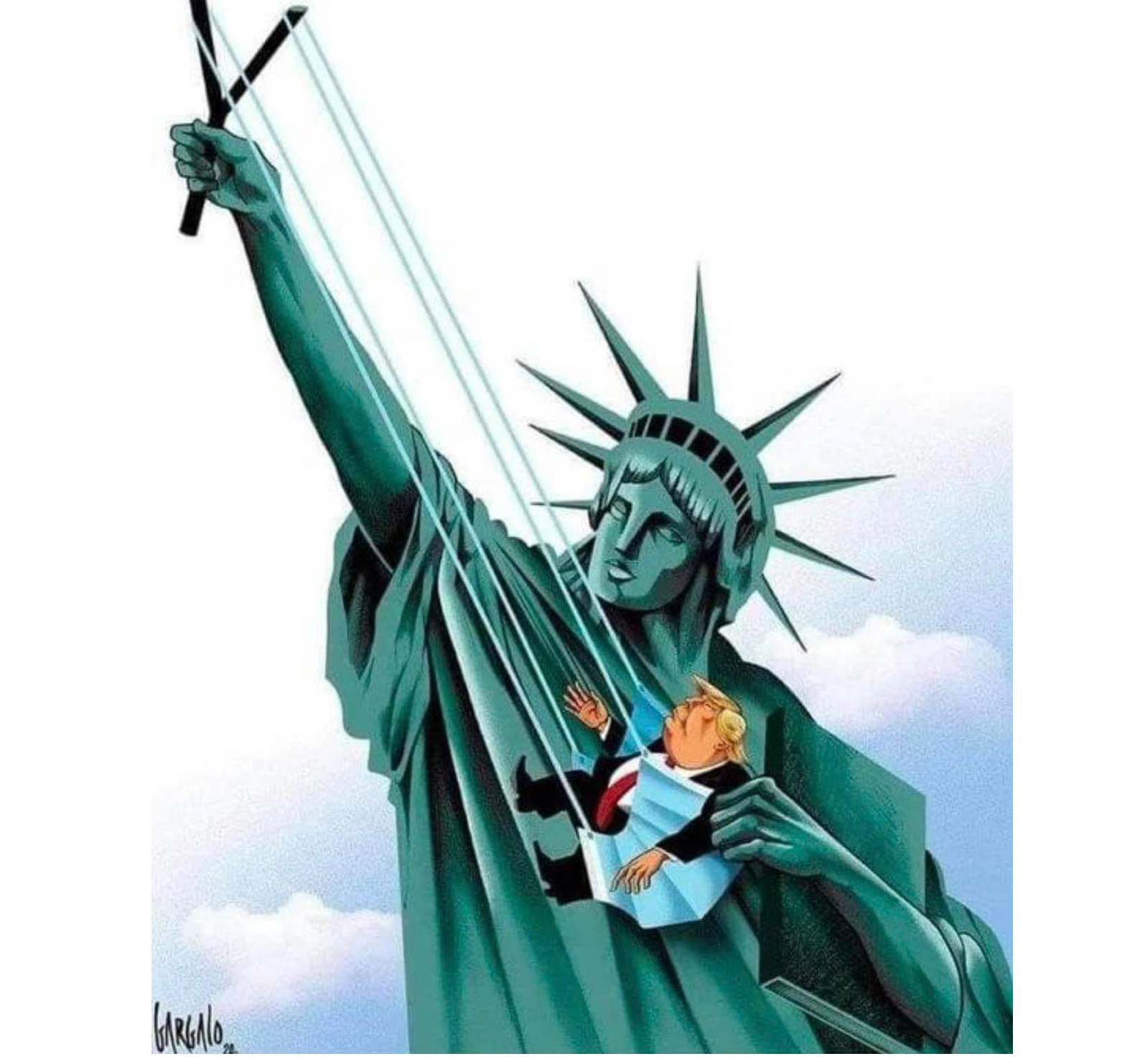

It’s entirely reasonable, in 2022, to ask the question: If it weren’t for the ways in which cheap bandwidth has been used to monitor us and manipulate us, would democracies today be at risk of takeover by the authoritarian oligarchy? Could Trump have happened?

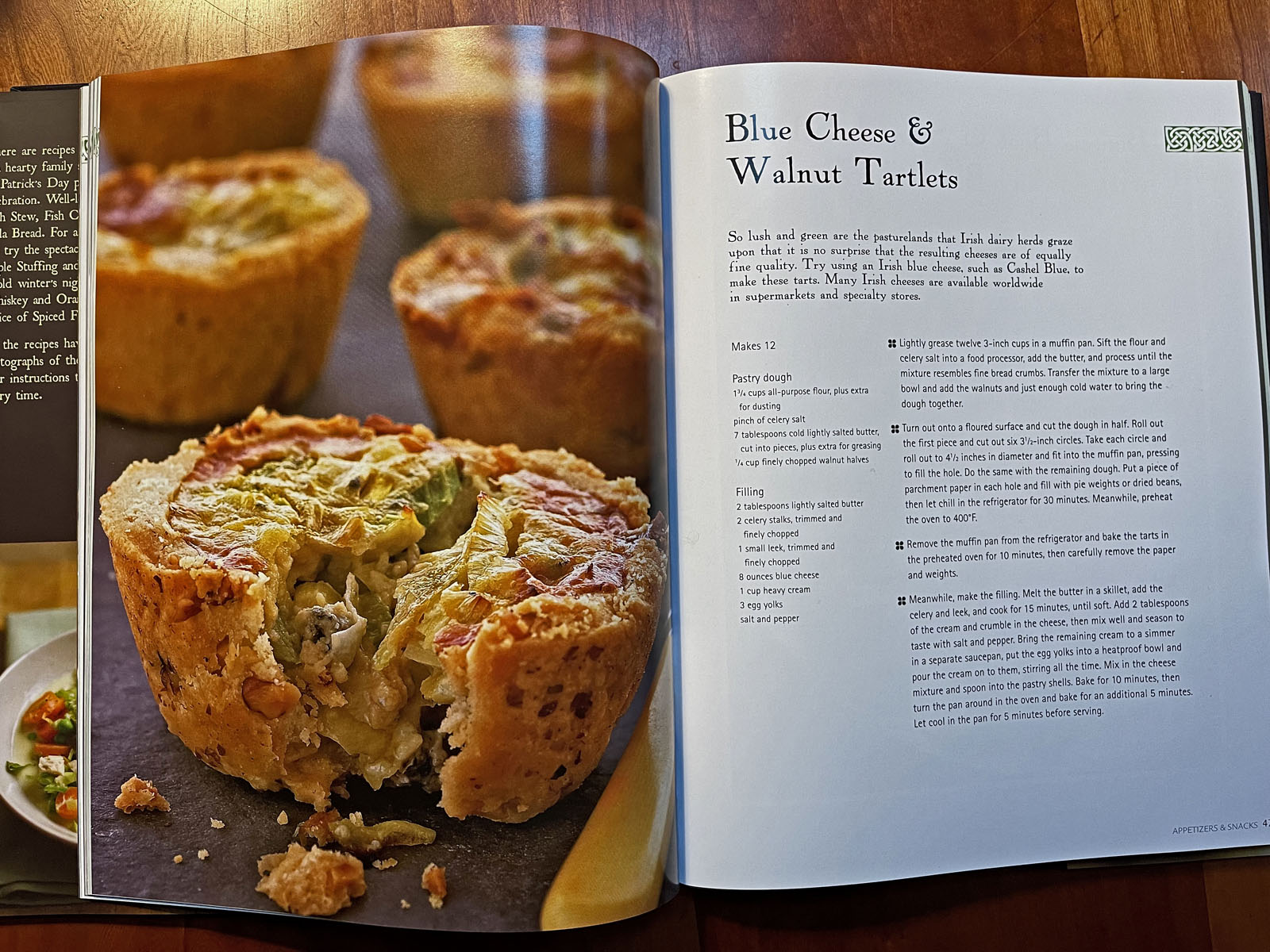

There are three excellent pieces in the New York Times today about how tech is being used against us:

Tufekci’s piece is: “We Pay an Ugly Cost for Ads on Twitter.”

Brian X. Chen, the lead consumer technology writer for the New York Times, has this piece: “Personal Tech Has Changed. So Must Our Coverage of It: Our tech problems have become more complex, so we are rebooting the Tech Fix column to focus on the societal implications of the tech we use.”

Farhad Monjoo has a bleak progress report on Mark Zuckerburg’s plan to entrap us in his “metaverse,” in order to own us and advertise us to death: “My Sad, Lonely, Expensive Adventures in Zuckerberg’s V.R.”

I have used “gift” links for the articles above, so you should be able to read the articles without a subscription to the New York Times.

Sometimes I think that we’d all be better off if we could go back to the world of Teletypes and expensive long-distance telephone calls. As Tufekci mentions in the article above, and as I well know from a career in newspapers, publishers once went to great lengths to keep the advertising department out of the newsroom. Those days are over. I was there back in 2000 for the horrible merger of the staffs of the San Francisco Examiner and the San Francisco Chronicle. It was already understood then that newspapers’ continued existence was endangered, because craigslist had destroyed newspapers’ market for classified advertising. Publishers’ solution was to unleash hordes of “bean counters,” as we called them, on newsrooms to teach journalists that they had to help find ways to “monetize” the news. One of the reasons the New York Times has survived, as Tufekci points out, is that the Times found a way to rely on subscriptions rather than advertising.

I despair of any means ever being found to keep the vast majority of us from being exploited and manipulated by today’s tech giants and how they use costless bandwidth. Some people make fun of me, as though I’m paranoid, for using a VPN, for refusing to use free email, for never having used Twitter, and for taking steps to make sure that Mark Zuckerberg knows as little about me as possible. For years I’ve had the ability to encrypt and sign my emails using a private key, but no one else I know bothers to do that, so encryption isn’t an option for me. We could put an end to spam, to email scams, and to email phishing tomorrow if everyone signed their email with a private encryption key. But that’s the last thing that Internet giants want. Google makes millions by analyzing people’s emails and by tracking who communicates with whom. There is no perfect defense, though, other than going off the grid.

The most dangerous threat, though, from cheap bandwidth is the ability to push out lies and to mass-manipulate people who don’t know any better. There is nothing that we can do for that kind of people. Time and again, I’ve heard people refer to eagerly ingesting conspiracy theories as “doing their own research.” We’re on our own, hanging by the thin thread of hope that enough of us will remain sane to steer clear of the authoritarian dystopia that is being planned for us.