“I do not pretend to understand the moral universe; the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways; I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends toward justice.”

–Theodore Parker, 1810-1860

We could say that we believe in the arc of justice, but that would be a useless statement, because our beliefs, whatever they may be, have no effect on the reality outside our own minds. Even if our beliefs guide our actions in the real world, the effect is weak and indirect. As much as we might like to, we can’t change the world simply by wishing and by thinking. Beliefs may indirectly lead to change, especially when lots of people hold similar beliefs and act in accord with them. But beliefs alone don’t change anything. I’ve had a saying about this for many years: You can believe until you’re blue in the face, but that doesn’t change anything.

But we can make an if-then proposition that I think is sound and reasonable. It’s this: If there is such a thing as the arc of justice, then to stand in its way, inevitably, sooner or later, is to be found wrong. Not only does that mean that one’s thinking was wrong. It also means that, at some point in the future, one will enter into a state of shame for having stood in the way of the arc of justice.

We could cite many examples of this proposition, from Rome to the present. Religion’s track record is especially damning. For example, the largest Christian denomination in America, the Southern Baptist Convention, militantly supported slavery during the 19th Century. During the 20th Century, it supported racial segregation. In 1995, though it took 150 years, it apologized for its history. Even after the apology, some of the meanest people in the country remain in control of the Southern Baptist Convention and still stand in the way of the arc of justice. But at least, as the arc of justice moved on, church people had to admit that they were wrong. It’s because of the arc of justice that we don’t burn people at the stake anymore, or put people like Oscar Wilde in prison, or hang people for stealing a crust of bread, or beat our children.

Over the centuries, moral error after moral error by the church, in spite of its claim to speak for God, shows that the arc of justice — and this should be no surprise — is and always has been more powerful than religion. Not only that, looking toward the future, religion weakens as the arc bends toward justice. The arc bends. To the degree that it is ossified and refuses to bend, religion inevitably breaks. Church people see the decline in church membership as a moral emergency. I see it as moral progress.

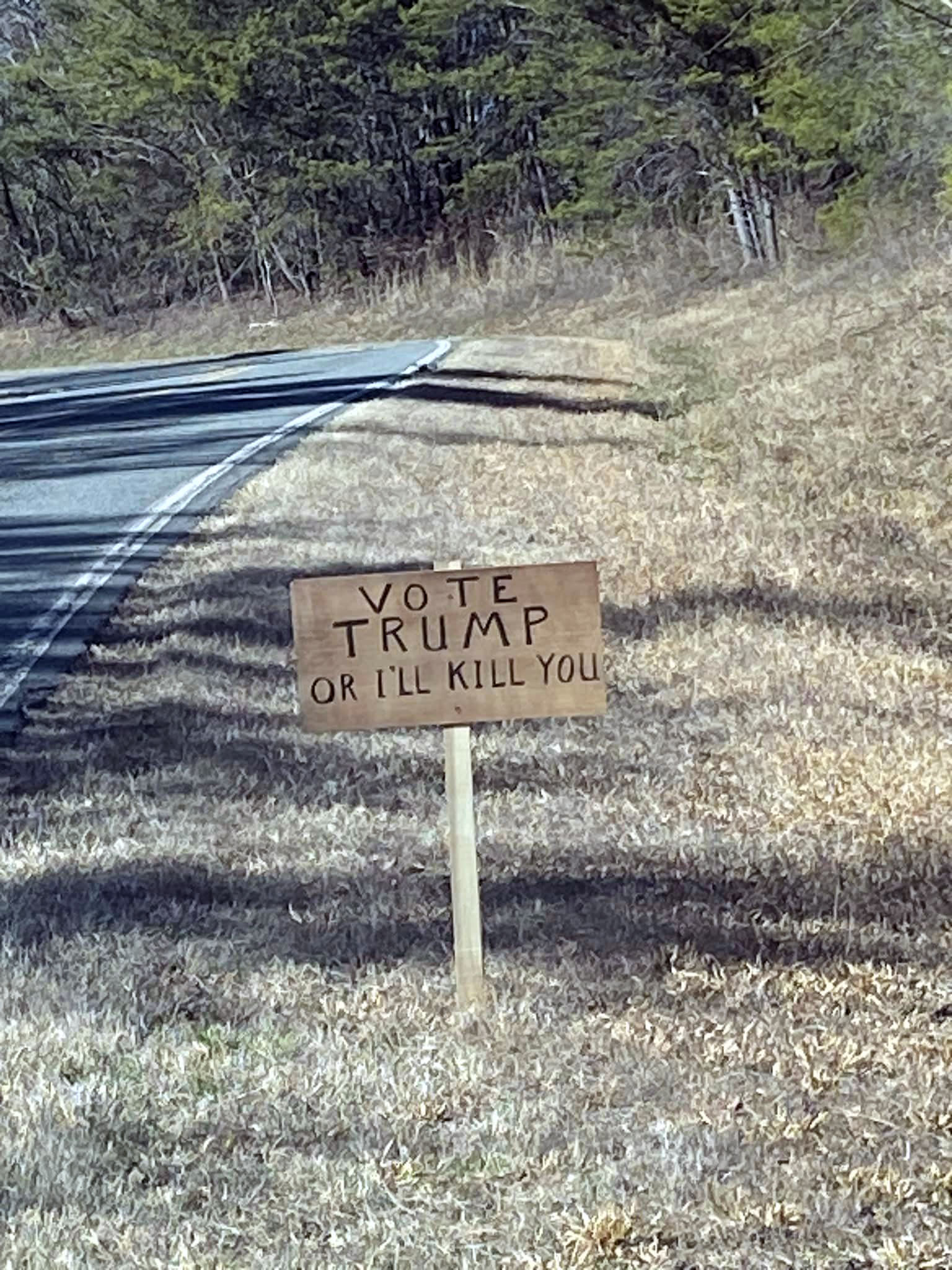

As liberals, this is where our confidence can come from, as well as our optimism. It can be the basis of a politics. It’s why I say that the entire spectrum of conservatism, from dishonest both-sides centrism to the neo-Nazis, is wrong, wrong-headed, and causes harm. And for many people, merely to stand in the way of the arc of justice is not enough. They work to reverse moral progress and roll back the clock.

Theodore Parker, a theologian, is sometimes referred to as a heretic. He saw long ago that the church is not an instrument of moral progress. Rather, far more often, it has been the opposite. I can’t take seriously the claim that religion has ever been on the leading edge of the arc of justice. Classical philosophy, if the church had allowed it to evolve rather than repressing it, would have brought far more light to the Dark Ages than the church ever did. The Enlightenment might have come sooner, had there not been so much resistance. It is ideas, and an expanding concept of justice and fairness, that lead the arc of justice toward greater justice.

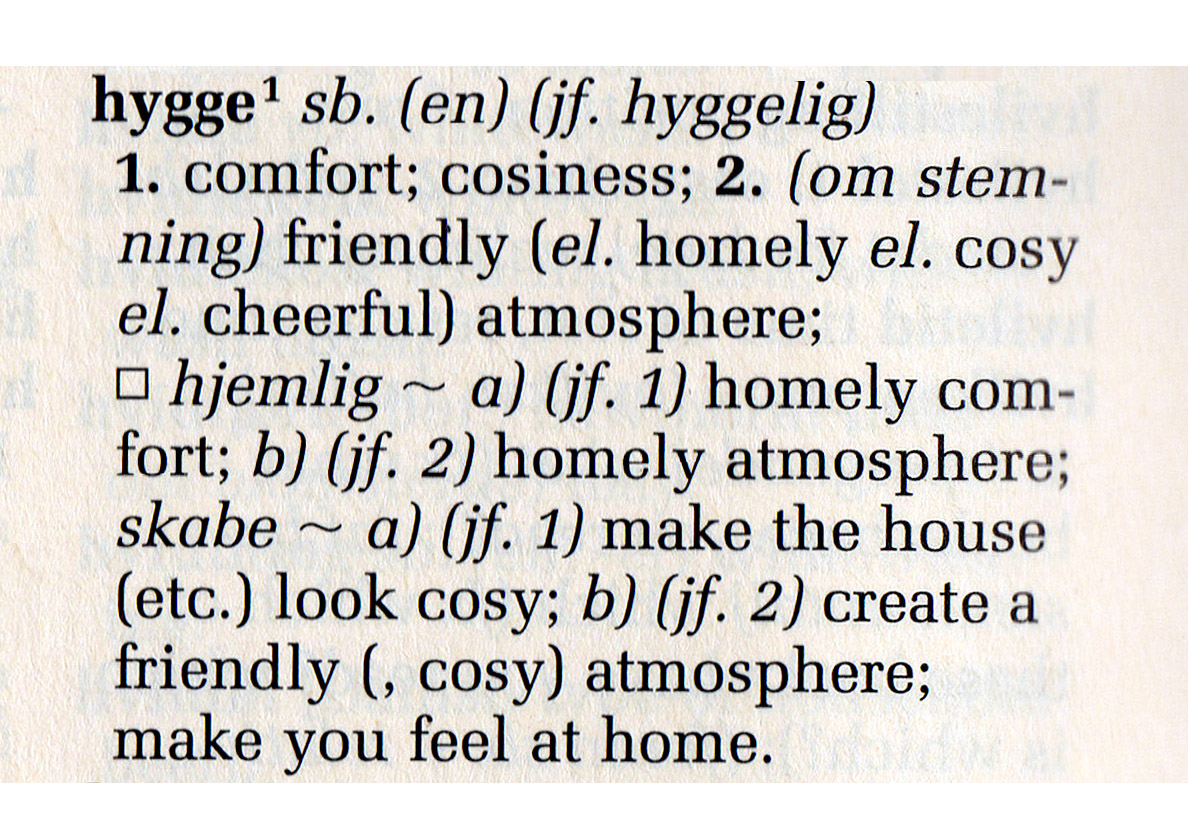

The Enlightenment, of course, brought a revolution in moral philosophy. Still, for a hundred to two hundred years, utilitarianism was the state of the art in ethics — the idea of the greatest good for the greatest number. There are still utilitarians, but ideas about justice and fairness have expanded. I am among those who see utilitarianism as obsolete after John Rawls’ justice as fairness (1971). The course of the arc of justice in our time, I believe, is best described by John Rawls’ justice as fairness. As Theodore Parker says, our sight, in any era, may reach but little ways. But from what we can see now, the arc of justice is bending in the direction described by John Rawls.

Rawls’ philosophy may be complex and a challenge to read, but its key idea boils down to something simple, and, to most minds, obvious: We cannot justify being unfair to anyone (usually the poor, the stigmatized, and the weak), even if others want to gain (usually wealth and privilege and power) from that unfairness. This idea is steadily being integrated into liberal politics. Meanwhile, the interest of conservative politics in wealth, privilege, and domination increasingly finds so much fairness threatening. Most people have never heard of John Rawls. Still, as though by magic, Rawls’ philosophy is in the Zeitgeist. Conservatives feel it as clearly as liberals feel it, which is why they are in such a panic to resist it. It puts wealth, privilege, and power in a different light, light that is not to conservative liking.

Thomas Piketty caused quite a stir in 2013 with Capital in the Twenty-First Century. His second book, A Brief History of Equality, got less attention. But in this second book Piketty argued that there has been a steady improvement in equality since 1780, and he explains why he is optimistic about future progress. Given that millions have died since 1780 in the struggle against domination, Piketty’s optimism may seem misplaced. But I think he is right, because even when those who crave domination win, they don’t — can’t — win for long. Just ask the enslavers of the 19th Century, or the Nazis of the 20th, or the racists of the Civil Rights era. In a decade or two, ask Putin. Ask Trump, once the courts are done with him.

We have just been through one of those times, when those who work together to block and reverse the arc of justice get the upper hand. This is what happened when, in 2016, Donald Trump was installed in the White House by wealthy elites whose domination is threatened by fairness, aided by “populist” subjects who were all too easy to deceive.

Now the arc of justice is catching up with them. For some, prison. For others, only shame. Still, some of them are so hardened that will never feel any shame for the ugliness of their actions and their ideas. But the children of the future, from what we already can see now from the direction in which the arc of justice bends, will see things differently.