The Tristan Chord: Wagner and Philosophy. By Bryan McGee, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 2000.

When I bought this book, I expected only to browse it. I ended up devouring it. As I’ve mentioned in other posts, you never know where research for a novel might lead you. In this case, I was thinking about musical metaphors and interesting ideas for the Socratic dialogues in Oratorio in Ursa Major.

Truth be known, I am not that great a fan of Richard Wagner. I even have been to a performance of “Tristan and Isolde” by the San Francisco Opera, and that did not win me over to the music. I find the music (four hours of it!) difficult to listen to. Still, the legend of Tristan and Isolde is archetypal in Western culture. Jake, my protagonist and hero in Fugue and Oratorio in Ursa Major, often makes drawings of unusual buildings, and he has a bit of a thing for towers covered with vines and thorns (like the tombs of Tristan and Isolde in some tellings of the story).

Nevertheless, I think it’s very important to know just what a landmark Wagner’s “Tristan and Isolde” was in the 19th Century. The music was like nothing ever heard before. Orchestras declared it impossible to play. Singers said that it was impossible to sing. There were more than 70 rehearsals of the opera in Vienna between 1862 and 1864, but the performance was called off and the opera was declared unperformable. Finally Wagner succeeded in staging it, in 1865 — 150 years ago.

After 150 years, the debate still runs hot in some musical circles. Just what is Wagner’s Tristan chord? Is it just a modified minor seventh chord? Or is that G-sharp an appoggiatura to the A, putting the chord in a whole different light? (It’s not necessary to understand the music theory here. The point is that the experts have been arguing and disagreeing for 150 years, and there are several theories about what the chord is.)

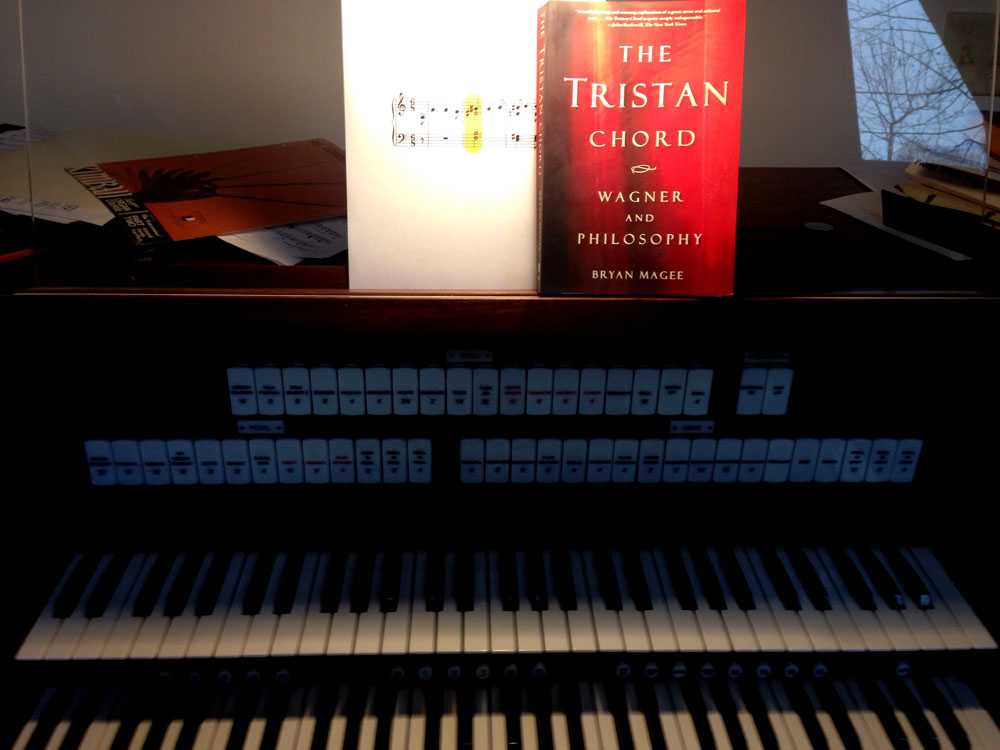

Here is what the music looks like:

Here it is played on the Acorn Abbey organ:

Stephen Fry did an excellent documentary on the Tristan chord called “Wagner and Me” back in 2010. (More about this Fry documentary in a moment.) Fry emphasizes the unbearable longing that the chord expresses. Our ears want the chord to resolve, but in four hours of music, it never does — not until the very end of the opera. No wonder some people consider the opera to be torture.

What do we mean by a chord resolving? Even if you can’t read music and don’t know a thing about music theory, your ear knows all the rules. For example, if I sing the first line of this ditty:

Old MacDonald had a farm!

Your ear will give you no rest until you hear that musical phrase resolved:

Eee-aye eee-aye oh!

There. That resolved it. Or think of the last note of pretty much any song:

And crown thy good

With brotherhood

From sea to shining —

Your ear will give you no rest until you hear the last note, in which the dominant chord, as it always must, resolves to the tonic:

Sea!

Believe me, even if you think you know nothing about music, if you love music and listen to music, your ear knows all the rules. I doubt that any metaphysical system will ever be able to explain why music has the emotional effect on us that it has, but part of that musical effect, surely, is creating tension — even longing — in unresolved harmonies and melodies, and then taking us along for a nice ride toward the resolution.

In many ways, John Williams (who wrote the music for “Star Wars”) is the Wagner of our time. Listen to this performance of Leia’s theme and think about how the music creates longing and tension and demands that we listen until we hear these tensions resolved. The final resolution comes quietly at 4:11, with a lonely note from the violin, followed by the remainder of the tonic chord in an arpeggio from the harp. Again, it doesn’t matter what the “tonic” chord is or what an “arpeggio” on the harp is. Your ear knows when it has finally got what it wanted. When the final chord finally comes, the orchestra quietly takes over the chord from the violin and the harp and holds the chord for many beats, to let the resolution sink in and to give our ear the peace it was longing for:

You’re not in a hurry, are you?

Here’s an excerpt from Stephen Fry’s “Wagner and Me” documentary:

Part of what makes Bryan Magee’s book so fascinating is his discussion of the philosophy of Immanuel Kant and Arthur Schopenhauer, both of whom greatly influenced Wagner. Over the years, I have made repeated attempts to read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, and each time I have been turned back by the impenetrable density of Kant’s writing. Magee acknowledges that Kant’s writing was unnecessarily turgid and boils Kant down. We are all Kantists now. Magee does the same thing for Schopenhauer. And thus I learned that I am pretty much a Schopenhauerian, though not quite as pessimistic.

Magee is an engaging writer and has written a number of books aimed at making modern philosophy comprehensible to ordinary people.

Hello! I really enjoyed this post. You talk about music with much more clarity than any music theory teacher I have ever met.

I did a semester long course on Kant while in college, and was never able to get through ‘Critique of Pure Reason’ either. I will have to pick up this book, and learn what I never did in school.

It’s always a treat to see your new posts. You obviously have an immense amount of knowledge, and you share it with the world in a great way.

Thank you for your nice words, Andrew. In my novels, I want to include an emotional experience for readers. That’s a challenge when you’re working with only words on paper. It’s part poetry, I think, and part foreshadowings and unresolved tensions that are set up earlier in the novel and which are all brought together quickly and unexpectedly at the right moment. Still, there’s something to be learned from film and opera about how it can be done.

I’ve been at school all day, so of course I don’t have a brain cell left to leave an intelligent response to this smart post. You get to read interesting books. I read student papers. Sigh.

Anyway, you’re exactly right that people don’t need to understand all the lingo of musicology to get it. They don’t have to “know” about music to get it. Their brains get it because their brains spend a lifetime, even subconsciously, learning the language.

In music scholarship, it’s called “habituation.” For a book-length discussion, you could start with Peter Yates’ “Twentieth Century Music,” published in 1967 and revised a year later.

Here: http://www.amazon.com/Twentieth-Century-Music-Peter-Yates/dp/B0013PLBFY/ref=sr_1_11?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1448919328&sr=1-11&keywords=peter+yates

The publication date is significant because contemporary composers and music scholars at the time were thinking of “habituation” as a problem that needed to be overcome. They did not WANT your ear to dictate where the chord progression went and especially where it ended. They wanted to be completely free to tell the listener where the the music would go, whether the listener found it arbitrary and unsatisfying or not — thus alienating countless listeners.

Hard to believe now, but this was exactly the resistance Wagner encountered in his day. If it didn’t sound like Mozart or Haydn or Beethoven, it didn’t “sound like” music, at least not to the “habituated” ear. Hell, come to think of it, Beethoven faced a lot of the same resistance in his day. And so it goes.

For me, the problem with Wagner is the same as with Kant: “unnecessarily turgid,” as you say, particularly on the issue of unnecessary — and completely ego-driven — length. I simply do not need “Tristan und Isolde” to be four hours. Same with Kant, the man who 10 pages to say what could be said in two. Schopenhauer is definitely the way to go (and not overly pessimistic). Another solution is to read scholars who have done the hard slog through their original-language writings so you don’t have to!

As for the “Tristan chord,” it goes to what music scholars talk about as “tension and release,” which maps all music compositions. Martha Graham famously brought that idea into dance as a theoretical framework, which she famously (and smartly) wrote and lectured about. She said it had to do with the rhythms of sex, which was, of course, a little over the line for stodgy music scholars. Draw your own (sexual or asexual) conclusions.

As for the chord itself, you certainly could think of the G-sharp as a appaggiatura leading to the next chord, though that would make the next, resolved chord the real “Tristan chord.” It might be more interesting and productive to think of the “Tristan chord” in relation to or working in tandem with next-to-last chord of the sequence, like cousins with similar attributes and, obviously, similar resolutions.

Here’s an experiment: Sit at the organ and play the so-called “Tristan chord” and then play the next-to-last chord. Then alternate them over and over. Hell, see what happens when you play both chords at once.

I suppose that the point I’m trying to make, like Yates and contemporary composers trying to move from the Tonal Era to the Sound Era, is that the entire sequence you quoted above was unsettling for listeners at the time because Wagner was demanding that the ear accept not a simple sequence of “tension and release” but a more complex sequence of “tension, release, tension, release” and, further, that the listener must accept the entire package together as a whole — else it would not make sense.

Another way to say that is that there is not one “Tristan chord.” There are two, and they can’t be separated. Or, if you like, you look at the entire sequence together as the so-called “Tristan chord” — as when an organist will add ornamentation between the chords of a simple sequence to add connective tissue and tonal interest.

To put it yet another way, the essential sequence itself is but two chords, the two *resolved* chords that follow the two so-called “Tristan chords” — and everything else is sauce.

See you.

DCS

And sorry for the typos. Feel free to fix them if you like.

DCS: Thank you for taking the time out of your busy day to write this excellent response.

It’s a very interesting point you make about “habituation” and how unlistenable 20th century composers alienated concertgoers. I think it’s fascinating that those composers didn’t just alienate listeners. They also alienated musicians, and orchestras. An old friend of mine who was in the San Francisco Symphony (and now the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra) used to complain that the orchestra hated playing the modern stuff. He would wear earplugs and just saw away as required by the score (he was a violist).

Anyway, Kant and Schopenhauer notwithstanding, the Platonist in me suspects that there is something Platonic beyond just habituation. I have a strong suspicion that music — and its hidden structure and logic — pre-exist in the Platonic world, just as do math, or geometry. The best defense of this idea, I think, is to be found in the books of the Platonist Roger Penrose, the physicist and mathematician whom I regard as our living Einstein.

I strongly suspect that the minds even of animals are in touch with the Platonic world of music — though it’s hard to deny that there also is an element of habituation. But I believe they do have the capacity to understand and love music. My dog used to come and lie down under the piano whenever I started playing. For a long time, Lily was terrified by the noise of the organ and would run and hide. Gradually, she learned to run and hide only if I played loud. But now, no matter how loud I play, she lies in the sphinx position behind the organ bench and watches and listens.