An article in a recent New Yorker magazine made me even more appreciative of the choral tradition of the Anglican church, not to mention more glad that I had the opportunity to sing in the choir at an Episcopalian Christmas service last month. The article is in the Jan. 10, 2011, issue: “Many Voices: Blue Heron brings a hint of the Baroque to Renaissance polyphony.” The article is available on the New Yorker web site, but a subscription is required.

The article is about some newer choral groups who have been exploring the same historical terrain as the Tallis Scholars, who have been around since the 1970s. The article contains this rather intriguing line: “Likewise, the austere allure of the Tallis Scholars is inseparable from the Anglican choral tradition, which owes much to Victorian values.” This reference to Victorian values is left unexplained, but I assume it means that, even though the roots of Anglican music lie deep in the past, in the Medieval monastic tradition and in the Golden Age that occurred during the reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, Anglican music nevertheless was affected by the theological — and musical — emphasis on the more personal forms of salvation that marked the 19th Century.

I was raised in the Southern Baptist Church, the music of which largely comes from this 19th Century tradition. My first organ teacher was a Moravian and organist at a small Moravian church. I sometimes substituted for her when she was on vacation. Though not as ancient as the Anglican musical tradition, Moravian music reaches back a century or two earlier than the Baptist tradition, to the time of J.S. Bach.

It is strange that, though I’ve been singing since I was a child, and though I used to accompany small congregations, I had never been in a choir until last month. I’m thinking that I’d like to do it again at Easter. The YouTube videos to which I’ve linked here capture some of the thrill of singing in a choir, especially the many YouTube videos of King’s College Cambridge. Practicing the organ was always such lonely work, usually done in dark, underheated churches. But practicing with a choir is a very different thing.

When rehearsals started in November for St. Paul’s Christmas program, I almost convinced myself that I’d never learn the bass parts for 45 or so pages of music. I wasn’t alone, though. Everyone in the choir, including the professional section leaders, had lots of work to do. But then something stunning happens at the final performance. Not only did the members of the choir know the music, they’d even memorized most of the words. At last they could take their eyes off the score and watch the director. And no longer is the director playing the role of the kindly tyrant. With the director’s back to the congregation (which was packed for the Christmas service), they can’t see that he is smiling at us, winking at us, gesticulating when his hands and arms are insufficient to communicate with us. Suddenly we are totally under his control, attentive and obedient. Every voice starts precisely on the beat. When he requests a crescendo or a ritardando, he gets it. We hold the last note, forte, nearly out of breath, the power of the organ supporting us, but not until the director makes a little chopping gesture with his hands do we stop, all precisely together. The sound reverberates through the church. I dare to shift my eyes off the director now and see that members of the congregation are smiling. We almost had them on the edge of their seats. Choral music does that to people. Sometimes, listening to an organ, especially an infectiously complex fugue by J.S. Bach, I find myself hyperventilating in sympathy with the organ and the huge amount of breath it is expending. Choral music, too, pulls us in somehow. It makes us want to sing with other people. When the choir comes up for air, so does the congregation.

Recently, after watching the movie Winter’s Bone, I was trying to explain to a friend the distinction between the music of the high church (the Anglicans) and the low church (pretty much everybody else). Despite the differences, these musical traditions have much in common, and both are wonderful. Part of the appeal of Winter’s Bone was the soundtrack, with a completely unexpected and beautiful performance of the very low church “Farther Along.” I sang along with it, in harmony. I’m linking to that as well.

Low church and high church — both are rich, beautiful, and deep. Even a pagan must pay his respects.

YouTube: The Tallis Scholars sing Thomas Tallis

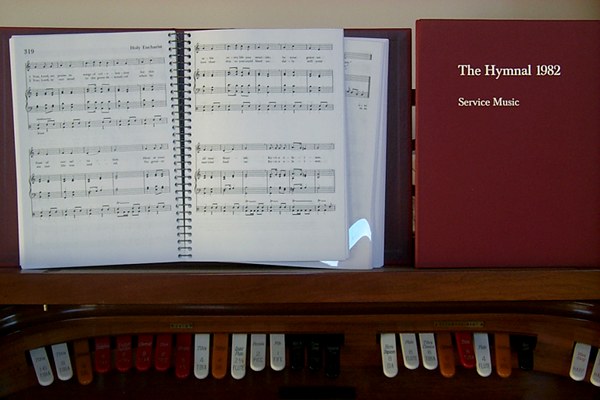

My new Episcopal hymnals, ordered from Amazon

YouTube: Farther Along, from the soundtrack of Winter’s Bone

What exactly is low & high church? Century’s/Years?

“High church” is to a large degree a theological proposition, emphasizing the history and authority of the Catholic church. The Anglican cathedrals of Britain, certainly, are high church. Personally I think “high church” implies some class distinction. High churches are usually wealthier, have grander buildings, highly professional music programs, etc. Protestant churches are not high church.

I also meant to say that “Farther Along” (follow the YouTube link) is an excellent example of the low church music typical of the Appalachian highlands. The other links are to high church music.

I’ve read several novels by Barbara Pym, a British novelist, and high vs low churches were mentioned. I think one favored incense, and depending on the character in the novel may have been spoken of distainfully. I always wondered what was meant by high vs low.