John Buchan (right) and Roy Tash looking through the viewfinder of an Akeley camera. Source: Library and Archive of Canada, c. 1937.

Discovering just one new extraordinarily good writer a year is a wonderful thing, though all my bookselves are full, and, once again, teetering stacks of unshelved books are forming on the table beside my bed. Last year that writer was C.J. Sansom and his series of seven Shardlake novels. This year it is John Buchan.

Though connoisseurs of spy novels always include Buchan on their lists, I am not a connoisseur of spy novels. (If I am a connoisseur of anything, it’s novels that are not set in the here and now.) It was ChatGPT that made me aware of Buchan after I asked for book recommendations. That particular ChatGPT discussion was about how writers who came out of Oxford tend to have a rare confidence with the English language. They’re elite and they know it, thus they have no need to show off or — heaven forbid — experiment with language. Thus they write in the plain, lucid, transparent Anglo-Saxon that is, in my opinion anyway, the best kind of language for storytelling in English.

Many of Buchan’s novels are more than a hundred years old. But the writing is entirely modern. This puzzled me until I realized that plain Anglo-Saxon English changes very little from century to century. Whereas florid writing styles that draw heavily on the Latin side of English go out of fashion quickly. This, I suspect, is the main reason why hardly anybody reads Sir Walter Scott anymore (more on Sir Walter Scott below). Scott loved the Scots language and records it faithfully. But ironically Scott’s English is so wordy, congestive, and archaic that it demands too much of today’s readers.

Buchan is best known for The Thirty-Nine Steps, which Alfred Hitchcock made into a movie in 1935. After I read The Thirty-Nine Steps, I rented the movie for $2.99 and couldn’t finish watching it. It was just too primitive. Plus Hitchcock fiddled with the story to dumb it down. Hitchcock wanted to make a movie of Greenmantle, but I read that Hitchcock and Buchan’s heirs couldn’t agree on a price for the rights.

But forget Hitchcock. Moviemaking technology in Hitchcock’s time was too primitive to match the vividness that comes through in Buchan’s storytelling. After Greenmantle, I will read Witch Wood, which some readers say is Buchan’s masterpiece.

Sir Walter Scott

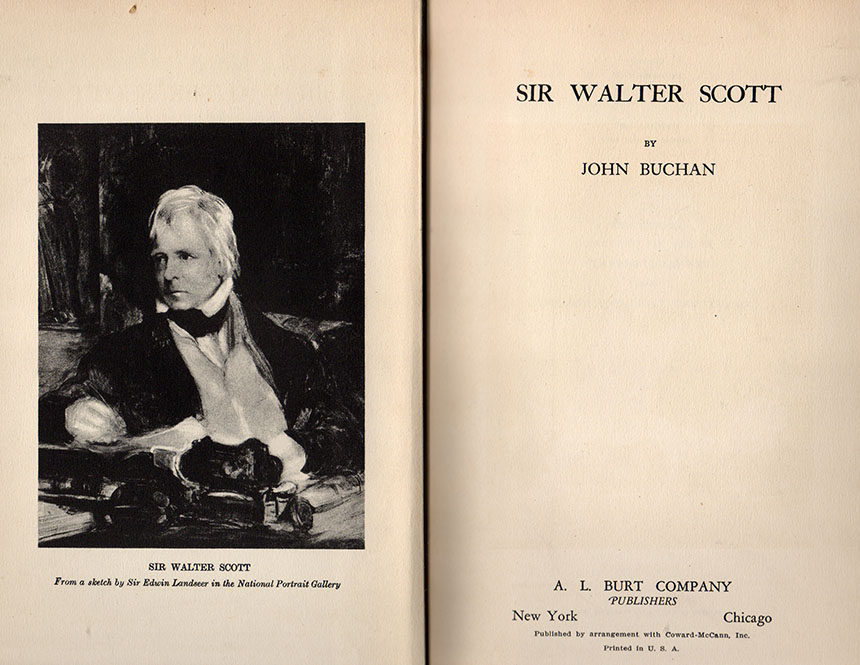

Buchan was a prolific writer, and not just of fiction. He wrote a biography of Sir Walter Scott that was published in 1932. On eBay I bought an American edition of that biography that also was published in 1932. It will be a nice reference book to have. The definitive biography of Sir Walter Scott, by John Gibson Lockhart, was published in seven volumes in 1837 and 1838. Those books would be almost impossible to find outside of university libraries, and as far as I know the Lockhart biography has never been digitized.

Buchan was born in Scotland. He was Governor General of Canada from 1935 until his death in 1940. On December 7, 1923, Buchan was the speaker at the annual dinner of the Edinburgh Sir Walter Scott Club. The text of his talk is available on line. Buchan and I seem to agree on something I have often said about Scott’s novels — that though Scott was fascinated with kings and queens and the famous figures of Scottish history, Scott is at his best when the story involves Scottish peasants. From Buchan’s talk:

My last example is Sir Walter’s treatment of his Scottish peasants. His kinship to the soil was so close that in their portraiture he never fumbles. They are not figures of a stage Arcadia, they are not gargoyles mouthing a grotesque dialect, they are the central and imperishable Scot, the Scot of Dunbar and Henryson and the Ballads, as much as the Scot of Burns and Galt and Stevenson. He gives us every variety of peasant life – the sordid, as in the conclaves of Mrs Mailsetter and Mrs Heukbane; the meanly humorous, as in Andrew Fairservice; the greatly humorous, as in Meg Dods; the austere in Davie Deans; the heroic in Bessie McClure. It is this last aspect that I want you to note. Because he made his plain folk so robustly alive, because his comprehension was so complete, he could raise them at the great moment to the heroic without straining our belief in them. No professed prophet of democracy ever did so much for the plain man as this Tory Border laird. Others might make the peasant a pathetic or a humorous or a lovable figure, but Scott could make him also sublime, without departing from the strictest faithfulness in portraying him; nay, it is because of his strict faithfulness that he achieves sublimity where others only produce melodrama. We are familiar enough with laudations of lowly virtue, but they are apt to be a little patronising in tone; the writers are inclined to enter “the huts where poor men lie” with the condescension of a district visitor. Scott is quite incapable of patronage or condescension; he exalts his characters at the fitting moment because he knows the capacity for greatness in ordinary Human nature. It is to his peasants that he gives nearly all the most moving speeches in the novels. It is not a princess or a great lady who lays down the profoundest laws of conduct; it is Jeanie Deans. It is not the kings and captains who most eloquently preach love of country, but Edie Ochiltree, the beggar, who has no belongings but a blue gown and a wallet; and it is the same Edie who, in the famous scene of the storm, speaks words which, while wholly and exquisitely in character, are yet part of the world’s poetry.

⬆︎ Click here for high-resolution version.

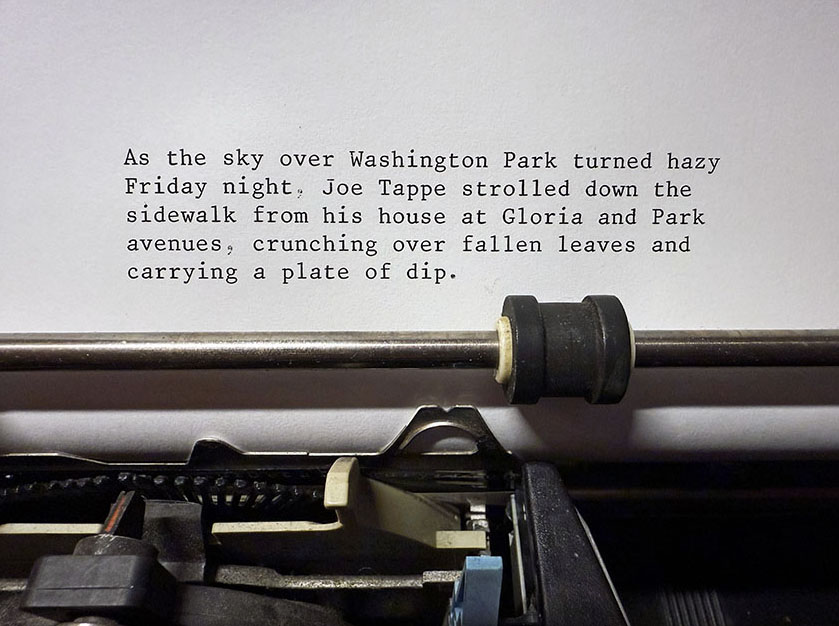

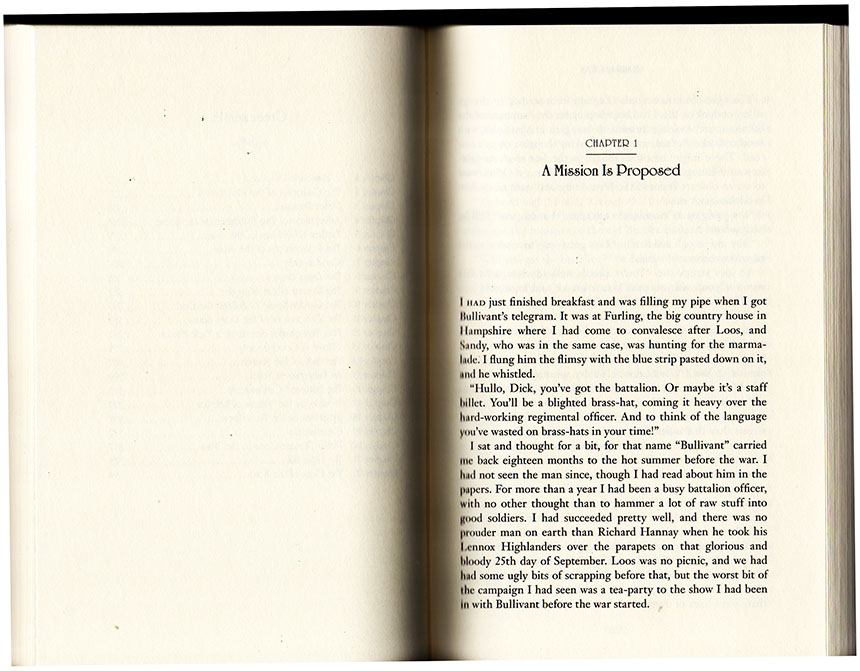

⬆︎ The first page of Greenmantle. Click here for high-resolution version.