When Charles Dickens was a young man, he would sit on London Bridge and watch the traffic — the people on the bridge, the ships on the river. Though London was a somewhere rather than a nowhere, it’s easy to imagine that Dickens thought of the faraway places to which the ships were bound, or from which they were coming. In David Copperfield, Dickens’ young hero does the same thing:

“[B]ut I know that I was often up at six o’clock, and that my favourite lounging-place in the interval was old London Bridge, where I was wont to sit in one of the stone recesses, watching the people going by, or to look over the balustrades at the sun shining in the water, and lighting up the golden flame on the top of the Monument. The Orfling met me here sometimes, to be told some astonishing fictions respecting the wharves and the Tower; of which I can say no more than that I hope I believed them myself.”

A common theme in literature is stories that start nowhere but take the reader somewhere as the plot unfolds. Often the stories return to nowhere at the end (because there’s no place like home). One of the reasons we read is to escape the nowhere in which most of us live for a vicarious look at somewhere.

Through the miracle of the global network that we call the Internet, there are new ways of sitting in the stone recesses of London Bridge and watching the world go by. When I discovered the YouTube live stream from London’s Heathrow Airport, I spent an embarrassing amount of time, as though mesmerized, just watching the planes land, one after another, about a minute apart. The chat window identifies the plane and says where it came from — Buenos Aires, maybe, after a long flight, or Edinburgh after a short one — sometimes places I have never been, sometimes places I remember, and sometimes places that I still would like to go.

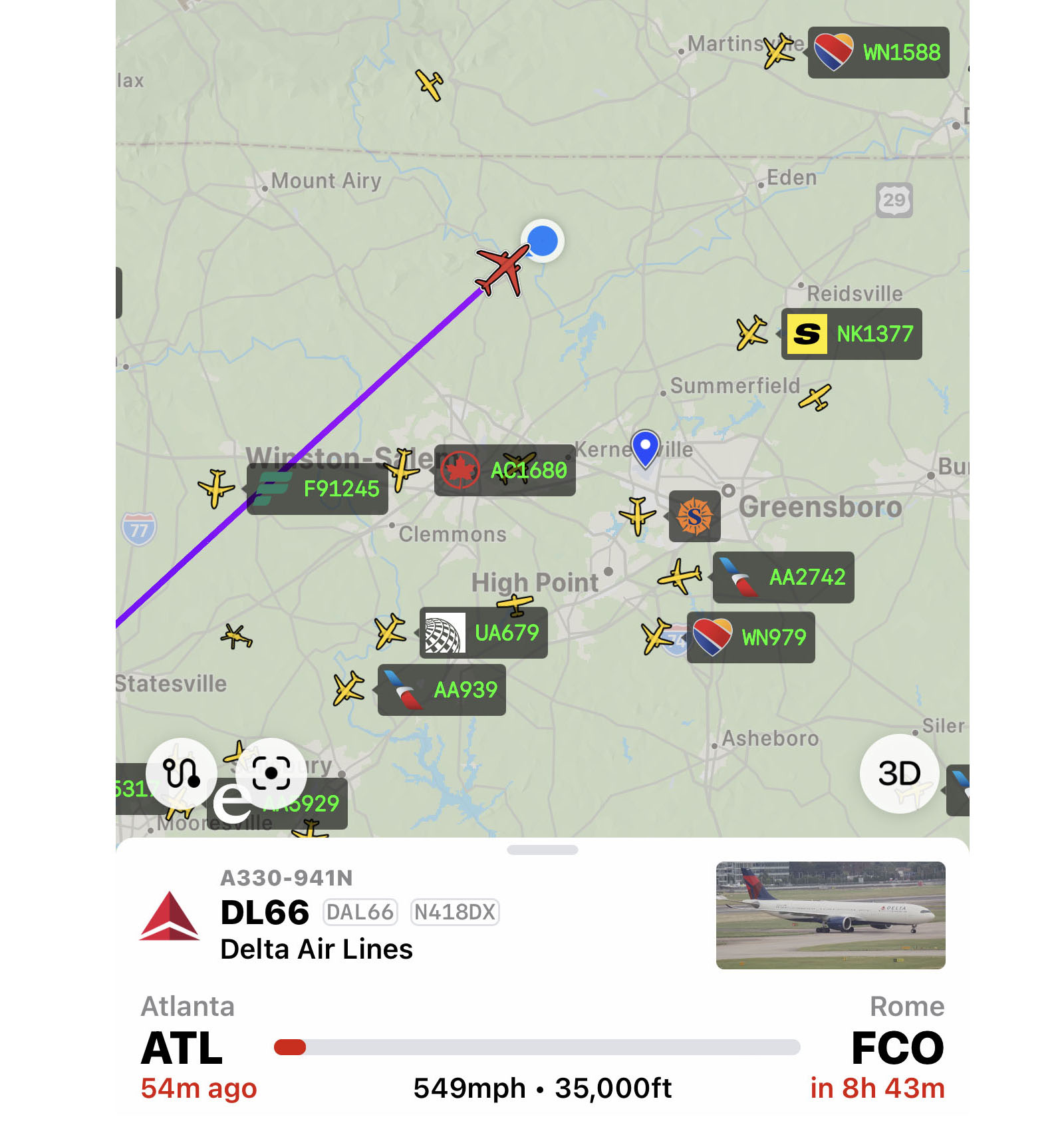

Then I realized that planes fly over my little piece of nowhere all the time. I also realized that there are apps that can identify those planes as they fly over and reveal where they came from and where they are going. It happens that a great many planes in and out of Atlanta fly right over me on the way to Europe and beyond. In no time at all, I saw (in the app) a plane on its way to Paris that was headed my way. I went out to see if I could see it. My eyes never found it, but I heard it pass over. Paris! Until Notre Dame caught fire, I had not planned to ever go to Paris again. Now I want to see Notre Dame after it has been repaired. Then there was a flight to Rome, a big Airbus that made so much noise that I could hear it through my bedroom window.

The YouTube streaming service from Heathrow is Flight Focus 365. The URL changes a couple of times a day, so you’ll need to select the live stream from the list of videos.

The app, for iPhone and Android, is Plane Finder.

Update:

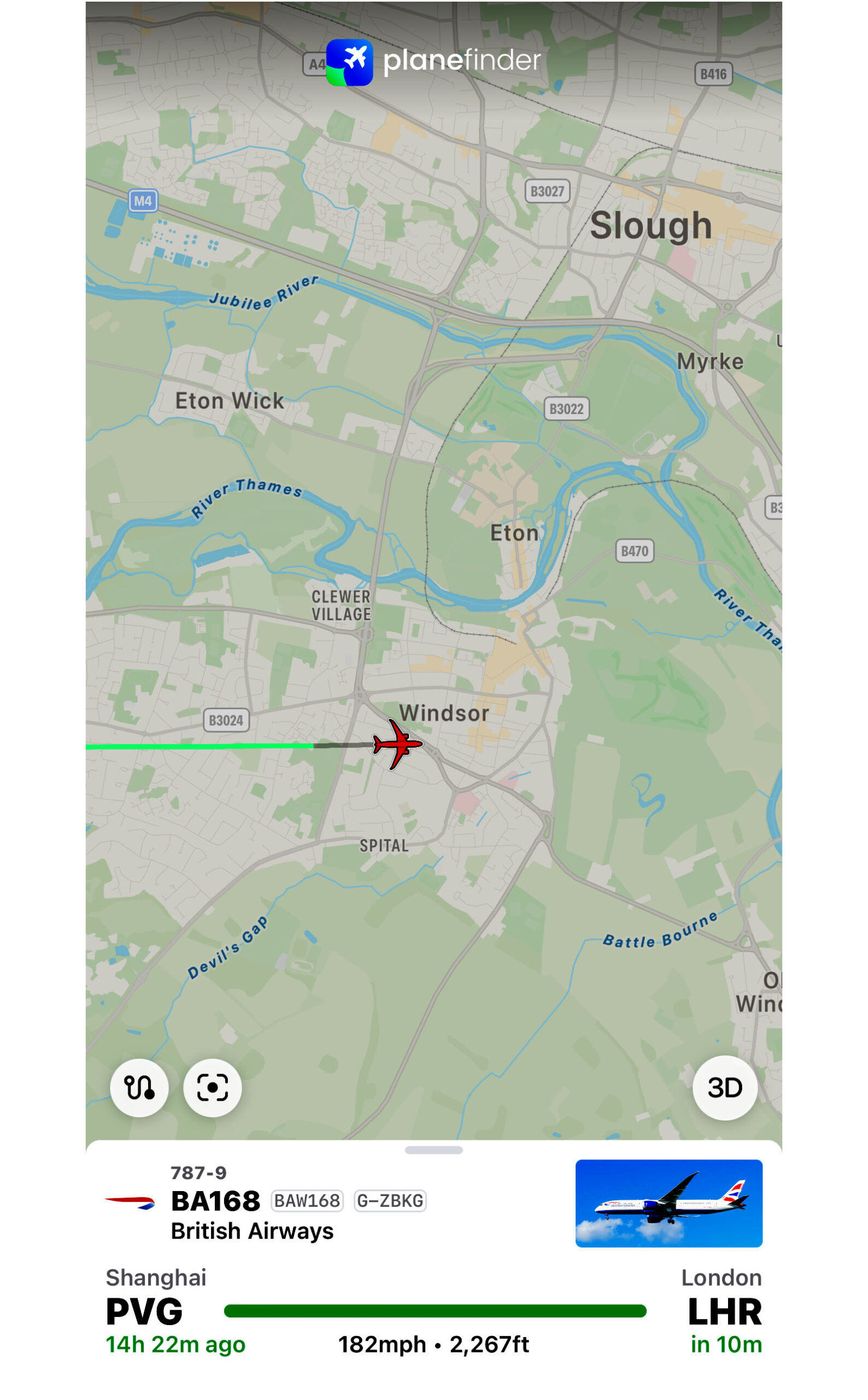

As long as we’re talking about Heathrow Airport, I should mention Windsor Castle. Planes approaching Heathrow from the east pass right over Windsor when they’re about six miles from Heathrow. The altitude is low, a little more than 2,000 feet, so if you’ve got a window seat you’ll get a very good look at Windsor Castle. There are stories that Queen Elizabeth II was so accustomed to the sound of airplanes overhead that she could identify airplanes from their sound.

I should also mention Slough, which is visible in the map below. I had wondered how “Slough” is pronounced. The train toward Paddington Station stops at Slough about 25 minutes before Paddington Station. According to the automated voice that calls out the stops, “Slough” rhymes with “how.”

Just following your blog posts is an education in and of itself. Thank you.

I feel the same David. When I was a child I loved visiting airports and seeing all the exotic-sounding destinations on the departure board (which in those days was one of those mechanical flicker boards)

Slough has a long being the butt of jokes as home to the archetypical dull trading estate. John Benjamin wrote an unflattering poem in the 1930s (‘come raining bombs fall on Slough…) and many years later it became the setting for the comedy series The Office.

Hi Chenda: Of course I had to look up the poem. 🙂 I couldn’t help but think that “Slough” is an unappealing name for a place. But the poem is merciless!

Slough

By John Betjeman (1906-1984)

Come friendly bombs and fall on Slough!

It isn’t fit for humans now,

There isn’t grass to graze a cow.

Swarm over, Death!

Come, bombs and blow to smithereens

Those air-conditioned, bright canteens,

Tinned fruit, tinned meat, tinned milk, tinned beans,

Tinned minds, tinned breath.

Mess up the mess they call a town–

A house for ninety-seven down

And once a week a half a crown

For twenty years.

And get that man with double chin

Who’ll always cheat and always win,

Who washes his repulsive skin

In women’s tears:

And smash his desk of polished oak

And smash his hands so used to stroke

And stop his boring dirty joke

And make him yell.

But spare the bald young clerks who add

The profits of the stinking cad;

It’s not their fault that they are mad,

They’ve tasted Hell.

It’s not their fault they do not know

The birdsong from the radio,

It’s not their fault they often go

To Maidenhead

And talk of sport and makes of cars

In various bogus-Tudor bars

And daren’t look up and see the stars

But belch instead.

In labour-saving homes, with care

Their wives frizz out peroxide hair

And dry it in synthetic air

And paint their nails.

Come, friendly bombs and fall on Slough

To get it ready for the plough.

The cabbages are coming now;

The earth exhales.

It really is! I hadn’t realised it was published just a few years before bombs did actually fall on Slough. My mum grew up in neighbouring Uxbridge so I am somewhat familiar with the area. It is quite boring, but there certainly worse places 🙂

There’s a Wikipedia article about the poem. It seems that later in his life he felt very bad about having written the poem.