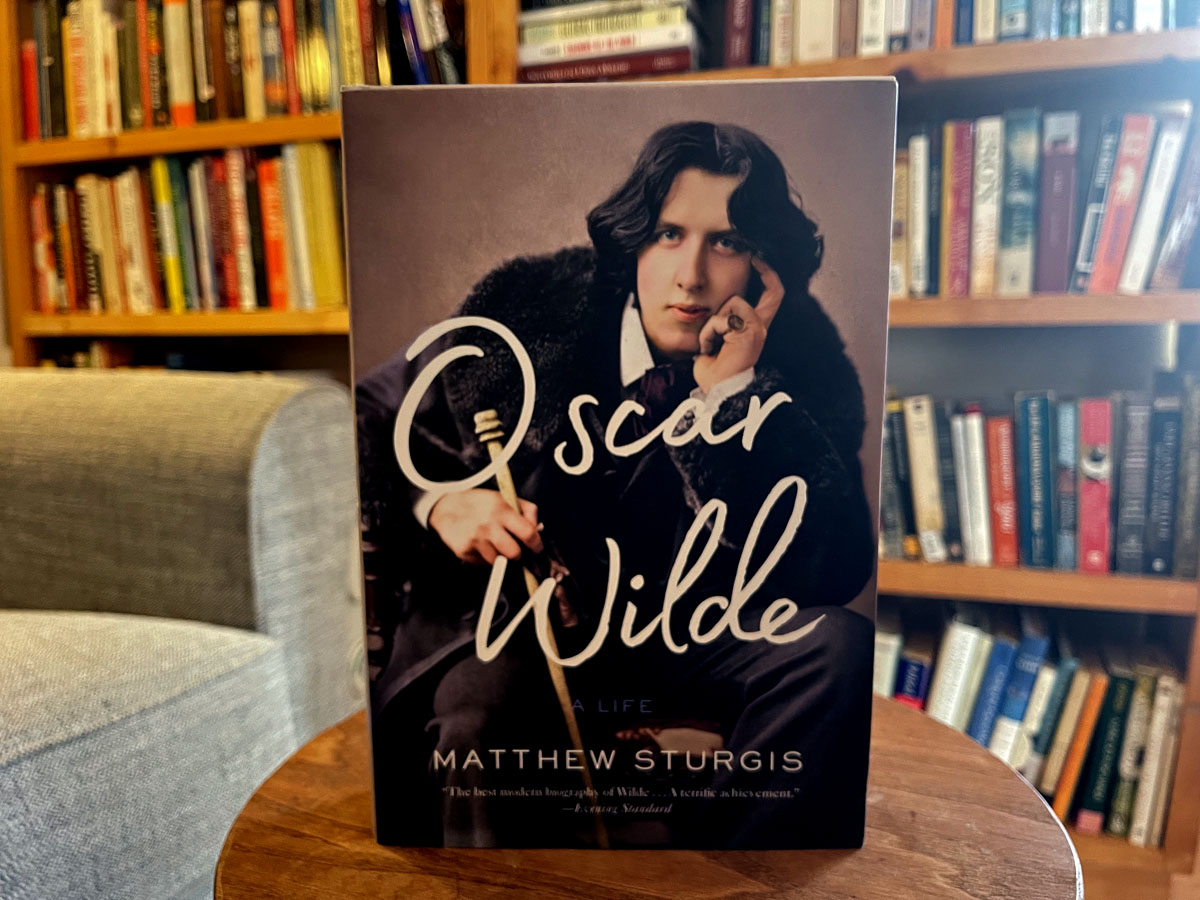

Oscar Wilde: A Life. Matthew Sturgis. Alfred A. Knopf, 2021. 838 pages.

It’s an important question, and there probably are many answers: A hundred and twenty years after his death, why does the life of Oscar Wilde still matter, and why does Wilde interest us so much today? This is the second vast biography in 30 years. Richard Ellman’s biography (1988) still sells and was a fine piece of scholarship. Sturgis’s biography is even better.

Sturgis offers no opinions on why Wilde matters until the four-page epilogue. Wilde matters today, Sturgis says, because he was right about a lot of things.

The tragedy was that Wilde was born into the wrong place and time. Even at the time, France and Italy would not have destroyed Wilde the way England did. France and Italy were often refuges for Wilde, though they were not places where Wilde could have become famous.

At times while reading this book, I wanted to scold Wilde. Clearly he was vain, and much of his posings, posturings, and sayings were a show driven by the desire for fame. Again and again he made ridiculously bad decisions. He was clueless about how to handle money. If you add up what Wilde earned versus what he squandered (not just money), then the squanderings at the time of Wilde’s pathetic death (Nov. 30, 1900) surely exceeded the earnings — except for the fact that Wilde left a legacy that we continue to value today. I don’t recall that Ellman was clear about the fact that Wilde was born to enormous privilege. Sturgis tells us much more about Wilde’s aristocratic origins in Ireland and the open doors for Wilde at Oxford. Much should be expected out of so much privilege.

And yet foibles aside, Wilde comes across, always, as a kind, generous, and very decent human being. When he damaged others — as he certainly did with his family — it was always out of blindness for which he subsequently repented (and often relapsed), never wilful malice. There were many people of high achievement who saw Wilde as a fraud but who, after talking with him, had to concede that Wilde was a superb scholar and a more genuine person than they had supposed.

The villains in this story are the Victorians. The ogres are a few horrible people such as Lord Alfred Douglas and his father, John Douglas, the 9th marquess of Queensbury. The saints are people such as Constance, Wilde’s wife, who died a few months before Wilde died, probably from grief and shame. Another saint is Robbie Ross, who stuck with Wilde until the end and who, as Wilde’s literary executor, did much of the work than preserved the record of Wilde’s life and works.

In 2017, the Queen of England pardoned Wilde, along with 75,000 other Britons who had been convicted under the abolished laws that sent Wilde to prison and led to his death. That took almost 120 years. What a sorry race of human beings we white people are, even if we’re slowly getting better.

I’ll venture one other thought on why Oscar Wilde still matters. It’s that the Victorians are still among us, and that the work that Oscar Wilde bravely started remains incomplete. If Wilde’s life was a warning to other misfits about how to live in the wrong place at the wrong time, other lives in this story are models — Robbie Ross, for example, with his loyalty, integrity, and his talent for salvaging as much as possible from catastrophe.

The Importance of being Ernest was the only play I actually really enjoyed reading at secondary school (which says as much about the school as it does the play) but it left me with a good impression of Wilde.

Did you ever hear of a guy called William Beckford David ? I don’t wish to equate him with Wilde (for a number of different reasons) but he was an interesting and scandalous figure a few generations before Wilde. He wrote a gothic novel and built Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire, an absurdly vast gothic mansion bigger than many cathedrals. It collapsed under its own weight after a few years but it was a remarkable piece of architectural fantasy, its hard to believe it actually existed.

Hi Chenda: I had not heard of William Beckford, but I just read the Wikipedia article. What a house! I would read Valthek if it were set in England!