Source: Hubble telescope, NASA, Jesœs Maz Apellÿniz, and Davide De Martin via Wikimedia Commons

An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics. Bradley W. Carroll and Dale A. Ostlie. Cambridge University Press, 2017. 1,342 pages.

Quick now: How old is the universe? Answer: About 13.8 billion years.

If you were to walk out under the night sky this evening, photons of light would reach you that are billions of years old. You wouldn’t be able to detect those photons with your unaided eyes, but the photons came from the far edges of the observable universe. That light is very, very old and was generated by a star that was among the first to form after the Big Bang. When you look out into the far reaches of the universe, you are looking into the distant past. Even the light from our sun, of course, is about eight minutes old. What’s happening at the edges of the universe right now? We can’t possibly know for billions of years, when the light reaches us.

It is almost criminal that light pollution and modern living have robbed us of a relationship with the stars. Our ancestors must have felt that relationship very keenly, given some of the artefacts they left — the clay tablets of the Babylonian astrologers and astronomers, for example, or the prehistoric henges.

One of my favorite bedside books is an astronomy textbook last revised in 1964. There’s very little in that textbook that is actually wrong; astronomers then knew what they didn’t know and what needed to be figured out. But in the 55 years or so between the two textbooks, our knowledge of astrophysics has exploded. There are very few equations in the 1964 textbook, but the 2017 textbook is full of them. We now have mathematical models for (and therefore substantial understanding of) all sorts of phenomena, including what happens in the interior of stars, how elements heavier than hydrogen are formed inside of stars, how gravity works its magic in the gas and dust of the interstellar medium to form galaxies, etc. Astrophysicists love their equations.

I cannot follow the math of all those equations. However, not being able to follow the math should not stand in the way of reading books like this. I frequently read books that I can’t completely understand. There is still much that can be learned. The processes that are modeled by equations can also be described in text, and this book is lucid in its descriptions of astrophysical phenomena.

But, as is often the case with nerds, it’s not just about the science. The wonders of the universe also are food for the imagination. I can almost imagine that stars have personalities. Though stars can be classified according to type, size, age, temperature, and many other factors, each star is different. There are even not-exactly-fringy theories that stars are conscious. Stars, like life, have the almost magical ability to create order in a chaotic universe. Stars can do amazing things, such as make oxygen or iron or gold out of hydrogen. Stars furnish the chemicals out of which life is made and the energy that sustains life. Like stars, each galaxy also is different. Both stars and galaxies cluster, almost as though they have social needs. Stars (and galaxies) are very frequently found in pairs like friends or lovers, orbiting each other around their mutual center of gravity. Like us, stars are born. Some live longer lives than others, but eventually all stars die. The earth, of course, is made from the bodies of long-deceased stars, which is why scientists like to point out that we are all stardust.

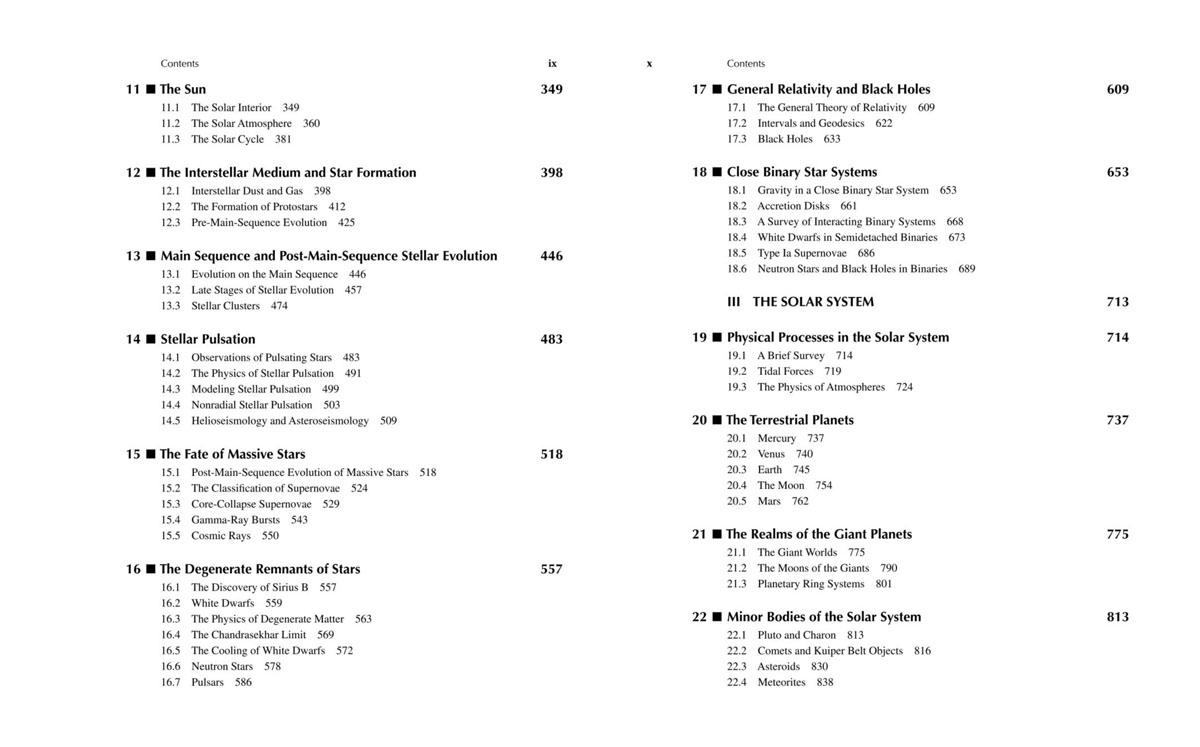

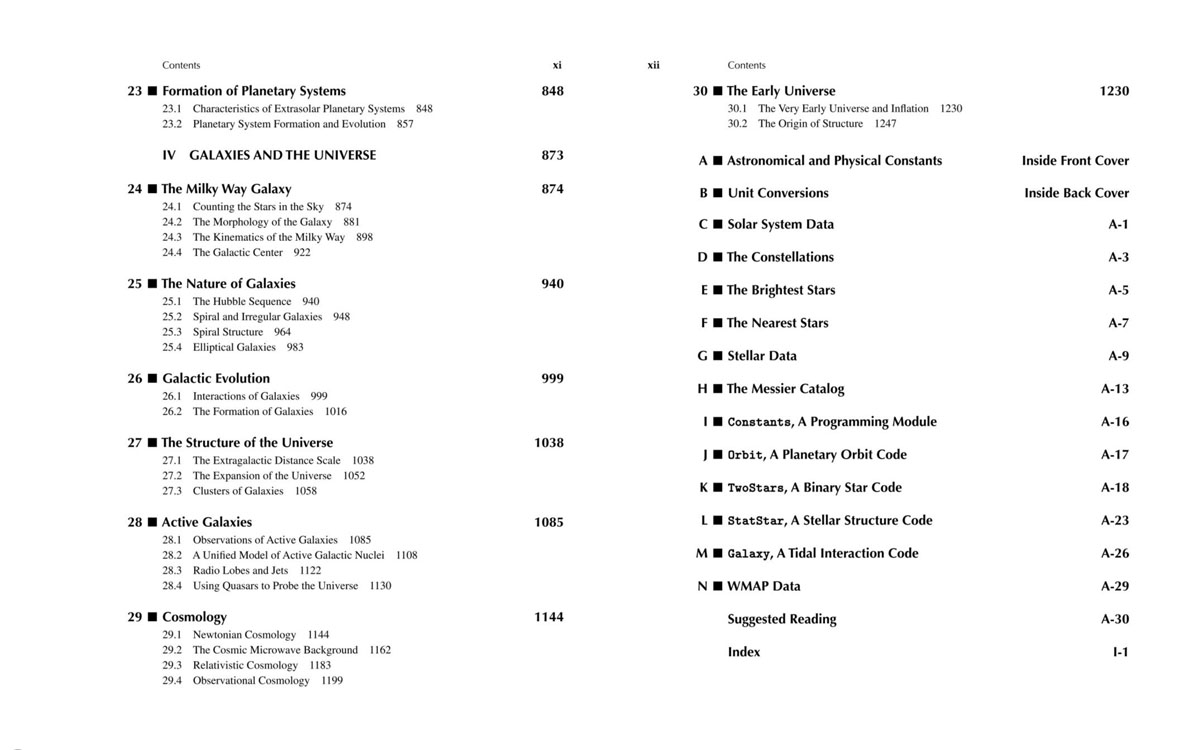

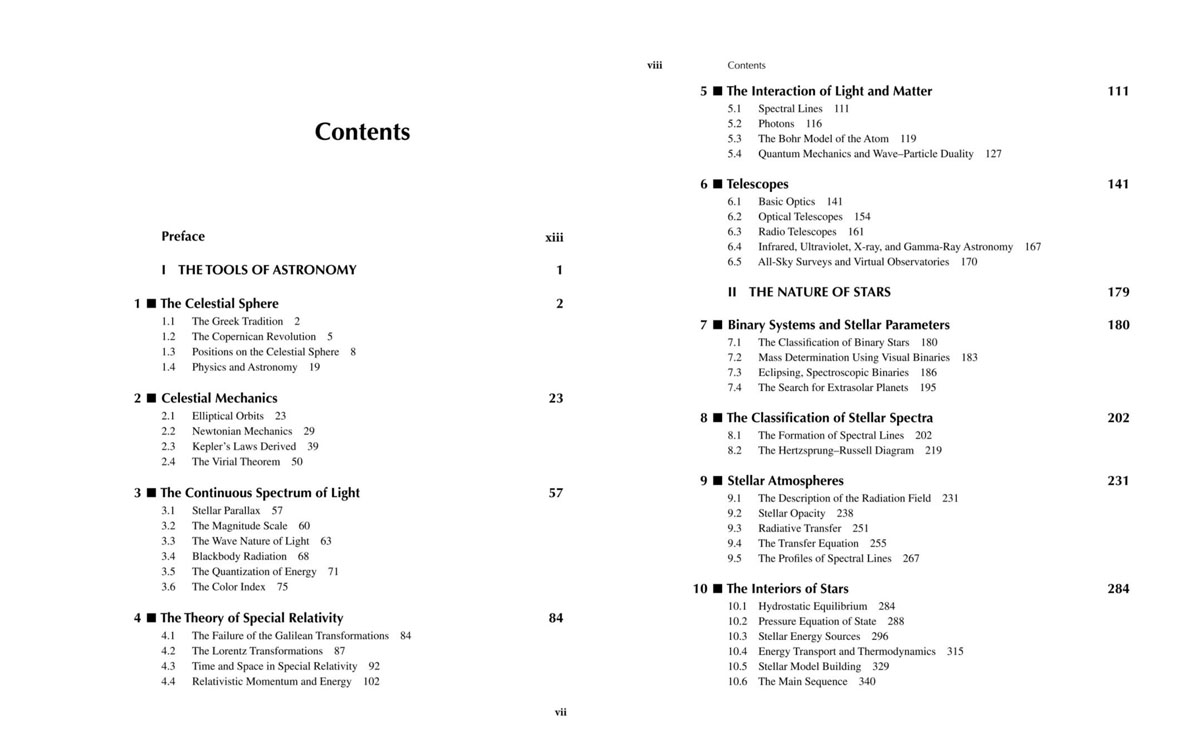

The table of contents of this book is an excellent outline of what we know so far about the universe.

Cambridge University Press. Click on images for high-resolution version.