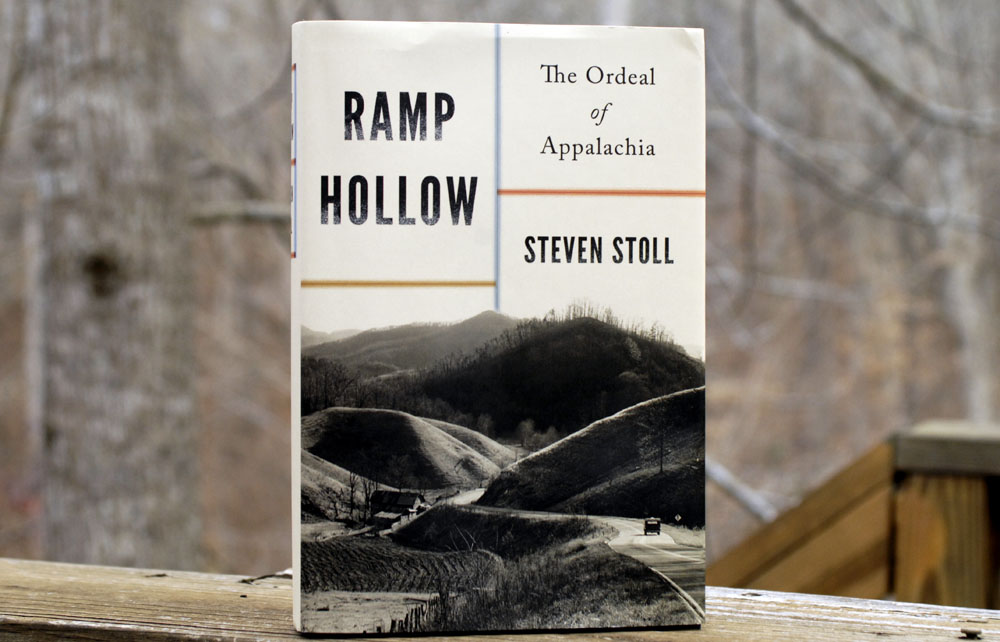

Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia, by Steven Stoll. Hill and Wang, 2017. 412 pages. ★★★★★

During the past couple of years, an extraordinary series of books have brought to our attention just what a sorry state the world is in. Ramp Hollow is the latest. Some of the others (many of which I have reviewed here) are:

Thomas Piketty: Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Anthony Atkinson: Inequality: What Can Be Done?

Kyle Harper: The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire

James C. Scott: Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States

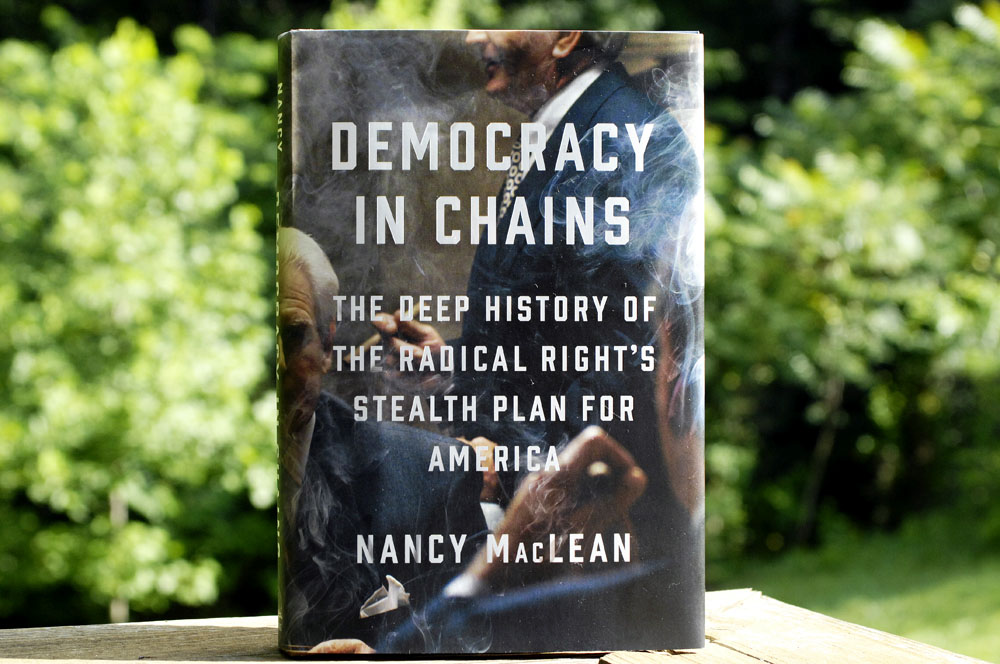

Nancy MacLean: Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America.

Jason Stanley: How Propaganda Works.

Sebastian Junger: Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging

Jason Brennan: Against Democracy

Volker Ullrich: Hitler: Ascent, 1889-1939

Jack Rakove: Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America

This is by no means a complete list. There are others that I still urgently need to read, including books by George Monbiot and Jonathan Haidt.

Stoll is a professor of history at Fordham University.

As for Ramp Hollow, I used the word “angrifying” in an email to a friend. I subsequently came across a review that used the word “enraging.” This book is a history of how the self-sufficient subsistence farmers of Appalachia were dispossessed of their land by the timber and coal industries and forced to work in coal camps and mill towns for starvation wages. Their forests and swidden fields, which they depended upon for their living, which were a kind of commons, were enclosed and decimated to feed the industrial revolution.

Stoll has much to say about dispossession and enclosure in general, starting in England in the 17th Century when Parliament dispossessed the rural English of their common lands, gave the land to the lords, enclosed the land, and forced the people to become peasants who worked the land for others. Earlier in American history, the native Americans had been dispossessed by the colonists. After the Civil War, every possible effort was made to keep emancipated blacks dispossessed, landless, and forced to work like slaves for others. All this was seen as economic and social progress. The poverty and misery this so-called progress caused was hardly noticed.

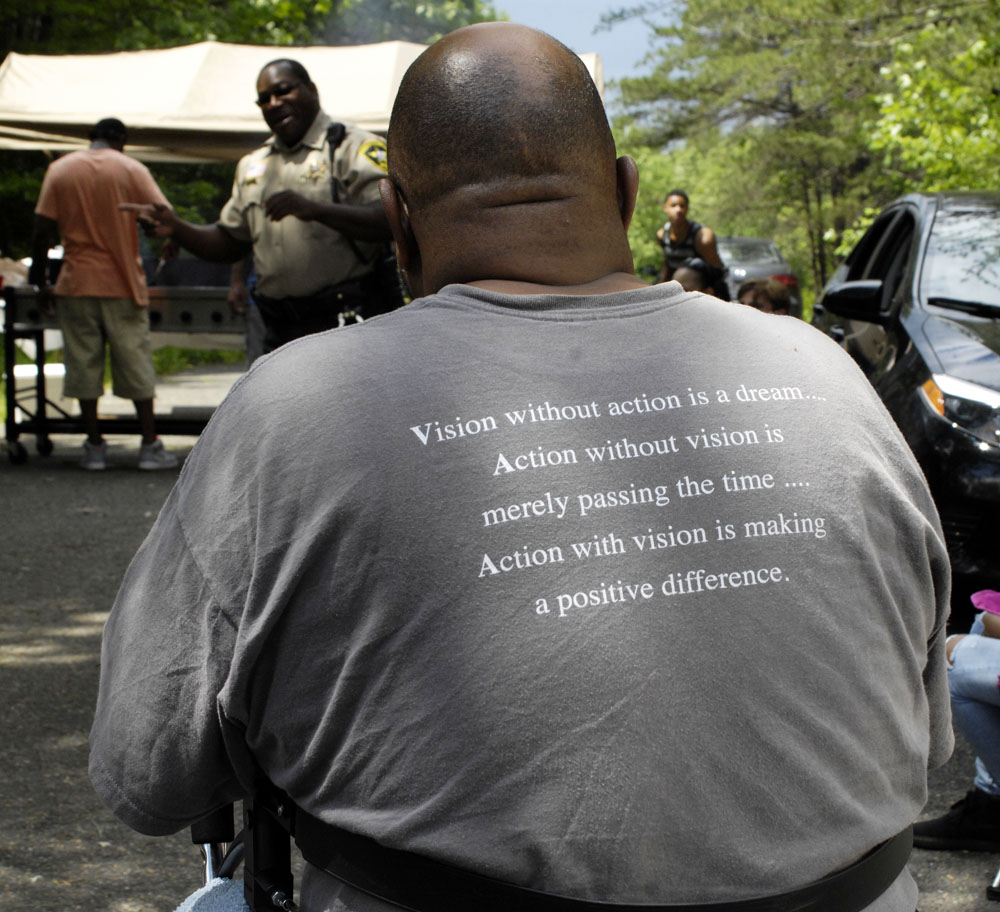

All around us today, we see the consequences. The poor people who now spend much of their sorry wages buying health-destroying foods at Dollar Generals are descendants of people who once lived off the land with no need of wages. The old subsistence farmers liked money when they could get it, but they could live without money. They traded with each other for what they could not make or grow themselves. Their descendants are dependent on money and sorry wages. They buy their sorry food from corporations.

We have forgotten how forests provided a living. The abundance produced by forests goes far beyond hunting or gathering nuts. One burned a little piece of forest and planted one’s crops amid the stumps. Pigs could live in the woods without being fed. Chickens did fine with a little bit of woods, a little bit of clearing, and a little stream from which to drink. With some pasture, you could keep a cow. Capitalism, on the other hand, saw the forests only as a source of timber to be clear-cut and shipped out by train. Beneath the West Virginia forests lay coal. Capitalism could not tolerate people living without money. Dispossession was a win-win for capitalism. The timber could be sold, and the people who were forced off the land were now a source of cheap labor and taxes, dependent on money for a living rather than on their environment.

Stoll’s book is an unapologetic indictment of capitalism. He ends the book with a stunning proposal — he calls it a thought experiment, but it would be doable if we had the political will — for reversing the centuries-old process of dispossession and the poverty and inequality it has caused. He calls it “The Commons Communities Act.” I’m all for it.

This book is enraging because it tells the story of cruelties and injustices that history did not record:

Those who hung on in the hills had their misfortunes thrown back at them. The basis of their autonomy gutted or sold, they pecked and scrimped. The words of the engineer who condemned them in 1904 echo here: “forlorn and miserable … never having known anything better than the wretched surroundings of their everyday life.” Though they often insisted that they could make a living on remnants of the old commons, they had become poor. They had become the horrifying hillbillies that lowlanders had always thought them to be.

The story is an old one: The intentional creation of poverty by the rich, in order to exploit the labor of the poor. Today’s rich have become so sophisticated at this exploitation that their propaganda has turned its dispossessed victims into active agitators for their own greater exploitation. The very idea of taxing the rich for the relief of the poor is rejected with a religious fervor. How long can this go on?