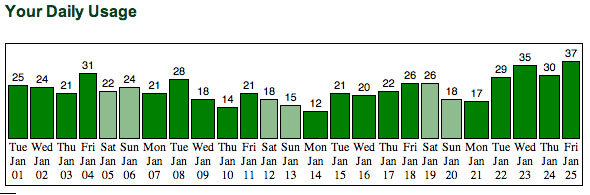

The green bars show my daily electricity usage for January in kilowatt hours. Below: a smart meter.

A year or two ago, my electric company — a regional electric coop named Energy United — installed “smart meters.” The purpose of these meters is to save the power company money, because no one has to be sent around to read them. The meters call home over the electric lines, reporting data back to the power company. Not to mention letting the power company know if your power is out, and automatically tracking widespread outages.

But this calling home doesn’t happen just once a month. It’s a regular thing. This allows the power company to track daily usage of electricity and report it to their customers on their web site.

I’m almost obsessive in collecting data on my electricity usage. I keep records of the abbey’s electrical usage in a spreadsheet, going back to when the lights at the abbey first came on in June 2009. When the weather is exceptionally cold, as it has been at times this month, I like to see how many kilowatt hours it takes to get through a really cold day.

Yesterday, January 25, was such a day. The low was 16F when the day started, and 19F when the day ended. The temperature did not rise above freezing all day, and snow and ice pellets were falling. I used 37 kilowatt hours yesterday. That covered the heat pump’s usage, plus my normal electrical usage. My stove is electric. I baked bread and did a lot of cooking yesterday. I also kept water boiling in a kettle for part of the day to raise the humidity in the house. My electrical cost for the day was $2.82. If I look at kilowatt-hour usage for the lowest-usage day of January (when I used very little heat) and do the arithmetic on the difference, I calculate that my heating cost yesterday was $1.91, while the remaining $0.91 was for other electrical usage.

This blows my mind. Partly it’s that electricity rates are low in North Carolina compared with some other areas, and partly it’s that the abbey is a very efficient building and isn’t too big (1,250 square feet). Plus the heat pump, a Trane unit of the same age as the abbey, is pretty efficient. Heat pumps are by far the most energy-efficient source of heat, though they lose efficiency when the outdoor temperature is low. When the outdoor temperature is, say, 45 degrees, a heat pump is about four times more efficient than when the outdoor temperature is, say, 16 degrees. It is, after all, capturing heat from the outside air and pumping it into the house, so they don’t work as well in cold weather. All heat pumps, as far as I know, having heating coils that kick in if the outdoor compressor can’t produce enough heat. They really are quite amazing machines, and modern heat pumps are much more efficient than the heat pumps of 20 or 30 years ago. Modern heat pumps also use ozone-friendly gases. The old freon systems are getting old and are rapidly being replaced.

These calculations led me to a thought experiment. What if that heat had come from, say, gasoline rather than electricity. If the gasoline had cost $3.69 a gallon, then the $2.82 would have bought me three-quarters of a gallon of gas. The cost of the heating portion of my electricity equals half a gallon of gas. That means that I heated the abbey on the coldest day in January for the amount of energy (calculated according to cost) that it would take to drive an SUV about 8 or 9 miles! How the carbon load compares may tell a different story, but that’s a calculation for another day.

I plan to do a future post on how I’ve used my energy consumption data to roughly calculate my carbon footprint. We all should know what our carbon footprint is.

Note: The abbey has a propane fireplace, and I did use the fireplace some yesterday for the entertainment of myself and the cat. However, the BTU output of the fireplace is much less than the house’s heating system, and the fireplace is never used at night, when the heating system works hardest. Though the fireplace contributed some heat yesterday, the amount of that heat would be minor compared with the heat provided by the electric heat pump system.