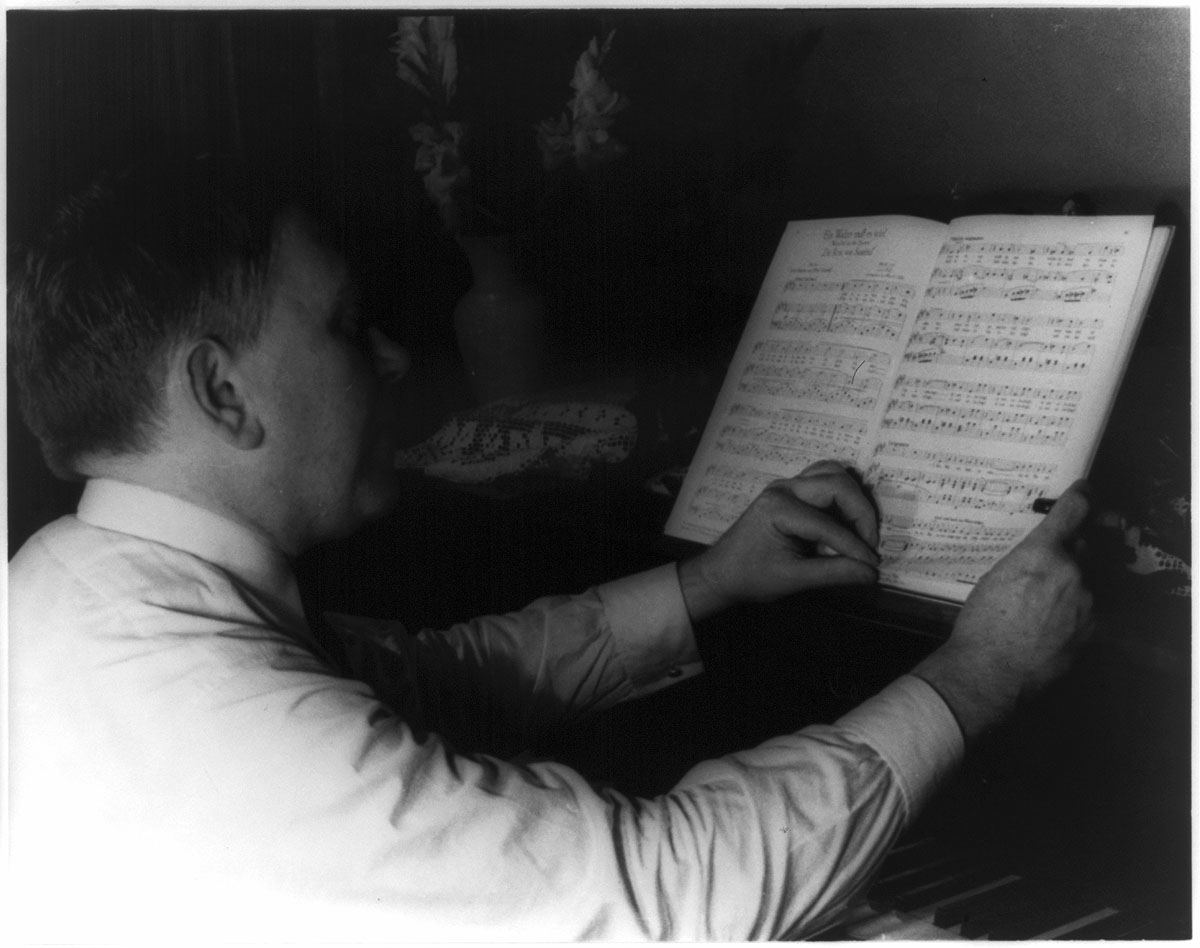

H.L. Mencken. Portrait by Carl Van Vecten, 1932, Library of Congress

To see similarities between snark and gun violence is wrong of me, I admit. Both are epidemic. But one is deadly, and the other merely wounds. But I had been thinking about two different posts that I might write here, one on snark, and the other on shooting guns (forthcoming, later). In that state of mind, I came across a long piece in this morning’s New York Times by Gregory Gibson. The piece is A Gun Killed My Son. So Why Do I Want to Own One?

The piece is beautifully written. It reflects the soul-searching and self-awareness that the author has gained in his years-long quest (it definitely was a quest) to come to terms with the senseless, wasteful death of his son, a college student. But, if you read this piece, don’t expect a clear conclusion wrapped in vellum and tied with string. It’s a lot of questions with few, if any, answers.

So it is with irony, snark, and smarm. A lot of culture pieces have been written on these three things in the past twenty years. You can take sides if you want, just as you can take sides on the heated subject of gun control. Or, like the author of the gun piece in this morning’s New York Times, you might see that, the closer you look at the subject, the more complicated it becomes.

The cultural warfare over irony, snark, and smarm started around 1999 with a young man named Jedediah Purdy. We first heard about Purdy in a New York Times article, “Against Irony,” that was published on Sept. 5, 1999. Not long after that, when Purdy was only 24, his first book was published, For Common Things: Irony, Trust and Commitment in America Today. Almost overnight — among the literati, anyway — the subject of irony became a battleground, like gun control. There were those who wanted to (and did) rip the liberal and kind-hearted Purdy to shreds with snark and irony. And there were those (like me) who have followed Purdy’s career ever since.

It was more than ten years later when Purdy took a direct hit from a nuke dropped on him by Tom Scocca. The piece was “On Smarm,” published at Gawker in December 2013. It’s a long piece, and Scocca expends quite a few paragraphs to take Purdy apart with snark. I’ll quote only the first and last paragraphs here:

First paragraph:

A Fable From the Age of Smarm: Once upon a time, in the high hills of West Virginia, there lived a young man named Jedediah Purdy. Jedediah was fond of animals and of taking long walks through the woods; he liked to eat fruit that was not entirely ripe. His parents had gone into the hills to get away from electricity and the corruptions of civilization, to raise their children apart from “the hollowness of mainstream living,” as the New York Times Magazine put it. They built their own home and slaughtered their own pigs.

Last paragraph:

Jedediah Purdy is now a professor at Duke Law [later Columbia] and has been a visiting professor at Yale Law, the school at which he got his own J.D., after he graduated from Harvard, after he graduated from Exeter. For this, pigs were butchered. Such are the fruits of renouncing the mainstream.

Personally, I find Scocca as irksome as Scocca finds Purdy. But I must agree with Scocca that irony — and even its weaponized version, snark — can serve (like guns) a noble and defensive purpose if in the right hands. However, no background check and permit are required to employ the weapon of snark against people. Anyone can do it.

Scocca reminds us of the enduring power that snark and irony can have when discharged by those who are morally sane and gifted as writers:

One curious fact about this long view is that it’s quite untrue. I can’t recall ever, unless compelled by duty, rereading a Malcolm Gladwell article. What I have reread is Mencken on the Scopes Trial, Hunter Thompson on Richard Nixon, and Dorothy Parker on most things—to say nothing of Orwell on poverty and Du Bois on racism, or David Foster Wallace on the existential horror of a leisure cruise. This belief that oblivion awaits the naysayers and the snarkers shouldn’t survive a glance at the bookshelf.

If it’s true that there is no defense against an idiot with a gun other than a non-idiot with a better gun, then it’s also true that there is no defense against an idiot with snark other than a non-idiot with better snark. Though I have done my best to stay away from places (and people) in social media where the snark flies like bullets, not infrequently I still find myself caught in the crossfire, or hit with a stray round of snark. What do I do? I fire back almost as a reflex. I’m a sharpshooter when it comes to snark.

But I do wish to draw a line. Just as we (we Americans, anyway) live in a gun culture, we also live in a snark culture. But, for the sake of our mental health (and our relationships), we’d better have some safe space. We all need people in our lives who not only will never use irony and snark against us, but who also will come to our defense.

I have spent a great deal of time over the years editing not only what I have written myself, but also what others have written. Post-Purdy, I have developed an editing mode that I call “snark detecting.” Most of the time (and here I find myself agreeing with those whom Scocca berates as smarmy) I find that snark and irony greatly weaken a piece of writing. I often quote a friend who is a very fine writer as saying that there is no sin for a writer worse than insincerity. Except for those emergency occasions when some snarky idiot needs to be lit up, outsnarked, and taken out of action with superior snark, I think we’d all do well to employ our snark detectors and edit out the snark.

Writers and editors often talk about tone. But we are all writers now, because we all use email. Tone can be difficult to control. When writing anything that could be touchy, I try to take the time to reread what I’ve written just for tone. For example, consider this line, which is taken from an actual business email sent to me relating to a publishing project:

Do we need to talk, again, about division of labor?

Note how the two commas around the word “again” change the tone from reasonably neutral to remonstrative and slightly snarky. Yes, I took offense (though I did not respond with snark).

I have a not-exactly-tacit agreement with one of my friends to never use irony with each other, let alone snark. In fact, several years ago, when in a casual remark he employed a touch of irony (not against me, though) I didn’t understand him and had to ask him what he meant. Irony-free zones, I would argue, are necessary for our mental health.

If I have a conclusion, it’s about where I draw the line. I detest irony and snark. These days, irony is as inescapable in our popular culture as snark is in our political culture. (In popular culture, think of “The Big Bang Theory” — all snark all the time, and anti-intellectual snark at that. It was almost violent in its snarkiness. I didn’t find it the least bit funny.) Occasionally I hear couples snark at each other in public, as though we as a society are normalizing the Big Bang theory of relationships. I think to myself, there goes a relationship that is in its last season. Intimacy and supportiveness cannot survive against snark, though society can. And regardless of what it says about me as a person, anyone who snarks at me on Facebook (or at an auto parts store) can expect a blast of snark in return, aimed right between the eyes, because civility is no defense against snark (no matter what they say in smarm school).

If snark was fatal, as guns can be, then I would be pretty dangerous. But I would like to think that I also know when not to use it. I carry snark as a concealed weapon. Outside our safe spaces, where snark flies like the bullets of angry and unstable white men, you never know when you might need it.

An aside: In searching the Internet for photos of one of America’s greatest curmudgeons, H.L. Mencken, I was surprised to find the one above. He is sitting at a piano (who knew?), with an open book of music. A little Googling shows that Mencken was a pianist, and that he played regularly with a group of musicians who called themselves “The Saturday Night Club.” They got together to drink and play music. What is that piece of music on the piano in front of Mencken? No matter how much I zoom in, I can’t read the title. But it looks like German to me. The arrangement is clearly for voice with piano accompaniment. My guess is that it’s a book of Schubert lieder. Knowing that Mencken was a musician helps, I think, to understand why Mencken’s snark and irony were so beautiful and so effective as cultural and political commentary. He was an artist at it.

Sorry to confess, but the only snark I know about is

C.S.Lewis: Hunting of the Snark – lolol

But if wiki’s right in, that ‘snark’s just another work for irony – I prefere the word ‘irony’, cause ‘snark’ is something which doesn’t exist (the fabel animal of Lewis) – lolol.

Irony can be very funny if served the right way 🙂