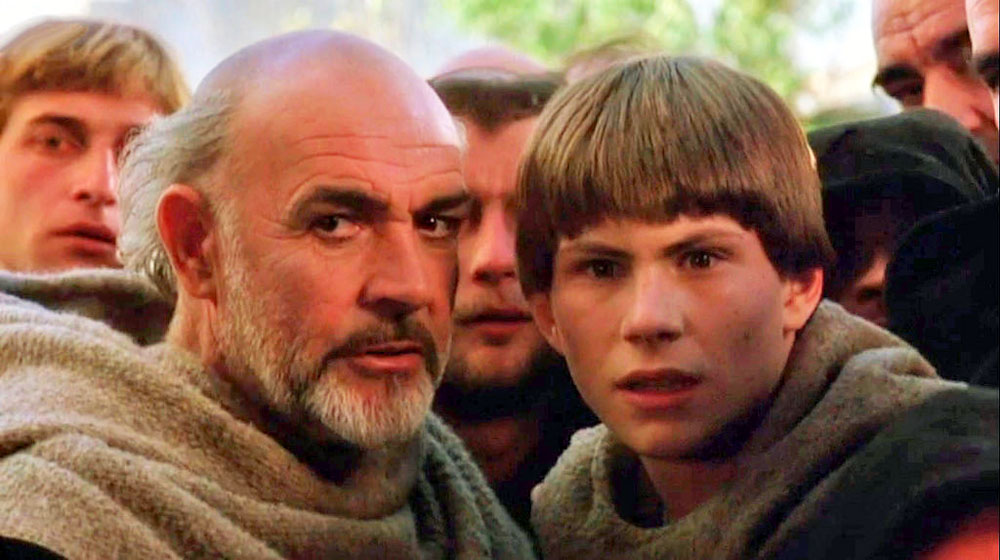

Sean Connery and Christian Slater in “The Name of the Rose”

The Name of the Rose, Umberto Eco, 1980. English translation 1983.

What? I’m reviewing a book that was first published 37 years ago? Oh well. No one ever accused me of being au courant.

I have tried several times in the past to read Umberto Eco’s The Name of Rose, as well as Foucault’s Pendulum. I have always been driven back by the dry wordiness of Eco’s prose. This time I resolved to finish The Name of the Rose no matter how big a chore it might be, partly as an exercise in better understanding why some writers earn far more generous reputations than they deserve.

First, let’s talk about the film, from 1986. Directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud and with a superb cast including Sean Connery, F. Murray Abraham and the young Christian Slater, the film — I thought, at least — was one of the best and most memorable films of the 1980s. But the film didn’t make much money in the United States, though people in more intelligent parts of the world loved it. Roger Ebert wrote, “What we have here is the setup for a wonderful movie. What we get is a very confused story.”

I don’t agree with Ebert. The screenwriters actually did a brilliant job of stripping out most of Eco’s confusion, endless declamation and disquisition, and sticking to the plot — your basic murder mystery. It was said that Eco didn’t much like the screenplay, precisely because all that erudition got cut (as it had to be).

Eco was a scholar — no doubt a good one — with a wide range of interests. The Name of the Rose drew on his background as a medievalist. Obviously Eco was fascinated by the theological debates of the late medieval period. Also obviously, the setting and the plot for The Name of the Rose were chosen because they provided a basis for page after page of theological hairsplitting by monks of different orders. To Eco’s credit, these endless orations on Christian theology can be funny in their absurdity, and Eco leaves it to the reader to discern what fools his monks are. William of Baskerville, however, is at least a nice fool. And his teenage novice Adso (Christian Slater), with his naiveté and surging hormones, is a very fine foil for so much useless learnedness.

(Incidentally, the chief subject of Eco’s theological debate is whether Christ was poor. The Franciscan order certainly believed in the poverty of Christ, and they got crossways with some popes and with the Inquisition. If you’re interested in the details of all that, I’ll leave you to read The Name of the Rose. But it is worth pointing out, I think, how the church is still divided by the question of poverty, with a few Christians remaining who actually care about the poor, and with other Christians giving their money to birdbrain preachers who live in multimillion-dollar mansions like little popes and fly around on the Lord’s business in private jets. If this history repeated itself, then Christians who care today about the poor would be burned at the stake.)

But what I conclude about Umberto Eco is in many ways similar to what I conclude about Neal Stephenson, the science fiction writer. Both, I would guess, are somewhere well along on the autism spectrum. Both are fine thinkers — but without the least trace of feeling. Stephenson, like Eco, set one of his novels in a monastery (Anathem) and for the same reason — so that their characters can talk, talk, talk about abstractions that they find interesting. But their characters, like the authors, totally lack feeling. I also would argue that the best moments in fiction occur when a character is so driven to despair or ecstasy that the character is compelled to sing. When an author sings, that’s when you learn what motivates the author to write in the first place. For a fine discussion on moments in fiction that sing, see E.M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel.

In any case, with writers like Eco and Stephenson, one of the most powerful and meaningful ingredients of good fiction is totally missing. Both Eco and Stephenson are so blind to the feeling element of fiction that they seem unaware of the flatness of their characters and make no attempt to simulate the missing ingredient. Adso knows how to suffer some where sex is involved, but Adso cannot sing.

That said, I love brainy fiction — Isaac Asimov, for example. I have great respect for (and considerable interest in) the erudition to be found in Neal Stephenson’s and Umberto Eco’s novels. But it’s not enough, and that’s a shame.

Wow, fond memories of Tobaccoville. That’s where we first watched it together. Do people even remember VHS video tapes?

I was surprised by your comments about Umberto Eco at first, and then not. I didn’t read the novel and so had know idea about the dry prose. I only saw the movie, which seemed to me to be perfectly human, with conflicts over loyalty and beliefs and friendship and mentorship and lots of other human feelings. But then, all of that could have been written into the script by the movie people.

On the other hand, I can totally believe your assessment of Eco’s writing as dry, academic and abstract. He was at base a child of the Critical Studies movement and a disciple of deconstructionists like Fourault and Derida. More interesting for me, he was a father in the thinking that became known as the Critical Legal Studies Movement and the Yale School, which morphed into the Critical Legal History Movement, as coined by Robert Gordon at Yale. It is all about power relations in law, and all of my work is about that. Which is why I am a Law and Society Scholar, as are most of the thinkers in the Yale School (as in a school of thought, as opposed to a school as an institution).

Back to Umberto Eco, his work in semiotics was foundational for the Critical Legal Studies Movement, especially the treatment of asymmetrical power relations and the construction of society through language. And yes, it was extremely dry, theoretical, abstract.

Which is why it is weird to this day that he would use that theorist’s brain to write a work of fiction-turned-movie. And I still love that movie.

DCS

And Christian Slater was SO CUTE.

DCS

DCS: I will certainly never forget that first watching of “The Name of the Rose.” It was on HBO, I believe. Or maybe it was a VHS tape.

Please put on our agenda for our next deck discussion the question of asymmetrical power relations, a subject that fascinates me.

Christian Slater was the perfect Adso.

I suspect that one of the reasons the film “The Name of the Rose” was so good was that the cast actually read the book and were smart enough to appreciate it. I similarly suspect that one reason HBO’s “Game of Thrones” is so good is that the cast have actually read the books and know their characters. You can see in the DVD extras that they sit around and actually analyze their characters with great insight, as though they are English majors. Compare the second TV version of Winston Graham’s Poldark. The cast clearly have not read the books and know nothing, nothing, nothing, about their characters. The cast and the screenwriters ruined some of the best historical fiction ever written.

Even when a film version is better than the book — as I believe was the case with “The Name of the Rose” — the screenwriters and cast must nevertheless thoroughly immerse themselves in the book.

All of Gore Vidal’s historical fiction is good, top of my list, I guess because it is peopled by flesh-and-blood humans. Every one of his historical fiction works should be made into movies.

Highly recommended for readers of this blog. Start with “Lincoln: A Novel”:

https://www.amazon.com/Lincoln-American-Chronicle-Gore-Vidal/dp/0375708766/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1506615617&sr=1-1&keywords=gore+vidal+lincoln

Cheers!