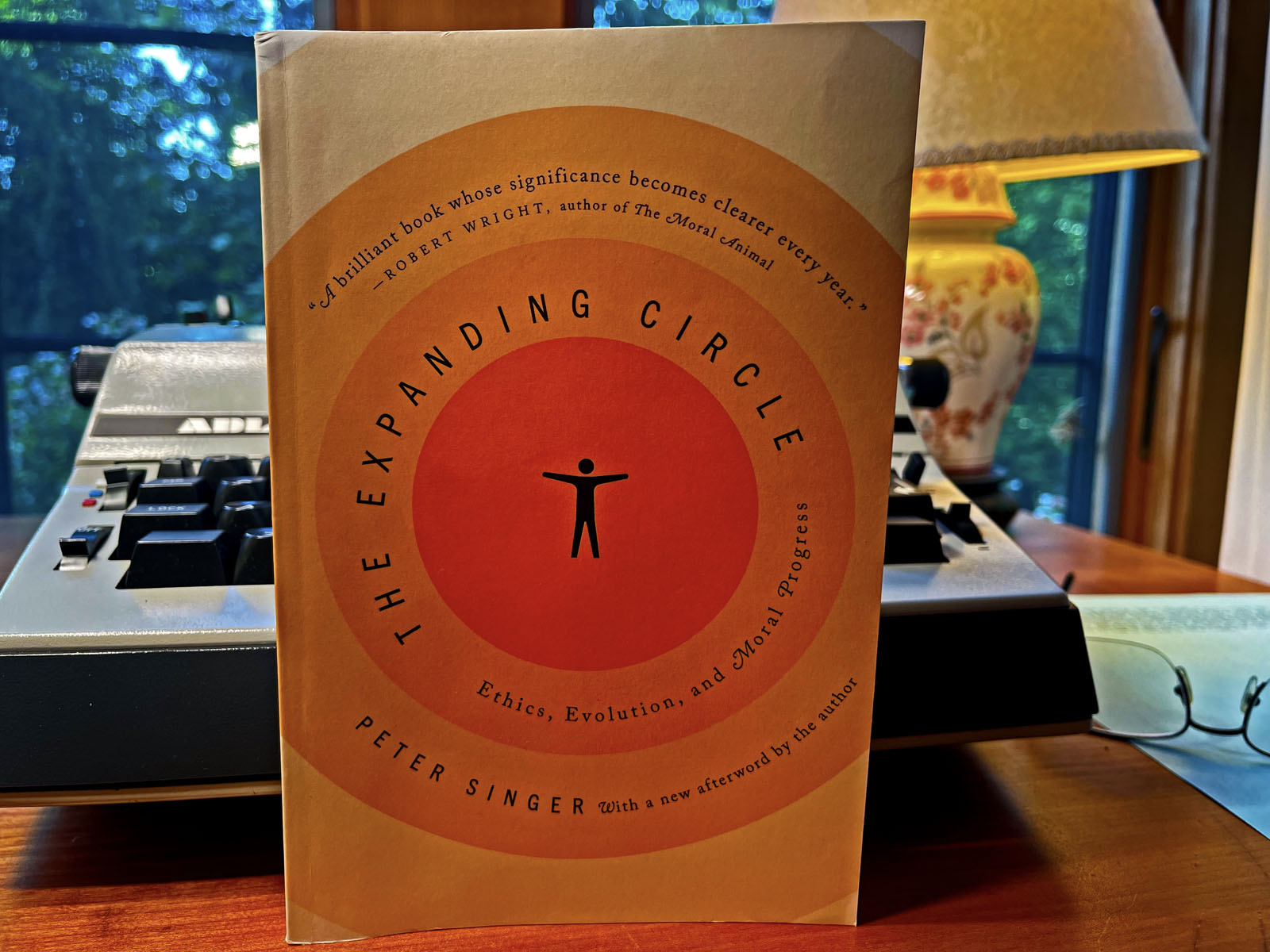

The Expanding Circle: Ethics, Evolution, and Moral Progress. Peter Singer. Princeton University Press. Second edition, 2011; first published 1981. 208 pages.

Peter Singer, born in 1946, is one of our most progressive moral philosophers. In 1975, he published Animal Liberation. For years, he has argued for altruism, from utililitarian principles. In 2015, he published The Most Good You Can Do, which holds that we have a duty to, at the very least, donate money to help alleviate global poverty.

Singer looks largely to David Hume (1711-1776) for the roots of his utilitarian philosophy. Singer’s concern in this book is how it was that moral progress has continued since the time of Hume, as rights were extended to slaves, to women, and even, to a much lesser degree, to animals. Singer calls this the expanding circle. I would call it the arc of justice.

It is reason, Singer believes, that leads to this ever-expanding circle of rights. Applying reason to rights and justice, Singer writes, is like stepping onto an escalator. Once you take the first step, you must ride all the way to the top; there is no way on the way up to get off. There is no reason at all, Singer believes, why animals should not have the same rights as human beings. And Singer is entirely open to the idea, somewhere much higher up on the escalator, that plants have rights, as does the land, a mountain, or a river. On that subject, his sympathy is with Aldo Leopold.

Singer, in this book though, gets into a serious quarrel with the sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson, who died in 2021. Singer entirely accepts Wilson’s case that our “moral intuitions” including altruism have their roots in our human evolution as social animals. But Singer believes that Wilson was entirely wrong in claiming that these moral intuitions are the last word in moral philosophy, with no moral progress possible beyond what is innate in our instincts. We are reasoning beings as well as social beings, Singer argues, and it is reason that leads us up the escalator to an ever-expanding and increasingly altruistic concept of rights and duties.

Singer makes a strong objection to Wilson’s criticism of John Rawls (A Theory of Justice, 1971). Wilson wrote that Rawls’ concept of justice (which is of course based on reason) may be “an ideal state for disembodied spirits,” but is “in no way explanatory or predictive with reference to human beings.” Singer does not discuss Rawls in this book except to defend Rawls against Wilson. But I think it would be safe to assume that Singer has no argument with Rawls. As I’ve mentioned here in the past, Rawls — having stepped onto the escalator of reason — does not attempt in A Theory of Justice to extend to animals his concept of justice as fairness. But as I read Rawls, he almost begs someone else to do that work.1

Why am I so interested in moral philosophy? I would argue that we all should be interested in moral philosophy, as a means of holding our ground and preserving our confidence in an era in which religion and politics increasingly have gone insane, actually belittling the effort toward moral progress as “woke,” using insulting terms such as “social justice warrior.” Religion and right-wingery have always worked to block moral progress. But in the present era they are increasingly open to using violence and corrupting our institutions to gain power and cruelly turn back the clock to a far more primitive time.

Singer paraphrases Leviticus 25:39-46, which I quote here from the Christian Standard translation:

“If your brother among you becomes destitute and sells himself to you, you must not force him to do slave labor. Let him stay with you as a hired worker or temporary resident; he may work for you until the Year of Jubilee. Then he and his children are to be released from you, and he may return to his clan and his ancestral property. They are not to be sold as slaves, because they are my servants that I brought out of the land of Egypt. You are not to rule over them harshly but fear your God. Your male and female slaves are to be from the nations around you; you may purchase male and female slaves. You may also purchase them from the aliens residing with you, or from their families living among you – those born in your land. These may become your property. You may leave them to your sons after you to inherit as property; you can make them slaves for life. But concerning your brothers, the Israelites, you must not rule over one another harshly.”

Though that passage is more than 2,000 years old, it is shocking that, until the Enlightenment, with the church unchallenged, the arc of justice moved so slowly. It was not until 150 years ago that owning and inheriting slaves was outlawed in this country. And now the heirs of the Confederacy2 are reasserting themselves, actually claiming moral superiority for themselves and ridiculing resistance as “woke.”

What does one say to people like that? More important, what does one do to resist them? I return again and again to the words of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was hanged by the Nazis in 1945:

“We are not to simply bandage the wounds of victims beneath the wheels of injustice; we are to drive a spoke into the wheel itself.”

But how?

Notes:

1. John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, p. 448.

2. Heather Cox Richardson, How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America, 2020.

Thank you for posting books like these, David.