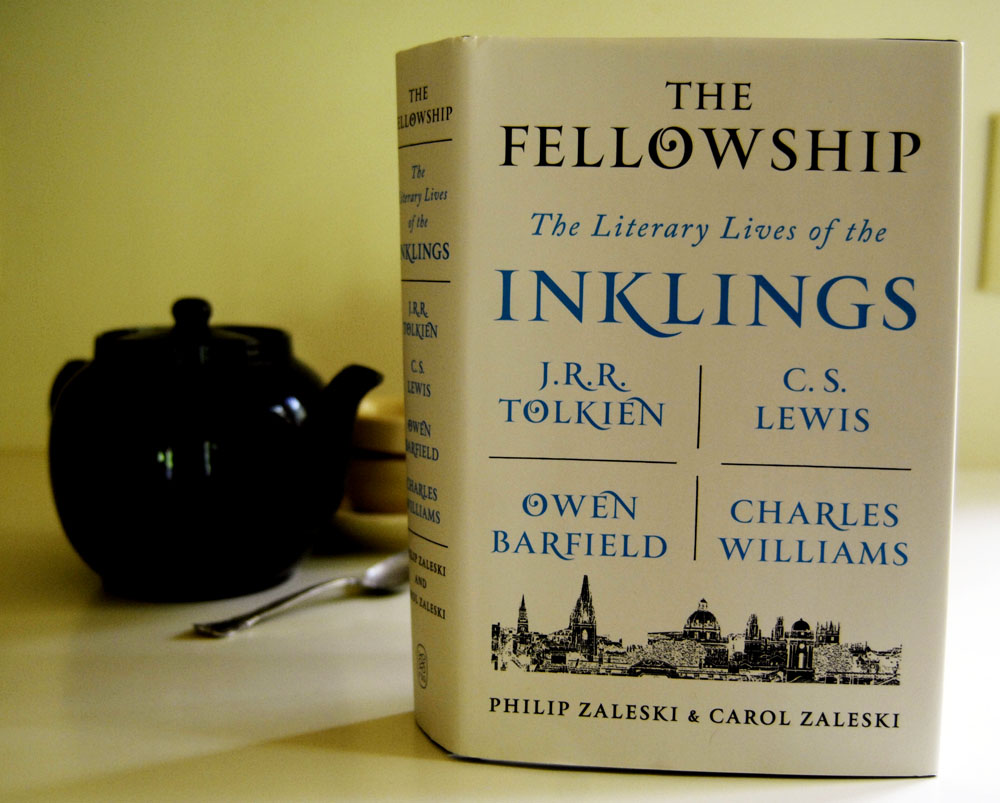

The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings. Philip Zaleski and Carol Zaleski. Published June 2, 2015, by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 656 pages.

I have long been fascinated with how in the world J.R.R. Tolkien managed to produce The Lord of the Rings. A year or so ago, I read his letters. Last June, a new book was released that adds a tremendous amount of scholarship not only to the writing of The Lord of the Rings, but also to Tolkien’s literary group, the Inklings, and to Tolkien’s biography.

This book focuses on four members of the Inklings — J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, and Charles Williams. Barfield and Williams are not nearly as well known as Tolkien and Lewis, of course.

How much fun they all must have had! They met regularly at a pub in Oxford, read from their works in progress, drank, smoked, ate, and butted heads up a storm. Part of the fascination for me is Oxford life. Oxford University has been a center of the intellectual life of the English-speaking people for almost a thousand years. The university press publishes an astonishing 6,000 books a year. And of course in my own post-apocalyptic novels it is Oxford from which the intellocracy is drawn that sets out to remake a post-apocalyptic world.

I have never been able to read C.S. Lewis’ books. My criticisms are much like Tolkien’s (though Tolkien and Lewis got along pretty well most of the time). Lewis’ books are oozing with Christian didacticism and allegory. Lewis was a proselytizer. He was glib. He was argumentative. His personal life was a mess. Though Lewis was not a fundamentalist, there are strong fundamentalist elements of his personality. For much of his life, he was virulently anti-Christian. Then he went through a transformation. As my old friend Jonathan Rauch wrote in one of his first books, Kindly Inquisitors: The New Attacks on Free Thought, fundamentalist personalities have a hard time with gradual, steady, evolutionary personal growth. Rather, they undergo sudden transformations and reversals, rejecting their former selves and heading in a whole different direction. Lewis was like that. To me he was not an interesting person, or an interesting writer.

J.R.R. Tolkien was very different.

It’s important to remember that it has been almost 100 years since Tolkien and other Inklings underwent their formative experiences as young men in the trenches in World War I. The war was an enormous existential challenge to those who lived through it. Then, in middle age, they went through it again with World War II. Oxford at the time was a kind of center of Christianity, a reaction, I believe, to the existential challenges of living in the first half of the 20th Century. They needed a state-of-the-art, Oxford-smart Christianity to make sense of their times.

Not all writers write for the reason Tolkien wrote — to try to find meaning in his life and in the times in which he lived. Tolkien always denied (not least, perhaps, to distance himself from didactic writers like Lewis) that there was anything allegorical in The Lord of the Rings. And yet it’s easy enough to see how his life shaped the story he told — a great struggle by the common folk against a great evil, his hatred for modernity and for machines, his love of untrampled nature, his belief in the power of myth, and his love for the English language.

Though by all accounts Tolkien truly loved ordinary people and loved to talk with them on his long country walks, he was not above calling them “orcs,” when, for example, they cheered for retribution against the Germans. The Inklings were not saints. They argued. They competed for the same academic posts and sometimes went in for a bit of backstabbing. They held grudges at times — sometimes for decades, in Lewis’ case. Lewis’ love life was a disaster (the splendid films “Shadowlands” give a very limited and one-sided view of Lewis and his brother Warnie).

Tolkien, however, comes across as the most likable of the Inklings, the Inkling with the soundest character. And of course it is Tolkien whose literary theory I find most appealing.

I once knew someone who introduced me to C.S. Lewis. This person also went through a radical transformation from a non-Christian lifestyle to one of a fundamentalist Christian, so much of one that he felt he had the authority to tell Christians of other denominations they were worshiping a false prophet. He was successful at burning nearly every bridge he had built as a non-Christian.

He told me first about The Screwtape Letters. I read part of that book and found it dull and overbearing. He encouraged me to read Mere Christianity, and I also read only part of that book. Again, I found it dull. I got the point and agreed with it somewhat, but it still felt like it hinged on the reader’s ability to allow prejudices to decide how they treat others. From there, I read Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not A Christian which sat better with me.

Tolkien is interesting to me not only for his ability to create worlds and languages but because of all things he was, being an anarchist is the most interesting and to many the most surprising. After reading his books, it’s obvious that the hobbits are the only race that have no overt power structure and are the most happy, peaceful, and prosperous. Of course, he doesn’t come out and say that anarchy is the best form of government, and he even crowns a king.

Lewis chose to use his ability to write to spread Christianity, while Tolkien took a more subtle stance and implied that man should be wary of power.

I haven’t read Bertrand Russell’s “Why I am Not a Christian” since the 1980s, and somehow my copy has vanished. I need to get another copy, because I often wish to refer to it.

You bring to mind something we might add to Russell’s list of the moral flaws of Christianity. That is the idea that some sort of instant transformation is possible in the human personality or character, that a person can be “born again” and truly change. On the contrary, people who undergo so-called conversion merely add delusion, hypocrisy and overbearing self-righteousness to their list of character flaws.