I first became aware that the new honeysuckle had arrived when I awoke during the night and caught the scent of it through the bedroom window.

And the grass just gets better and better.

Watching a bewildering world from the middle of nowhere

Grass after today’s downpour: If I’d had it last year I’d have saved some soil and some hard work.

One of the things I’ve learned from building a house is that half the problem, both for the house and the landscaping, is water security. Rain comes in two types, I figure. Just plain rain, which gets to everything that is exposed. And downpours, which can cause heavy runoff and ugly damage.

Here in the South, downpours are common, especially from thunderstorms. Early last summer, almost three inches of rain fell in a violent storm one night before I had established ground cover. The result was ugly and depressing — muddy gullies, parts of the driveway washed out, and young grass washed away before its roots were deep enough to hold on. I’m on a steep hillside. Simply holding the soil has to be my first priority. That’s one of the reasons I’ve not cut my grass. But even when the landscaping is mature enough to not wash out during a downpour, one wants to hold as much water as possible, let it sink into the ground, and either feed the underground aquifer or cause something to grow.

Today just before sunset we had a downpour of between a half an inch and three-quarters of an inch in less than an hour. I did what I always do after a heavy rain. As soon as the rain stopped, I did a walkaround to see how the water was flowing and how things held up. This downpour caused no trouble. No soil washed away. And the tall grass captured a lot of the water so that there really wasn’t much runoff.

Ultimately, with terracing, thick vegetation, and healthy soil, I would like to be able to capture virtually all the water that falls here, with as little runoff as possible. Rain should stay put and make something grow, not run down the hill in a gully.

This bank on the uphill side of my driveway was my most difficult runoff problem. It was nothing but a muddy scar after the driveway was made last spring. Now it’s covered with talls grass and lots of day lilies.

The driveway culvert: running clean and light after a heavy rain

The uphill side of the driveway: not much runoff, even though there’s quite a large watershed above it, and no mud flowing

Of all the billions and billions of pages on lawn care to be found on the Internet, it is exasperatingly difficult to find information on the practical and biological consequences, pro and con, for letting grass go to seed. Apparently there is a small school of thought that it’s beneficial to let grass go to seed once before mowing it for the first time. I have no idea what the reasoning for this is. And then one comes across lawn “experts” who deliver severe scoldings to anyone who would consider letting their grass go to seed before mowing it. One of these experts did at least make reference to some rational reasons — is the grass a hybrid and will the seeds be “true,” how the grass deploys its energy to different parts of the plant, etc., etc.

I have seeded my acre of sun again and again since the pine trees were taken down in March of 2008. I’ve used a lot of Kentucky-31 tall fescue, simply because this is the cheapest grass seed, it’s available everywhere, and it’s well adapted to this area. But I’ve also made an effort to work in other types of more expensive fescues, with the hope that whichever type of grass was best suited to a particular area would dominate in that area.

Is Kentucky-31 a hybrid? It’s amazing how hard it is to find that information, but my guess is that it is not a hybrid and that the seed it produces will be true Kentucky-31. But what about the other fescues I planted? Were they hybrids? Who knows.

In any case, what if I do have some hybrids, and their seed yields poor quality grass? I think the answer is, who cares? Because the grass from better seed will dominate over time.

One of the arguments for gardening with heirloom vegetable seed is that, over time, as one selects the best specimens of vegetables for seed-saving, your vegetables adapt themselves to your garden.

I can’t think of any reason why the same should not be true for grass. If one starts with a mix of fescues and lets it go to seed again and again, then eventually one’s grass will adapt itself to the land on which it’s growing.

After all, that’s the story of how Kentucky-31 — festuca arundinacea — was discovered in the first place. A professor of agronomy from the University of Kentucky had heard of a “miracle grass” growing on a hillside in Menifee County, Kentucky. This miracle grass was thriving during a drought. That was 1931, hence the name Kentucky-31.

Horrors. Someone let some grass go to seed on a hillside. And it adapted. What lazy lawnmower-hating slacker let that happen?

I guess I’ll just have to run my own experiments with letting grass go to seed. Yes, it starts to fall over when it gets tall. But, growing at the base of the clump of tall stems there always is a clump of new, short stems ready to take their place.

I have lots of questions. How does tall grass handle dry weather? Does tall grass require net more or net less water? I suspect tall grass may conserve water, because it shades the soil, and mowing grass apparently makes grass very thirsty until it recovers from the mowing. Will tall grass smother out clover and wildflowers? Maybe that’s why so many wildflowers have tall stems. I’ll report on my experiments periodically.

One thing though, is already very clear, and it’s in accord with what the “lawn experts” say. I was unable to establish grass in the spring of 2008. The grass was not able to develop a root system before the summer heat scorched it. The only stuff I had growing in the summer of 2008 were the hardy, native species that volunteered. However, the grass I planted in September of 2008 took off like crazy. It now has thick, deep roots. So it certainly seems to be true that, when starting fescue from seed, you get much better results in the fall.

See the follow-up to this post from eight years later: On letting grass go to see (follow-up)

A green exuberance returns to the area around the house which a year ago was bare after the elderly pine trees were removed.

The chickens are growing a new set of feathers and look pretty ratty at the moment.

Purslane, to be eaten for its omega-3

A deciduous magnolia in a sea of fescue. At the bottom of the sea of fescue is a layer of clover.

A day lily strains to get its head above a sea of fescue.

Catnip, which grew from last year’s roots

A baby apple tree inside its deer cage

A day lily, which somehow survived the ditch witch when the water pipe was buried

The chickens pose for a picture shortly after moving into their new house, before they had a chance to dirty it up.

The chickens moved into their new house today. They’re now 12 days old. They’ve spent the last week living in a box upstairs in my unfinished house, where they got in the way of all the work that was going on this week. Now that they’re older and the weather is a bit warmer, I’ve moved them into their new chicken house. They still have their heat lamp for cold nights.

My brother built the chicken house. We considered a number of designs for backyard chickenhouses, but we liked the house-on-stilts design the best. It affords some extra protection from predators and easier access for human caretakers. There’s a screen around the bottom, and a door in the floor of the chicken house. There will be ramp stairs between the two levels soon.

I’m still thinking about security from predators. I may put a run of electric-fence wire around the base of the chicken house and have a timer turn it on from dusk until dawn.

The plywood panel in the front is temporary, covering the spot where the nests will be. The nests will extend out from the front of the chicken house, with egg-robbing doors on the outside.

The sounds that go with this: the quiet sound of falling rain, a distant dove, a bird chirping in the woods

Right now I hear: The sound of a light rain pattering on the roof of the travel trailer, and a dove calling in the distance. That’s it.

When I first moved to San Francisco in 1991, I don’t recall being particularly offended by the noise. By the time I left in 2008, the noise was driving me crazy. I’m not sure why. It may be that the aging ear, more and more, resents noise and the work of filtering signal from noise. Or maybe it’s that I already was so stressed that the noise was a greater aggravation. If I were in San Francisco right now, I’d hear: Buses, trucks, and motorcycles roaring up the hill around Buena Vista Park, and sirens, sometimes close and sometimes distant, almost non-stop. In my last year in San Francisco I sometimes wore noise-canceling headphones to diminish the noise. Walking down Market Street is almost unbearable. The noise level is so high that it’s almost impossible to even carry on a conversation with someone walking beside you.

Silence is priceless. Sometimes I think that the money I’ve spent here is worth it only for the silence I now live in.

Living alone in a quiet place, one realizes that the sounds we hear carry far more information than we may realize at first. I’ve been reading up a bit on the science of acoustics to try to better understand the propagation of sound. Why, for example, on a quiet night in a rural area, do we hear trucks on a distant highway, but other times we don’t?

The key factors that affect the propagation of sound are the frequency of the sound, the relative humidity, and the temperature. Lower-pitched sounds travel farther and get around obstacles better than high-pitched sounds. Higher relative humidity allows sounds to travel farther. Lower temperatures allow sounds to travel farther. So, on a cool, humid night we are more likely to hear the low rumbling sound of trucks on a distant highway. The sound of a foghorn, fortunately and unsurprisingly, travels farther in the very conditions that create the fog.

A sound that comes from higher up travels farther than a sound that comes from closer to the ground. A singing bird can make itself heard twice as far by singing from a higher perch in the tree.

Scientists who study the communication of birds also study the acoustic properties of the soundscapes or auditoriums in which birds are heard. The book Nature’s Music: The Science of Birdsong, can be previewed at books.google.com. It contains an excellent technical discussion of how soundscapes affect the propagation of birdsong.

Few sounds travel farther than thunder. Its pitch is low, it originates high up, and it’s often accompanied by high humidity and cooler air. Last summer I often sat out on the deck as a storm approached just to enjoy the sound of distant thunder. I soon realized that I wasn’t hearing just thunder. I was hearing the local terrain. Because the sound of thunder easily travels for five miles or more, when listening to thunder one’s auditorium has a diameter of 10 miles or more, and one can hear the presence of hills and valleys within this large auditorium, just as you hear the presence of a nearby wall if your eyes are closed. If you listened carefully enough and long enough, I believe you probably would be able to say, “I hear a high hill about four miles to the north, and there is what sounds like a river valley to the south.” I have little doubt that our ancestors understood intuitively how to do this.

It’s not a random thing that I’m writing about this subject now. It’s because my ears, now attuned to silence and the sound of nature, have clearly detected a change of season. Even if I had not seen a robin, I’d know the birds are back. I’m hearing familiar voices in the woods that I have not heard in months. Also, the woods are a very acoustically live auditorium at present. There are no leaves on the trees, so the woods reverberate like a very large room. When the trees have leaves, the level of sound from the woods, and the reverberation, will be greatly attenuated.

But even as the woods become muffled by leaves, my auditorium will extend across the hollow, where there are few trees, to the next ridge. When the wild geese fly over, I hear them honking as soon as they cross the ridge into the hollow, my auditorium. And though I heard a pack of coyotes in the woods during the winter, I probably would not hear them when the trees have leaves, because the leaves attenuate the sound so quickly, and the shrill voices of the coyotes are high pitched.

All of the factors that separate us from these nature sounds are forms of pollution. It is as though we live at the bottom of a filthy lake of sound pollution and light pollution. I never realized until I was reading up on natural acoustics that noise pollution reduces bird populations. That makes perfectly good sense, because birdsong is a form of communication, and birds don’t want to live in places where noise prevents them from getting (and sending) information about their environment. Even here in the foothills, trucks, and to a much greater degree, airplanes, pour a huge amount of filth into the natural soundscape.

It is clear to me that I could never tolerate living in a noisy place again.

It has been an uncommonly cold winter, with an overall low of 2.3F, plus many nights with a low below 15F. There also was too little rain this winter. A nice spring rain fell today, and the temperature reached 55, but more cold weather lies ahead, with forecast highs for the next four days of 46, 38, 38, and 45. So it’s not exactly looking like spring.

However, I’m expecting the rain to jump-start the young grass and clover. My daffodils, I’m afraid, are still two weeks or more away. I wish my garden would plant itself, because I’m very busy with the house.

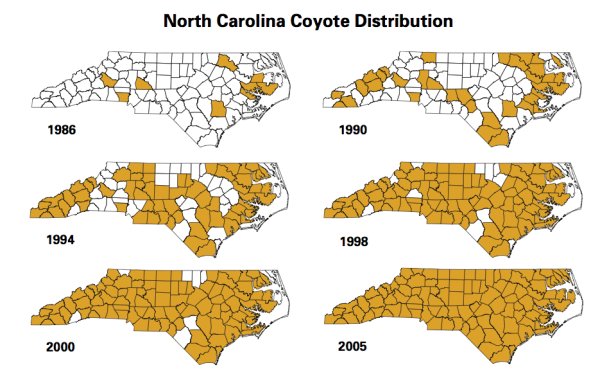

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

The cat woke up and make quite a fuss about 3 a.m. when she heard a pack of coyotes in the woods. It’s the first time I’ve heard coyotes in North Carolina. I’ve heard them before while camping in the mountains of California, near Yosemite. It’s a primitive sound — a spooky choir of high pitch yelps that sound as though they have to do with the final frenzy of hunting.

There’s a lot of lore and misinformation about coyotes in North Carolina, but I believe this article from the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission tells the story. Coyotes, it seems, have extended their range into North Carolina over the past couple of decades, and they’re here to stay.