Click here for high-resolution version.

I seem to have become a collector of vintage Harris tweed jackets, after a visit to the Isle of Harris and Lewis in 2019. That’s a slippery slope, because, before long, the tweed habit leads to Donegal tweed as well.

Much has been written about Harris tweed. Less has been written about Donegal tweed. As far as I can tell from Googling, it was Harris tweed that came first and led the way. According to an article in Gentleman’s Journal: “Although the story of tweed began in Scotland, it quickly migrated to Ireland where, in 1900, Robert Temple bought off John Magee’s business and started weaving the illustrious Donegal tweed.” More about Magee in a moment.

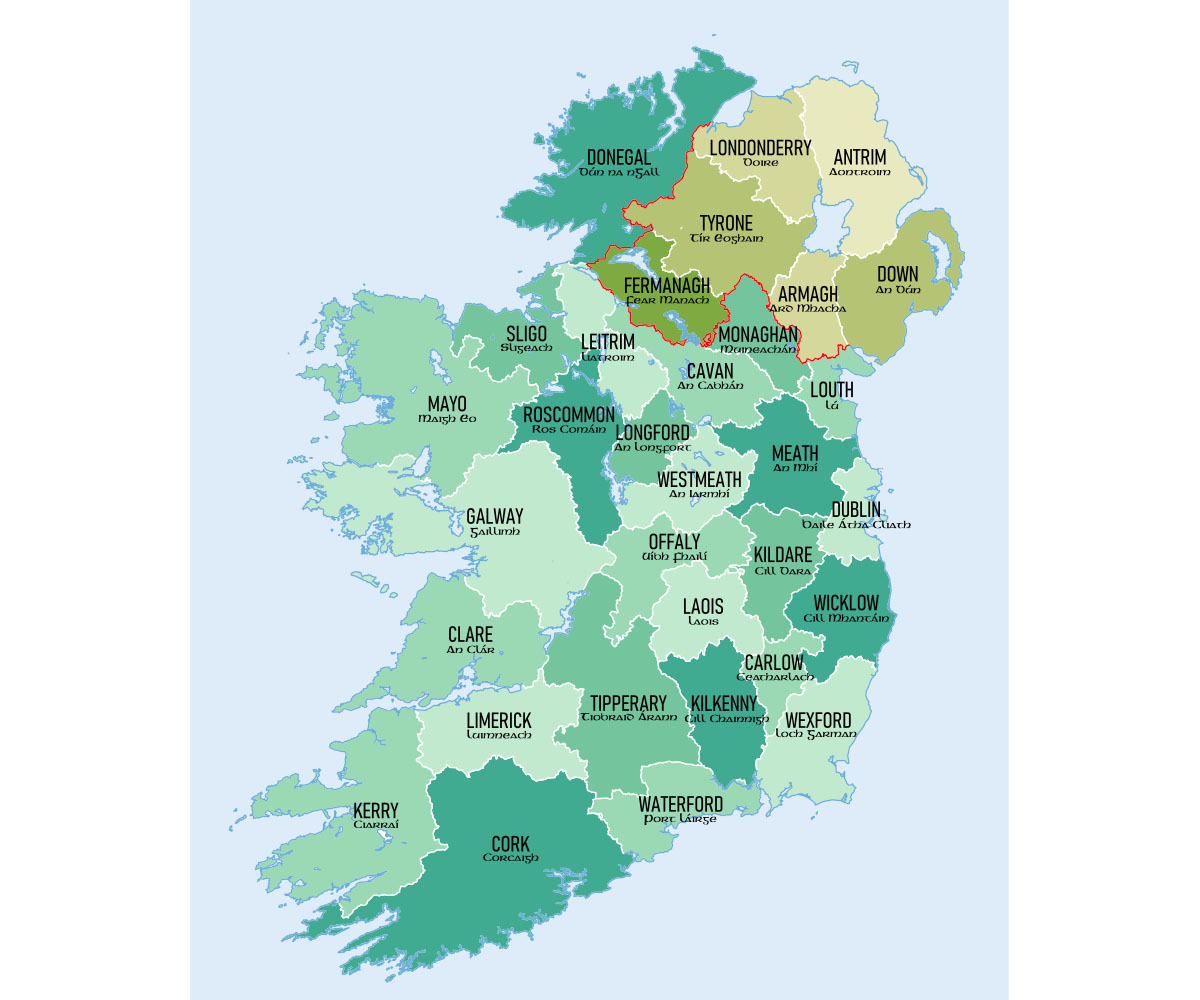

County Donegal and Scotland’s Isle of Lewis and Harris have a lot in common. They both have rugged western coasts facing the North Atlantic. Though I have not been as far north in Ireland as County Donegal, the terrain, climate, and economic potentials are very similar — sheep-friendly, and a sparse population of cottagers in need of work and an income. What worked economically for the Isle of Harris also worked for County Donegal.

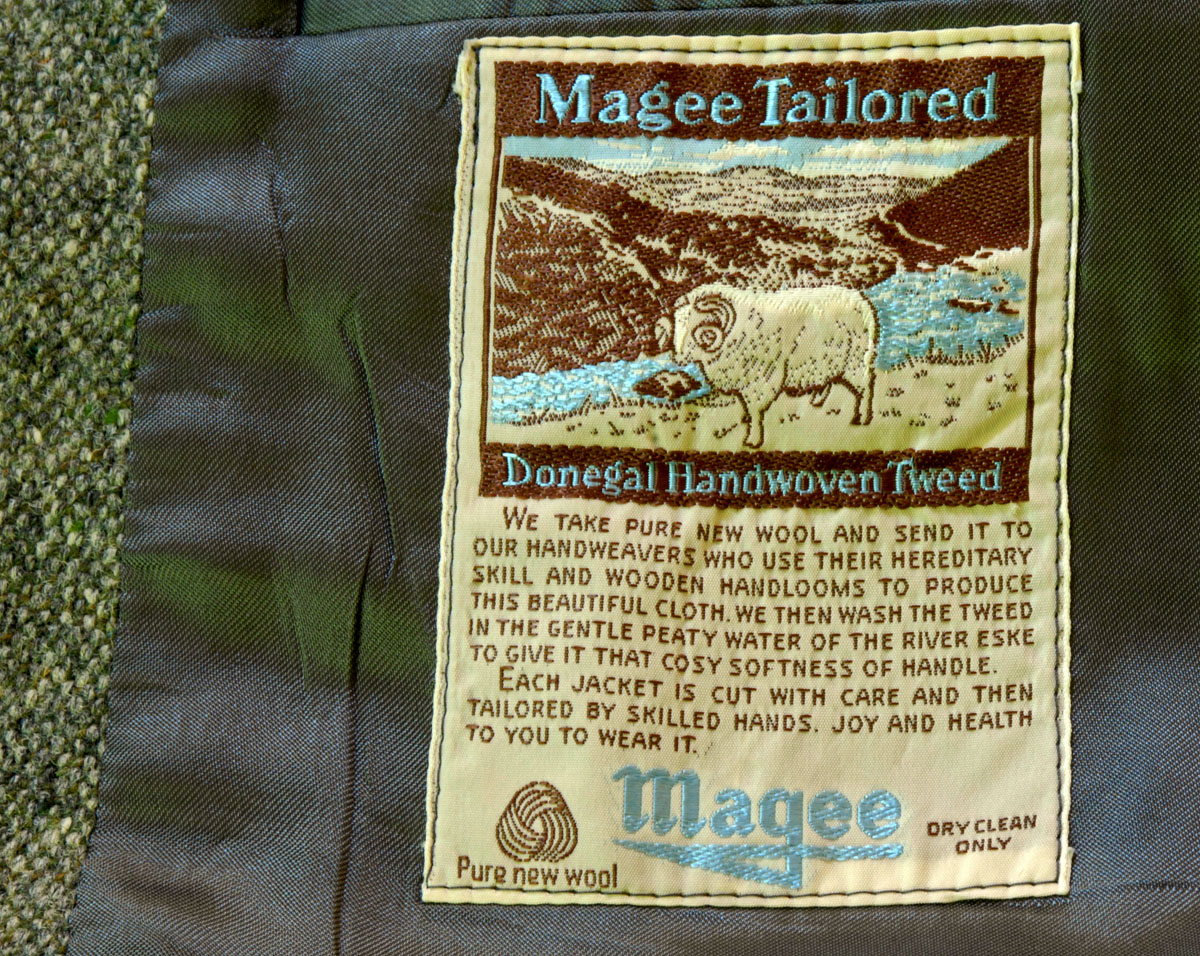

My understanding is that, by law, Harris tweed is produced only on hand-operated looms. The label on my 1970s Magee jacket says that the tweed was handwoven. I don’t disbelieve that, though this article says that the production of Donegal tweed today is dominated by power looms. The Magee company acknowledges the use of power looms in this article on their web site. The article also says that they continue to produce handwoven tweed, though when I spot-checked fabric and clothing for sale on their web site, the descriptions said, “All tweeds are woven in our mill in Donegal, Ireland.”

In any case, a single company — Magee — seems to have dominated the Donegal tweed business since the beginning. They are still very much in business today. Men’s jackets seem to average around $600. They have stores in Donegal and Dublin, and they ship to the U.S.

It’s very unlikely that I would ever buy a tweed garment new. What would be the sport in that? As I mentioned in a post here on Harris tweed last year, there is a good market on eBay for vintage tweed clothing. Sellers are usually very good at providing the information buyers need to judge a men’s jacket. Usually there will be 10 to 12 photos from multiple angles. If there are flaws such as rips, there will be a photo of it. Best of all, they provide measurements that I have found to be accurate. Jackets in great condition can be had for $40 up. Typically I pay $60 to $100. The cost of alterations may add another $100, so a nice jacket ends up costing less than $200. Tweed just doesn’t seem to wear out. A jacket’s lining will be the best indicator of how much it has been worn. I always look for jackets with like-new lining.

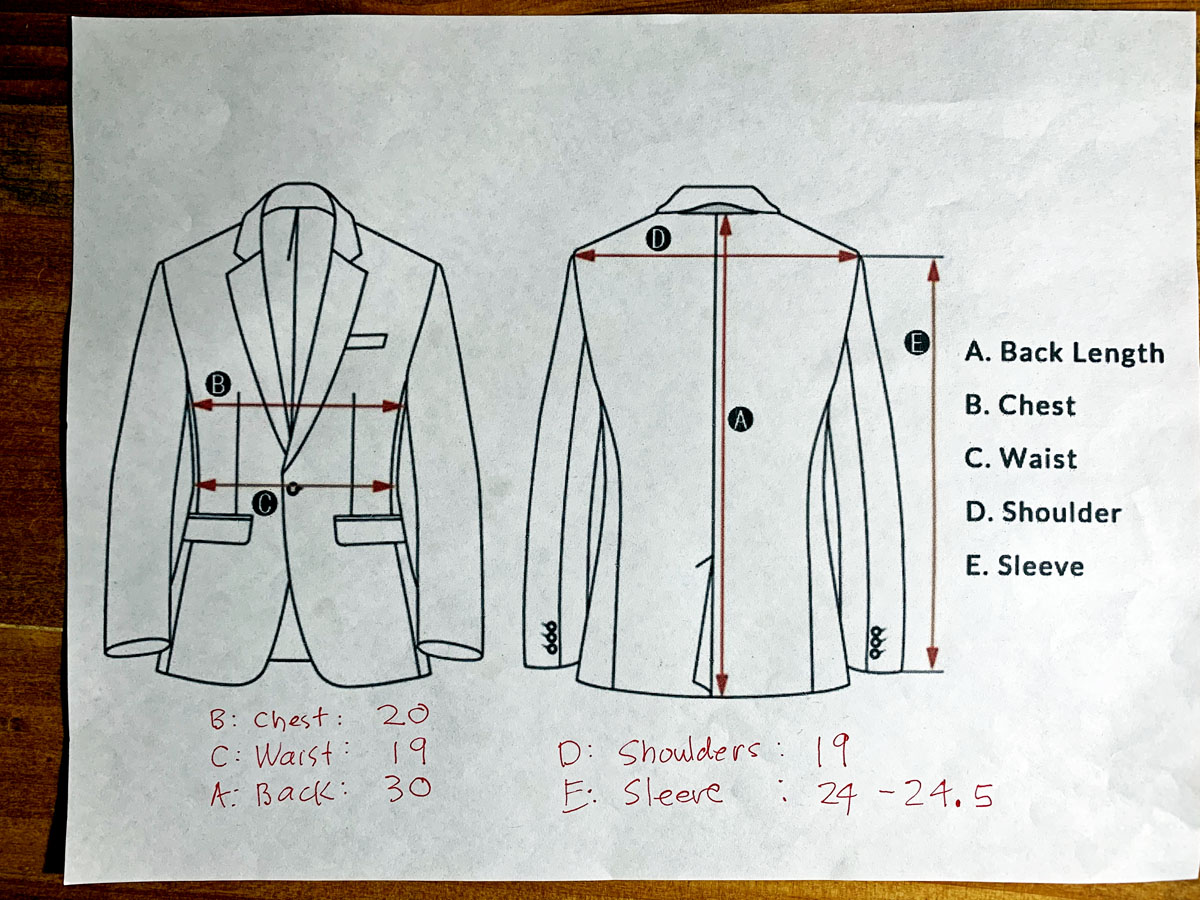

My article on Harris tweed has gotten quite a few hits from Google, mostly from readers in Europe. There seems to be a growing interest in vintage tweed, at least in men’s jackets. For those who are interested in collecting, I’d make two suggestions. First, you need access to a tailor or someone with tailoring experience who can do a proper job of alterations. And second, you should keep your own measurements handy when looking at jackets. eBay sellers will typically lay a jacket flat and use a tape measure. You should do the same to get your own measurements, using a jacket that fits you well. It’s the same as buying clothing off the rack (the only kind of clothing I’ve ever owned). Some alterations are easy; some are difficult or impossible. Don’t buy a jacket unless the shoulders are just right, because shoulder alterations are not worth what they’d cost, even if it can be done at all. Letting out or taking up sleeves is no big deal. But if sleeves need lengthening, you’ll need to know how much fabric there is in the sleeves that can be let out. No jacket will look good on you unless the chest and waist fit well. Tightening the waist and chest of a jacket are not a big deal, but there will be limits on how much letting out can be done, depending on how much fabric is available to do it.

I’m trying to honor a new rule to try to keep my collector habit under control. That’s to buy only jackets that are of high quality and in great condition, to buy only great bargains, and to try to buy only jackets that need no alterations. The jacket in the photo, for example, fits great without any alterations, though I plan to move the buttons about 3/4 inch to slightly tighten up the waist.

County Donegal, by the way, is part of the Republic of Ireland, to the west of Northern Ireland. I have never been north of Dublin, and I have never been to Northern Ireland. I certainly hope to get to Donegal someday.

My post on Harris tweed from August 2019.

This jacket was quite a find — made by Magee in County Donegal, from handwoven tweed, from an American seller, and little or no alteration needed. I would guess that this jacket was made in the late 1970s.

The measurements I use when browsing for collectibles on eBay.