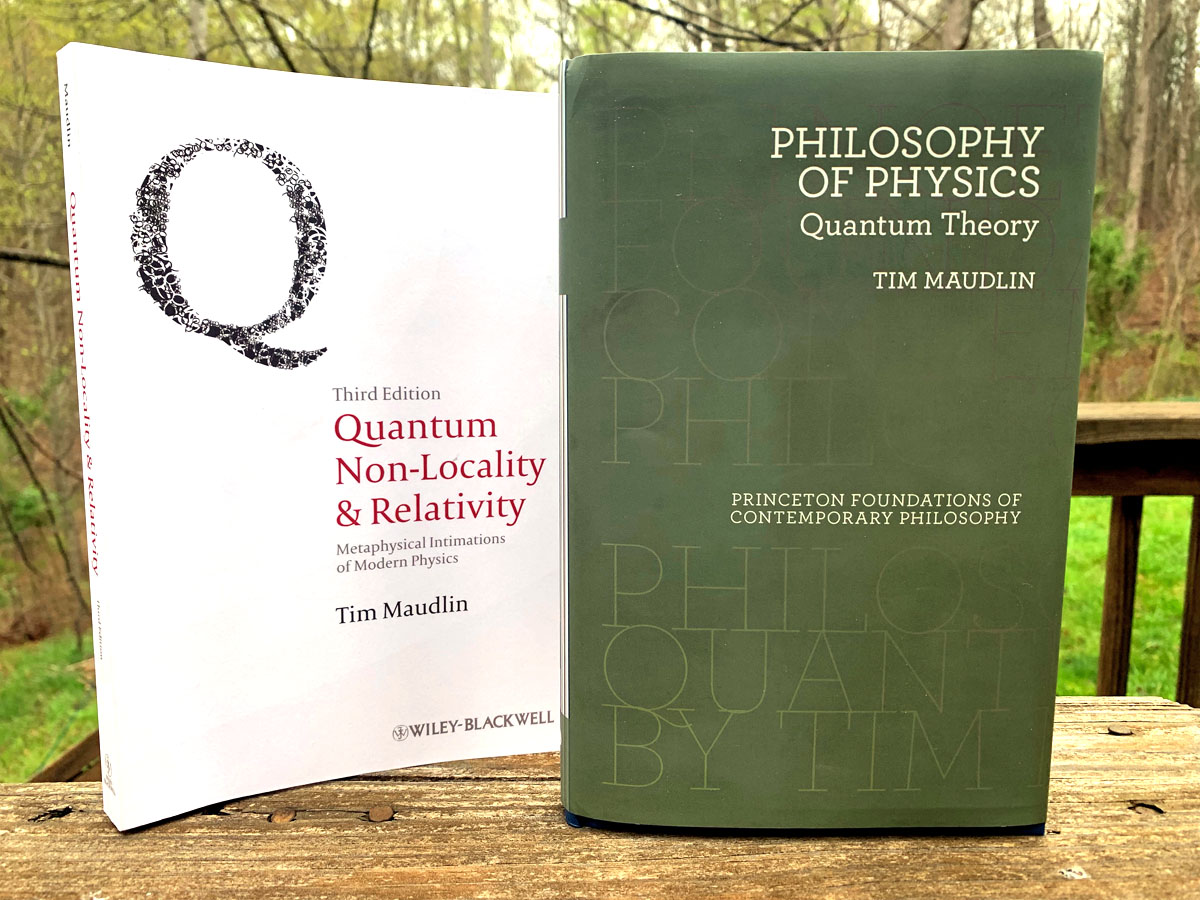

Philosophy of Physics: Quantum Theory, by Tim Maudlin. Princeton University Press, 2019. 234 pages.

Quantum Non-Locality and Relativity: Metaphysical Intimations of Modern Physics (third edition), by Tim Maudlin. Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. 298 pages.

John Twelve Hawks was clearly troubled, and I don’t blame him. (John Twelve Hawks is one of my favorite science fiction writers. I’ve written about him here several times and reviewed his books. Just search here for “twelve.”) I follow John Twelve Hawks on Facebook. He had posted a link to an article in the MIT Technology Review. The terrifying headline on the article is: A quantum experiment suggests there’s no such thing as objective reality. He made this comment about the article:

“Some philosophers are drawn to the the idea that humans are organic robots that make decisions determined by our own biology and environment. I think these ideas let us off the hook for the real choices we can make in our lives. A variety of experiments have shown that people who think they aren’t free feel that it’s okay to hurt another person. ‘Un-freedom’ becomes an alibi. So my day-to-day assumption is that objective reality might not exist, but assuming that it is encourages us to live responsible, compassionate lives. Please feel free to tell me that I’m wrong!”

Actually, academic philosophy has a word for humans as organic robots. That word is zombie. You can read the article on zombies here in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The zombie concept (as much as I detest zombie movies) is a useful concept in thinking about what it means to be a conscious, not to mention a decent, human being. If we are not zombies, then what is it in us that makes us something else?

It happened that I had just finished laboring my way through these two books when I came across John Twelve Hawks’ comment. I cannot follow most of the math of relativity and quantum theory. But I do think that I have a tenuous grasp of the gist of it. I have read a lot of books like this, and I imagine that John Twelve Hawks has, too (as would any science fiction writer who is worth the ink). If John Twelve Hawks was troubled by the suggestion that there is no such thing as objective reality, I was horrified. We are living in an era in which many people feel that they are entitled to their own facts and their own reality. Do we really need to embolden fools with the notion that cutting-edge physics is on their side?

Tim Maudlin probably is the leading philosopher of physics. Quantum Non-Locality and Relativity is a standard textbook in this area. I knew that Maudlin would rip to shreds the idea that objective reality might not exist. I worried that, if Maudlin even bothered to respond to the piece in MIT Technology Review that it might be a long time before he got around to it. But I was wrong, because (as I discovered from Googling) Maudlin was all over it immediately. The Daily Nous is a place where academic philosophers hang out on line. Several philosophers of physics wrote responses, including Maudlin. Here is a link to Maudlin’s response, which has the headline If There Is No Objective Physical World Then There Is No Subject Matter For Physics. Here’s the money quote: “Objective reality is safe and sound. We can all sleep well.”

On what grounds does Tim Maudlin say that objective reality is safe and sound? To answer that question, you’ve got a lot of reading ahead of you. Modern physics is so strange that many physicists actually believe that all possible futures are real, and that a whole new and slightly different universe is created every time some tiny particle undergoes “quantum decoherence.” This is called the Many Worlds Interpretation. Maudlin thinks that’s bunk. For what it’s worth, I do, too. I would say that the reason the minds of many physicists are drawn to the Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI) is that MWI returns physics to a kind of determinism. The alternative to determinism is spooky, and they don’t like spooks. It was Einstein, I think, who first used the phrase “spooky action at a distance.” For what it’s worth, I like the idea of a spooky universe.

I am by no means qualified to actually review these books. But I do want to argue that, when these mysteries in physics are eventually resolved, it will be the most important new knowledge in our lifetime (if we are lucky and it happens in our lifetime).

If Quantum Non-Locality and Relativity could be boiled down to one key point, I would say that it’s this: Spooky action at a distance is real. Get over it.

Philosophy of Physics: Quantum Theory is a survey of current candidates for a grand unification theory that can reconcile the contradictions between relativity theory and quantum theory. We seem to not be getting any closer, really. (And I’m not getting any younger.) These theories are largely incompatible. Physicists and philosophers of physics are polite to each other in their books. But online they can be a bit snarky about theories they disagree with.

But you don’t have to be a physicist or a philosopher of physics to choose sides and root for the spooks. You could even come up with your own theory, though you’d have to provide the math to support it.

I confess I have a sneaky suspicion about where it’s all going. I like to play with the idea that there is nothing here. Maudlin actually comes very close to the temptation of that idea himself, in the conclusion of Philosophy of Physics: Quantum Theory (page 221):

“This possibility makes it tempting to deny the existence of any fundamental particles at all. If particles exist, the thought goes, there must at any given time be a definite, exact number of them determined by the number of distinct trajectories. But in a state of ‘indefinite particle number,’ no such exact number exists, so there can’t be any particles at all. Instead there is a field that can, in particular circumstances, act in a more-or-less particle-like way.”

That there is nothing here is by no means a new idea. In Eastern philosophy, as John Twelve Hawks would know, it is called maya, a kind of light-and-magic show. But that cannot mean that anything goes. Yes, the spookiness seems to be real. But nevertheless the universe remains strictly governed by its mathematics. Much of that math physicists already know. But the biggest piece remains elusive. As for maya, I am not very interested in what ancient philosophy says on the matter. They didn’t provide any supporting math. I only want to know what physicists ultimately figure out.