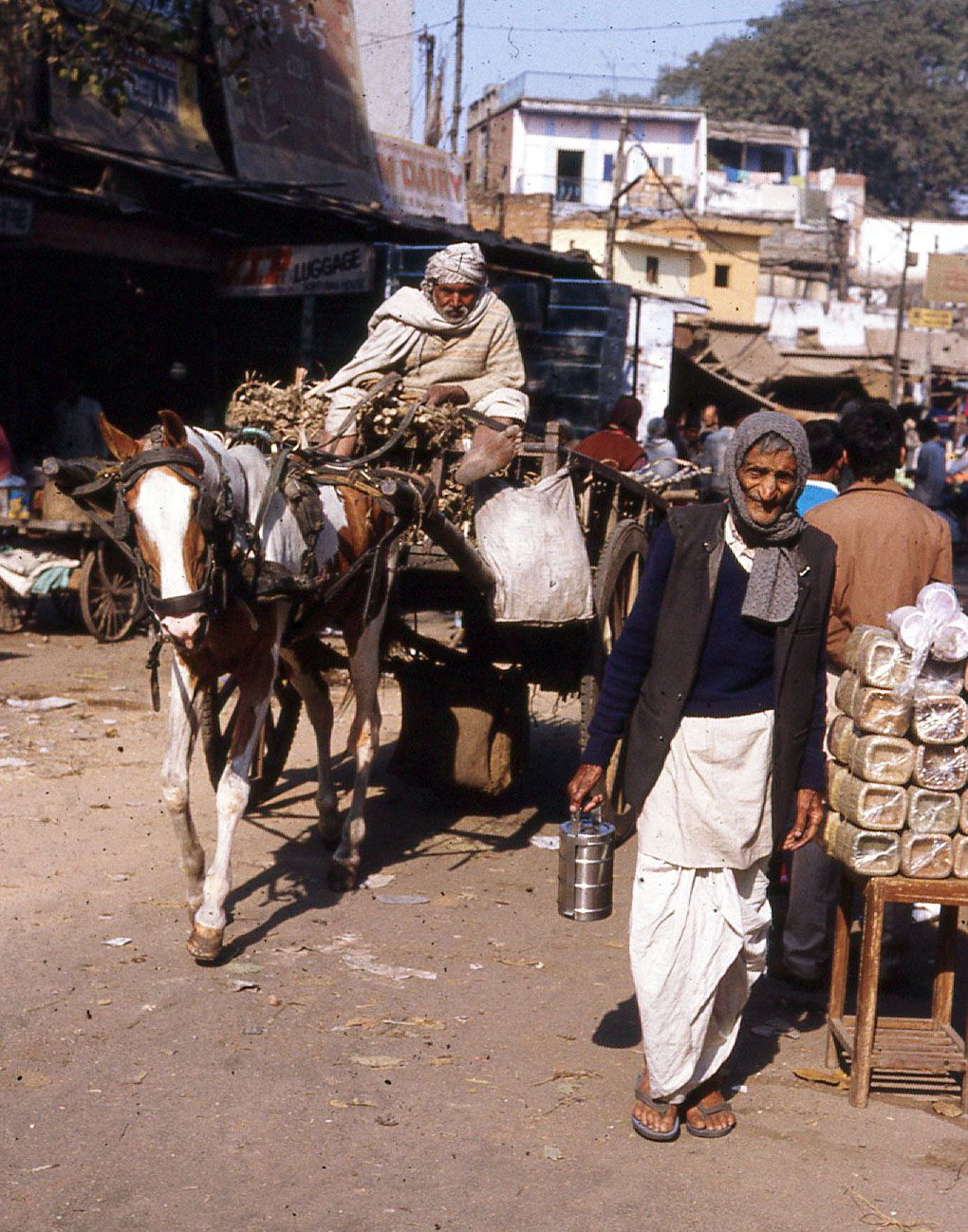

Amazon’s new automated store in Seattle. Source: Wikipedia

Trump voters and consumers of Fox News are having the time of their lives these days, glorying in how their big man is sticking it to liberals, immigrants, and brown-skinned people. They actually feel safer, now that a con man is in the White House who feeds them what they want to hear.

Meanwhile, their world is about to go even deeper down the rat hole. The right-wing media will see to it that they won’t know what hit them.

For decades now, the 1 percent have been raking in most of the gains, while working people’s share of wealth and income shrink. Working people really don’t understand just how rich the global rich really are. Still, inequality has reached politically dangerous levels. The rich know that the political danger is rising, but so far the rich have been successful at using their media and their political control to misdirect the growing economic discontent. The rich would much rather have fascism in America than European-style democratic socialism. The Trump era, with its demonization of government, its propagandization of the population, and its packaging of the rich people’s agenda as heartland populism, reveals to us how the rich intend to keep their gains and keep on bamboozling the losers.

Meanwhile, the liberal media are trying to warn us that a new wave of economic upward redistribution is about to hit working people: robots. In the New Yorker, we have “Amazon’s New Supermarket Could Be Grim News for Human Workers.” The Guardian writes: “Robots will take our jobs. We’d better plan now, before it’s too late.” Even a business-oriented industry publication writes: “From robots to smart mirrors, the world of retail will look like a very different place in 2030.”

While robots take jobs from humans at an accelerating pace, the intent of the Republican Party is to go right on cutting the safety net for working people, while cutting taxes on the rich and shifting taxes to lower-income people.

Republicans can’t say they weren’t warned. Policy think tanks such as the Brookings Institution have published report after report about where inequality is leading and how inequality endangers democracy. But Republicans don’t care about policy (or democracy) anymore. The Republican project is simply to enact the rich people agenda.

With the right kind of enlightened public policy, this country might be able to survive the coming wave of jobs lost to robots. But I have no hope of that ever happening unless justice catches up with Donald Trump and a whole lot of Republicans go to prison for their crimes. We’re still seeing only the shark’s fin above the surface of the water, but leak by leak it’s becoming pretty clear who those criminals are. The guilty are using increasingly dangerous and desperate tactics to evade justice. What blows my mind is that about 35 percent of the American population — economic losers, almost all of them — feel safer than ever during one of the most dangerous times in American history.