For at least 200 years, the Druids have been hopelessly romanticized. The Druids, of course, were the highest caste of the Celts. With the exception of making war (from which Druids were exempt), the Druids performed the leadership functions of the Celts — priests, judges, scientists, and philosophers. Maddeningly little is known about them. Many works of imagination have been written about the Druids, but hard, well-sourced information is very, very scarce.

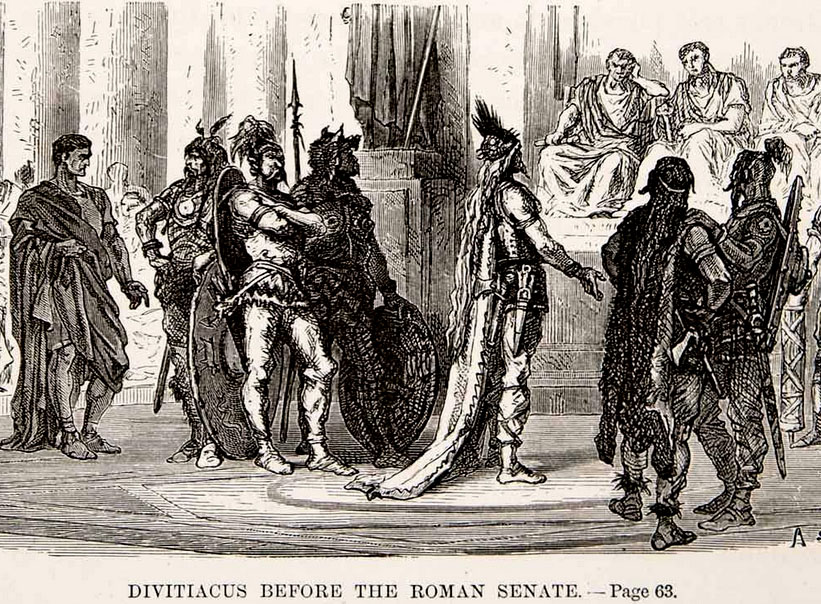

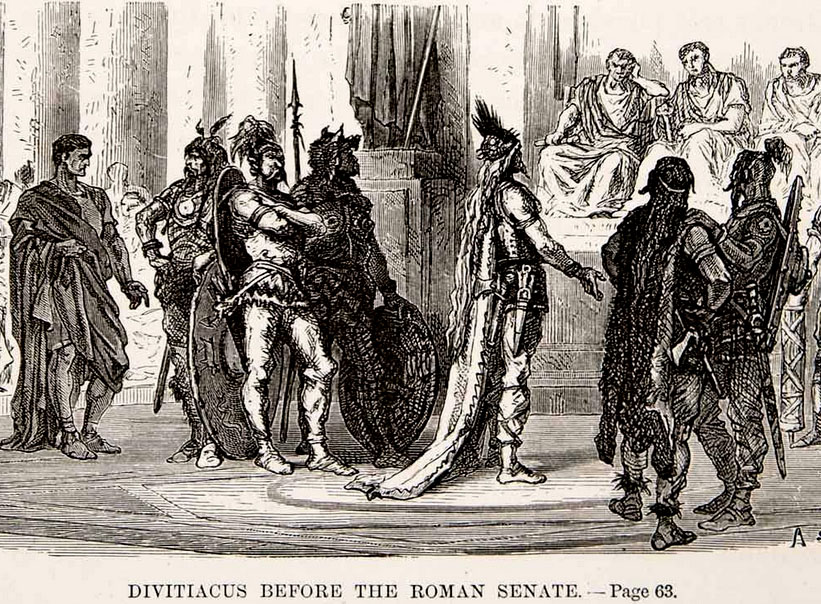

Greek and Roman historians mentioned the Druids, but I believe that only one Druid is known to history by name. That was Divitiacus, a Druid of the Aedui nation, which lay between Lyon and Dijon in what is now France, near the border with Switzerland. Divitiacus’ nation, the Aedui, had been badly defeated by a rival tribe allied with Germans. Divitiacus went to Rome and pleaded before the Roman senate for help.

While in Rome, Divitiacus stayed with Cicero. Cicero mentions Divitiacus in his Divinations. Cicero spoke highly of Divitiacus, who was treated like a king in Rome. Divitiacus, said Cicero, would predict the future, “either by augury or his own conjecture.”

Julius Caesar makes many mentions of Divitiacus in The Gallic War, in books 1, 2, 6, and 7. Caesar trusted Divitiacus and greatly respected him. Caesar even went easy on Divitiacus’ rebellious brother, Dumnorix, out of regard for Divitiacus.

Druids are usually romanticized as old people in robes. But Divitiacus was quite young. He was believed to be about 32 when his nation was defeated by the rival Sequani and the Germans, and he probably was 35 or 36 when Caesar knew him. Caesar knew Divitiacus in Divitiacus’ role as a diplomat and leader of his people.

Caesar has a little to say about the Druids in The Gallic War:

“[The Druids] are concerned with divine worship, the due performance of sacrifices, public and private, and the interpretation of ritual questions. A great number of young men gather about them for the sake of instruction and hold them in great honour. In fact, it is they who decide in almost all disputes, public and private; and if any crime has been committed, or murder done, or there is any dispute about succession or boundaries, they also decide it, determining rewards and penalties. If any person or people does not abide by their decision, they ban such from sacrifice, which is their heaviest penalty. Those that are thus banned are reckoned as impious and criminal. … Of all these Druids one is chief, who has the highest authority among them. At his death, either any other that is preeminent in position succeeds, or, if there be several of equal standing, they strive for the primacy by the vote of the Druids, or sometimes even with armed force. These Druids, at a certain time of the year, meet within the borders of the Carnutes, whose territory is reckoned as the center of Gaul, and sit in conclave in a consecrated spot. Thither assemble from every side all that have disputes, and they obey the decisions and judgments of the Druids. It is believed that their rule of life was discovered in Britain and transferred thence to Gaul. And today those who would study the subject more accurately journey, as a rule, to Britain to learn it.

“The Druids usually hold aloof from war, and do not pay war-taxes with the rest. They are excused from military service and exempt from all liabilities. Tempted by these great rewards, many young men assemble of their own motion to receive their training. Many are sent by parents and relatives. Report says that in the schools of the Druids, they learn by heart a great number of verses, and therefore some persons remain twenty years under training. And they do not think it proper to commit these utterances to writing, although in almost all other matters, and in their public and private accounts, they make use of Greek letters. I believe they have adopted the practice for two reasons — that they do not wish the rule to become common property, nor those who learn the rule to rely on writing and so neglect the cultivation of the memory. And, in fact, it does usually happen that the assistance of writing tends to relax the diligence of the student and the action of the memory. The cardinal doctrine they seek to teach is that souls do not die, but after death pass from one to another. And this belief, as the fear of death is thereby cast aside, they hold to be the greatest incentive to valour. Besides this, they have many discussions as touching the stars and their movement, the size of the universe and of the earth, the order of nature, the strength and the powers of the immortal gods, and hand down their lore to the young men.”

The few paragraphs above contain most of what history recorded about the Druids. As Caesar says, the Druids left no written records. After the conquest of Gaul, and during the Roman conquest of Britain, the last remaining Druids were hunted down and killed. One of the biggest slaughters was on Anglesey, a stronghold of the Druids in what is now Wales, in 60 A.D. Today, Celtic scholars base most of their work on archeology, which can sometimes reveal more about lost cultures that we might expect. Still, the Druids are likely to forever remain in the dark shadows of history.

My investigations of this period of antiquity, of course, is background research for the sequel to Fugue in Ursa Major. I would find it very wrongheaded to base a work of imagination on what others have imagined. Instead, I think it’s important dig out as much history as remains to be dug out.

Note: The translation from The Gallic War is by H.J. Edwards from the 1917 Harvard edition.