The New York Times reports on studies that have shown that going into the woods improves immune function. One Japanese study, for example, found that spending time in dense vegetation lowered cortisol levels, lowered the pulse rate, and lowered blood pressure. Another study found that two-hour walks in a forest over two days raised the number of white blood cells and caused natural killer cells to rise 50 percent.

Category: Health issues

Rehabilitating potatoes

I’ve written previously about how sweet potatoes have a lower glycemic index than white potatoes and are all around healthier than white potatoes. But lately I’ve become aware that there are things we can do to lower the glycemic insult of white potatoes.

If you Google around, you’ll find a number of sources that say that red potatoes are slightly less of a glycemic insult than white potatoes. But even better, when potatoes are cooked and then chilled in the refrigerator for 24 hours, the glycemic index goes down substantially. Boiled red potatoes, chilled and then eaten the next day, can have a glycemic reading as low as 56.

As I understand it, this is not simply because the potatoes are cold. It’s that, as the starch is chilled, the starch chemistry changes its structure so that it’s slower to digest. I believe this change persists even if the potatoes are reheated.

I keep seeing references to new types of low-glycemic potatoes developed by agricultural universities. But so far I have not been able to find a source of these potatoes, either as produce or as seed potatoes for planting.

Potassium broth

Now that I’m back on the cold and snowy East Coast, I’m remembering how good it is to have an arsenal of warm drinks. How about a bit of old-fashioned broth?

It was from Jethro Kloss, in the hippy handbook Back to Eden, that I first heard about potassium broth. Kloss’ version of potassium broth included oats and bran to give the broth extra body. He frequently prescribed it for people who were sick and couldn’t handle solid food. If you Google for “potassium broth,” you’ll find many versions. They all involve fresh vegetables, peels and all, simmered for four hours or so and strained.

The broth I made today included a beet, a turnip, a couple of potatoes, some celery, onions, turnip leave stems, collard stems, and the outer leaves from a cabbage. It’s still simmering, but I think I will add some tomato paste to the broth after I’ve strained out the vegetables, to make it taste more like vegetable soup.

It seems a waste to strain the broth and discard the vegetables, but I’ll drink the electrolytes, and my chickens will be happy to get the pulp.

Coffee substitutes

I’m amazed how easy it was to give up coffee. I decided that the caffeine couldn’t possibly be doing me any good. And besides, when one no longer has to go to work each morning, the caffeine kick really isn’t necessary. For years I was very San Francisco-ized in my taste in coffee. I drank it only in the morning, but I liked it rich and strong.

I’ve been using a brand of coffee substitute that I got at Whole Foods. It’s made from roasted barley with chicory. When you drink the first cup of it, you certainly know it isn’t coffee. But by the third cup, adaptation happens.

With coffee, color is everything. The color of the Roma coffee substitute, before cream and after, is the same as coffee. I am unable to achieve the proper color with soybean milk (it produces an awful gray color), so I’ve gone back to buying half and half, which gives that wonderful golden brown.

Another wonderful thing about being retired: There is no longer any temptation to eat and drink on the run, or at a desk, or in front of the TV. I always sit down at the table.

Has U.S. life expectancy peaked?

Life expectancy in the United States is at an all-time high. But like the stock market, it’s starting to look a little toppy. Life expectancy has started to decline in some parts of the United States, particularly rural areas and parts of the South.

According to LifeScience:

“Though the United States has by far the highest level of health care spending per capita in the world, we have one of the lowest life expectancies among developed nations — lower than Italy, Spain and Cuba and just a smidgeon ahead of Chile, Costa Rica and Slovenia, according to the United Nations. China does almost as well as we do. Japan tops the list at 83 years.”

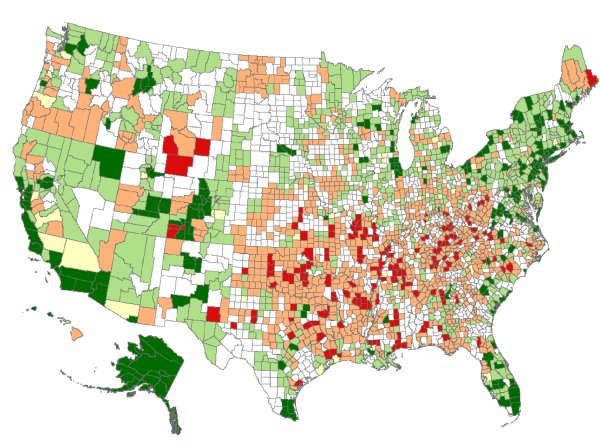

This online medical journal has charts showing how life expectancy is changing area by area. (It’s uncanny how a county-by-county chart of life expectancy looks like a voting-patterns chart.)

This is all very sad, because life expectancy would continue to rise if people took advantage of what we now know about diseases caused by diet and lifestyle.

Scrambled tofu

Vegetarians and vegans have known for a long time that one quick cure for a protein craving is scrambled tofu.

When I started buying tofu back in the 1970s, you could get it only at health food stores. Now even my country supermarket at Walnut Cove has it, organic. I always buy the firmest tofu I can get. Soft tofu has a slimy texture, and frankly I’m not sure what it’s good for. The tofu in the photo is scrambed with coconut oil, turmeric, Vegit seasoning, and a some fresh cayenne (the only thing in my garden that the deer haven’t destroyed). If you read up on turmeric, you’ll find that there seems to be something about it that keeps the aging brain young. Vegit is a general-purpose herb-and-yeast seasoning that is easy to find in Health Food Stores, or at Whole Foods.

Scrambled tofu goes good with chapati bread and Louisiana hot sauce. For dessert, I like a handful of raw walnuts, a spoonful of strawberry preserves, and a swig of soy milk. Combing amino acids from seeds (chapati bread), legumes (tofu and soy milk) and nuts makes for very high quality vegetable protein.

Rolling back the clock on sweets

These will be ready to eat tomorrow.

There are a couple of scenes in the BBC series Cranford, which is set in Cheshire around 1840, in which some children get very excited about the fact that their cherry tree has come into season. The children get a big thrill out of helping the new doctor in town knock cherries out of the tree. The BBC series, by the way, is based on the novel Cranford by Elizabeth Gaskell, a less well known but witty and competent 19th-century writer.

Children love sweets. In those days, cherries were high in the hierarchy of sweets, something for children to get excited about. These days, what child would pay the slightest attention to a cherry tree, or plain fresh cherries? Even though sugar was common in the 19th century, you could be sure that children in those days got a great deal less of it, especially provincial children. Sugar has, of course, gotten cheaper and cheaper, and the newest innovation in cheap sugar is high fructose corn syrup. Government corn subsidies help make it cheap, no matter how much evidence links high fructose corn syrup to Americans’ health problems.

But we don’t have to eat it. I can testify that if we stop eating processed sweets, we become more like the children in Cranford. A raw peach once again becomes a sweet treat. Watermelon is thrilling (the watermelons here have been inexpensive and very good this summer).

One of my grandmothers was a genius at making pies. I don’t think I can remember there ever not being at least one kind of pie in her pie safe. Usually it was a fruit pie, though she sometimes made custard pies. Still, nobody was fat, because it was home-cooked, and the dinner (which is what they called lunch) and supper tables were loaded with a variety of home-cooked foods including lots of vegetables. Once again, drawing on the insights of Michael Pollan, our grandmothers proved that a little homemade pie won’t hurt you.

You can get the Cranford series on DVD. I understand that the BBC has another season in the works to be shown in Britain this year around Christmastime. I’d expect it to be available in the U.S. next year.

Living to be 100

The Huffington Post has an article today on the growing number of people living to be 100 years old. One of the reasons cited for this is “improved diet.”

I think it would have been more accurate to say “the possibility of improved diet.” The diet of the average American has decidedly not improved. The July 20 issue of the New Yorker trumps the Time magazine piece on why Southerners are so fat with a piece on why Americans are so fat. The position of the New Yorker piece seems to be that the obesity epidemic of the past few decades has primarily been caused by corporate influences — food engineering, corporate agriculture, corporate research on food’s addictive qualities, pushing larger portions, marketing, etc.

We can take advantage of brilliant new research on diet and health, we can take advantage of the availability of healthier foods, and we can cook the right stuff for ourselves at home. Or we can eat what television commercials tell us to eat and make certain corporations richer. That’s what it really boils down to.

Chapati bread

The dough, kneaded and resting

Those of you who’ve been reading my scribblings here know that two tenets of my theory of cooking and health are that we should all eat like diabetics, even if we’re not; and that the elimination of simple carbs is the key to maintaining body weight.

The problem is, bread is probably my favorite food, and hot homemade bread is something I’d rather not imagine living without. So I’m always thinking about breads that are as easy as possible on the carbs and as low as possible on the glycemic index. That’s a short list of breads. But one such bread is whole-wheat chapati bread. It’s a dense, unraised flatbread. Google for recipes. I make it with King Arthur whole-wheat flour, water, and a bit of coconut oil. That’s right, not even any salt. For years I have noticed that unsalted bread can be much more interesting than bread with salt in it, with an eerily old-fashioned taste. I have no idea why. Anyway, like all wheat breads, the dough must be kneaded. Cook it well-floured on a dry griddle or pan.

Chapati bread goes exceptionally well with the curries of fresh summer vegetables that are my default supper this time of year.

Rolled and ready for griddling

Cook them hot so they blister and brown, but don’t let them smoke.

Chapati bread, curry of squash and peppers, and zingy peanut sauce

Dieticians give their blessing to vegans

A vegan summer supper here in the sticks. The tofu, walnuts, and sesame dipping sauce mix amino acids from legumes, seeds, and nuts to boost the quality of the protein. I’m not a strict vegan, but I eat lots of vegan meals. Tofu is mighty tasty if you dip it in the right stuff.

The American Dietetic Association released a position paper this month on vegetarian and vegan diets. You have to be a member of the association to read the full report, but the abstract is available on their web site:

“It is the position of the American Dietetic Association that appropriately planned vegetarian diets, including total vegetarian or vegan diets, are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide health benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases. Well-planned vegetarian diets are appropriate for individuals during all stages of the life cycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence, and for athletes. A vegetarian diet is defined as one that does not include meat (including fowl) or seafood, or products containing those foods. This article reviews the current data related to key nutrients for vegetarians including protein, n-3 fatty acids, iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, and vitamins D and B-12. A vegetarian diet can meet current recommendations for all of these nutrients. In some cases, supplements or fortified foods can provide useful amounts of important nutrients. An evidence-based review showed that vegetarian diets can be nutritionally adequate in pregnancy and result in positive maternal and infant health outcomes. The results of an evidence-based review showed that a vegetarian diet is associated with a lower risk of death from ischemic heart disease. Vegetarians also appear to have lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, lower blood pressure, and lower rates of hypertension and type 2 diabetes than nonvegetarians. Furthermore, vegetarians tend to have a lower body mass index and lower overall cancer rates. Features of a vegetarian diet that may reduce risk of chronic disease include lower intakes of saturated fat and cholesterol and higher intakes of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, soy products, fiber, and phytochemicals. The variability of dietary practices among vegetarians makes individual assessment of dietary adequacy essential. In addition to assessing dietary adequacy, food and nutrition professionals can also play key roles in educating vegetarians about sources of specific nutrients, food purchase and preparation, and dietary modifications to meet their needs.”