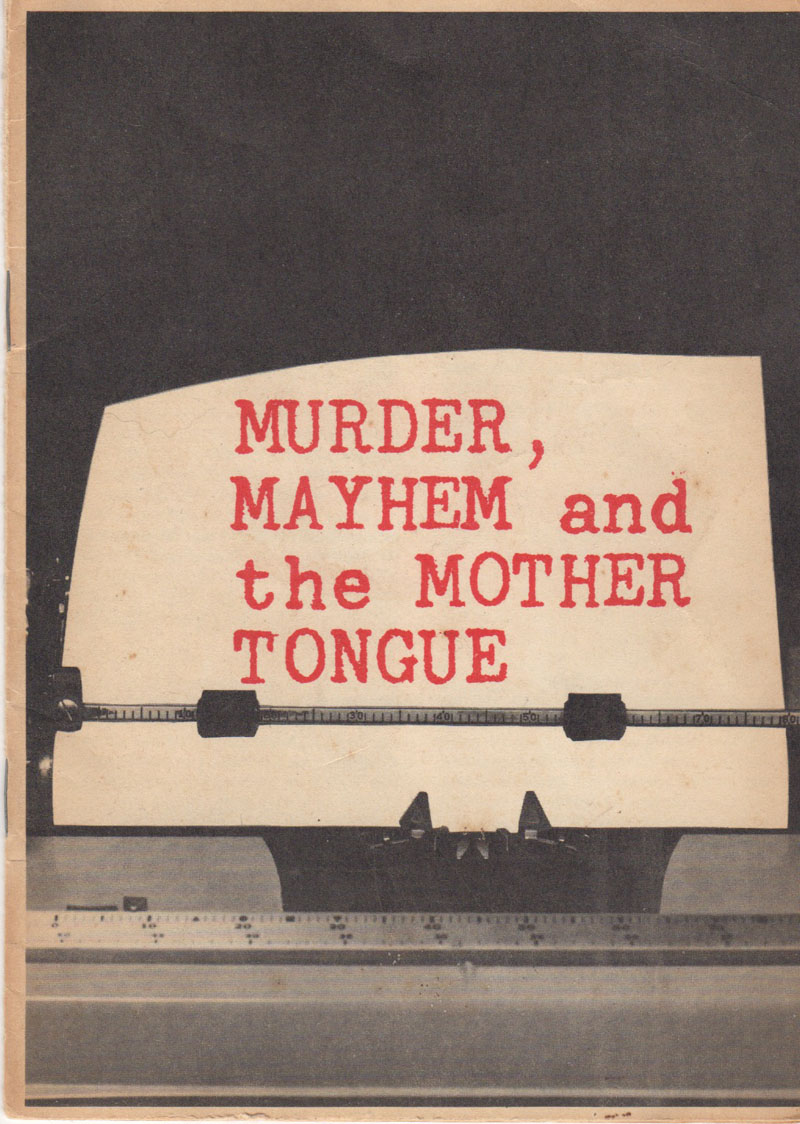

The cover of the rare 1969 pamphlet

Wallace Carroll’s “Murder, Mayhem and the Mother Tongue,” until now, existed only in the form of a pamphlet printed around 1969. A few are still in existence. At a reunion of former Winston-Salem Journal employees not too long ago, an old colleague gave me a copy if I promised to scan the text and get it on line. Here it is. Any errors in the text are mine. At last this piece is on the Internet so that it won’t be lost when the last pamphlet is lost.

Mr. Carroll was a journalist’s journalist. He was, without a doubt, the most important influence in my career, though I was just a young whipper-snapper when he was publisher of the Winston-Salem Journal. Here is a link to his obituary in the New York Times. He died in 2002 at age 95.

His staff idolized him, partly for his amazing background (see bio material below), and partly for his dignity, charisma, and kindness. He knew Churchill, and Eisenhower, and for that matter most of the American and European leadership during the World War II era. I will never forget how, when I was a copy boy, he would walk into the wire room, nod politely to acknowledge my presence, then stand in front of the Teletype machines reading, deep in thought. Later, as a young copy editor on his copy desk, my youthful sins against the language that got into print earned one or two of the brief, polite notes from the publisher’s office that made me crave to do better. Those of us who worked for him will never forget him. His book Persuade or Perish, which is still often cited by scholars, stimulated my longstanding interest in propaganda.

A future project, I hope, will be do to the same thing for “Vietnam — Quo Vadis.” That two-page editorial was very influential in getting the United States out of Vietnam. It is mentioned in the New York Times obituary. As far as I know, the only form in which that piece exists at present is in the clippings or microfilm files of the Winston-Salem Journal.

Murder, Mayhem and the Mother Tongue

An address given by Wallace Carroll, then editor and publisher of the Winston-Salem (N.C.) Journal and Sentinel, on receiving the By-Line Award of Marquette University at Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on Sunday, May 4, 1969.

I rise to speak of murder. “Murder most foul, strange and unnatural,” as Hamlet called it. Or, to use the more precise words of Professor Henry Higgins, “the cold-blooded murder of the English tongue.”

This cold-blooded murder is committed with impunity day in and day out, and each one of us is at least an accomplice. The language of our fathers is mauled in the public schools, butchered in the universities, mangled on Madison Avenue, flayed in the musty halls of the bureaucracy and tortured without mercy on a thousand copy desks.

Because of our brutality and neglect, the English that is our heritage from Shakespeare, from Addison and Steele, from Shelley and Keats, from Dickens and Thackeray, from Conrad and Kipling — this English is now on its way to the limbo of dead languages. Certainly, the language has changed more in the past ten years than in the previous one hundred — and the change has been entirely for the worse. And, if nothing is done to check this deadly process, our children and their children will speak in place of English a deadly jargon, a pseudo-language, that might best be called Pseudish.

This is a prospect that should alarm everyone who earns his living by the spoken or written word. Leaving pictures aside, the only thing we have to offer our readers and listeners is words — words arranged in more or less pleasing patterns. But as things now go, those patterns are becoming less and less pleasing — to the eye and to the ear. Even if we look upon spoken and written news as a mere article of commerce, the trend is an ominous one.

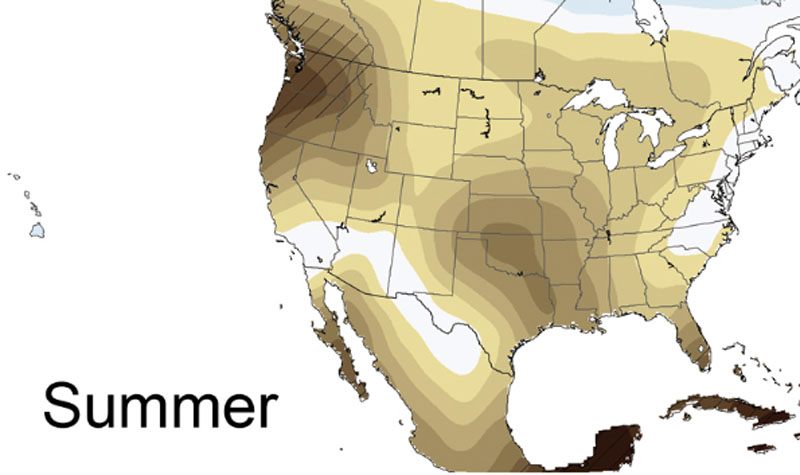

But the debasement of English as we have known it should also concern everyone outside our journalistic circle. For the English language — as I hope to prove to you — is one of our great natural resources. It is as much a natural resource as the air we breathe, the water we drink and the timber and minerals that have made possible our material growth. Yet we are now polluting this priceless resource as senselessly as we have polluted the air and lakes and streams, and we are despoiling it as ruthlessly as we have despoiled our forests and mineral wealth.

The consequences for the American people could be as grave as the consequences we now have to face because of our heedless exploitation of our other natural resources.

The assault on the language begins in the public schools. We all know how Abraham Lincoln learned to read, lying on the floor of a log cabin, a candle or oil lamp at his elbow, puzzling out the words in an old Bible or whatever book he could lay hands on. Now, if Abraham Lincoln had enjoyed the advantages of our present-day schooling, he would never have discovered the strength and beauty of the language in this way. For Abe would have learned, not to read, but to “acquire a reading skill.” There is something about this curious term that suggests what a plumber’s apprentice goes through in acquiring a plumbing skill. In any event, the teacher, who had already been convinced by her courses in education that reading is a hard, tedious, mechanical process, would have conveyed the same feeling to the boy. And so Abraham Lincoln might have become an adequate plumber, but he certainly would not have written the Gettysburg Address.

Still, having acquired a reading skill, the boy might have advanced to something even more grand — a course in “language arts.” If you will compare the plain, clear word “English” with this pretentious and really meaningless term, “language arts,” you will see what I am getting at. Or perhaps you will grasp it more easily if I quote a few words from Winston Churchill, a man who never took a course in language arts, though he did learn something about English:

“By being so long in the lowest form (at Harrow), I gained an immense advantage over the cleverer boys. I got into my bones the essential structure of the ordinary British sentence — which is a noble thing. Naturally I am biased in favor of boys learning English. I would make them all learn English: and then I would let the clever ones learn Latin as an honor, and Greek as a treat.”

It is a good thing for you and me that Churchill learned English and not language arts. For if he hadn’t learned English (and I will explain this further), his England would have perished three decades ago. And then our America would have been left alone in a world of pernicious ideologies and relentless dictators.

I put this stress on “reading skills” and “language arts” because they are the most obvious symptom of linguistic blight that someone has called “Educanto.” A teacher who has mastered Educanto can rattle off such expressions as “life-oriented curriculum,” “learner-centered merged curriculum,” “empirically validated learning package” and”multi-media and multi-mode curricula.”

And such a teacher can easily assure you that “underachievers and students who have suffered environmental deprivation can be helped learning-wise by differentiated staffing and elaborated modes of visualization.”

Of course, this passion for pompous and opaque expression is only the merest beginning. The higher we go in the educational maze, the more overblown does the lingo become. Our universities have in fact become jargon factories: the more illustrious the university the more spectacular its output of jargon. And let someone find an awkward, inflated way to say a simple thing and the whole academic pack will take it up. I once remarked to a group of distinguished scholars that they would be offended if someone offered them the second-hand clothes of a Harvard professor, but they seemed only too proud to dress their thoughts in the man’s second-hand gibberish.

Speaking of Harvard, we were told a few days ago by the faculty that the old place is about to be “re-structured.” That word, if it really is a word, conveys to me a picture of what Attila did to Europe, and perhaps Harvard deserves as much. Certainly something is due an institution that turns out scholars who speak like this:

“You must have the means to develop coherent concepts that are sufficient to build up a conceptual structure which will be adequate to the experiential facts you want to describe, and which will not only allow you to characterize but also to manipulate possible relationships you had not previously seen.”

In a spirit of mercy I shall skip what is done to the language Madison Avenue-wise and business-wise, and proceed directly to the apex of government in Washington.

Here we discover that the President doesn’t make a choice or decision: he exercises his options. He doesn’t send a message to the Russians: he initiates a dialogue — hopefully (and what did we ever do before the haphazard “hopefully” came along?) a meaningful dialogue. He doesn’t try to provide a defense against a knockout blow: he seeks to deny the enemy a first-strike capability. He doesn’t simply try something new: he introduces innovative techniques.

All this and more he does after in-depth analysis has quantified the available data as input so it can be conceptualized and finalized for implementation, hopefully in a relevant and meaningful way.

Of all people, those of us who write and edit the news should be the guardians at the gate, the protectors of the public against this kind of barbarism. But what do we do? We not only pass along to the reader the Educanto, the gobbledegook and the federalese, we even add some nifty little touches of our own.

Thus the resourceful reporter is likely to uncover meaningful decisions and meaningful dialogues all over the landscape. Or rather at all levels — the national level, the state level, the community level, the frog-pond level. And in every community — the scientific community, the academic community, the black community, the business community, the dog-catching community.

Then the editorial writers do their bit. These meaningful dialogues, they assure us, are adding new dimensions to our pluralistic society. And where this same society is going to stack all those new dimensions is something that will really call for some innovative techniques.

Then we get the syndicated columnist who writes like this: “The key element in this mix of Nixon amelioratives and public concerns is that ephemeral element of confidence in the President and his conduct of the office. If Richard Nixon were in trouble on the personal confidence dimension, he could well be on the brink of imminent slippage.”

Now add to all this human ingenuity what the machine has done to the language. The Morkrum printer that brings the wire reports into the newspaper office chugs along at a 66 words a minute. The linecasting machine in the composing rooms sets type at a rate of eight to twelve lines a minute. The machine is mightier than the mind, and news writing must sacrifice all grace and clarity to accommodate these physical limitations. Thus most definite and indefinite articles must be eliminated in news writing. So must prepositions and constructions that require commas. Identification must be crammed together in front of a man’s name so that everyone gets an awkward bogus title. All the flexibility and lilt must be squeezed out of the writing so it reads as if the machine itself had composed whatever is written.

And we get leads like this:

“Teamsters union president James R. Hoffa’s jury-tampering conviction apparently won’t topple him from office under a federal law barring union posts to anyone convicted of bribery.”

Clickety-clickety-click. It’s not English — it’s Morkrumbo, the language of the Morkrum printer.

“ ‘Daddy,’ shrieked champion space walker Eugene A. Cernan’s daughter, Teresa, 3, as she raced to her father.”

And…

“Former North Carolina State University’s head basketball coach Everett Case today declared …” Clickety-clickety-click.

Of course, our lucky colleagues in radio and television are free from the tyranny of the Morkrum printer and the linecasting machine. And they have had fifty years to develop an easy conversational style. So they, at least, have managed to preserve a little of the grace of pre-Morkrumbo English…. Or have they? Listen to one of the great men of television:

“Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy today declared … Housing and Urban Development Secretary George Romney today told newsmen … “

You can almost hear the clickety-clickety-click of the Morkrum printer in counterpoint to the broadcaster’s voice. The language of news broadcasting is frequently the purest Morkrumbo — a language devised for the convenience of the machine, not for the pleasure of the human ear.

But why should anyone care? Well, as I said earlier, the English language as it came to us from our fathers has been one of our great natural resources. And that is what I must now prove.

At least twice during my lifetime I have seen the English-speaking nations raised from despair and defeat almost by the power of the language alone.

The first time was during the Great Depression. It is hard to realize today how low our people had fallen. America had been eternally blessed. Americans had gone ever forward and the future held nothing for them but more and more wealth and happiness. Then came the great crash. The farmer was driven from his farm. The worker was sent home from the factory. Fathers scrounged in garbage cans, mothers prostituted themselves to feed their children. Was this the end of the system? Was this the end of the American dream?

Then the American people heard on the radio the voice — the unforgettable voice — of Franklin Roosevelt:

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

He had no program when he said it. His concept of economics was as silly as Herbert Hoover’s. But he told the people: “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” And the panic began to subside and the people began to hope again.

Go back to the history of those days and read the words of Roosevelt. Easy English words. Simple declarative English sentences.

Then go back to the year 1940 and the story of the Battle of Britain. Hitler’s invincible armies, his equally invincible air force, were poised at the Channel. Britain, its little army driven from the Continent and unprepared for total war, stood alone. Then the British people heard the voice of Winston Churchill:

“I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.”

Blood, toil, tears and sweat — four bleak one-syllable, Old English words. Only a great leader would have dared to make such a promise — and the British people suddenly knew they had such a leader.

“We shall fight on the beaches (he said), we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills, we shall never surrender.”

How simple the words — nothing but crisp, clear declarative statements. But they stirred in every man and woman in the land the urge to be a hero.

Legend has it that Churchill then put his hand over the microphone and said as an aside: “We shall hit them with beer bottles; because — God knows — that’s all we’ve got.”

It was certainly in character and almost literally true. I remember a trip I made at the time to the Channel coast to see whether the British were really capable of repelling an invasion. I remember meeting an unknown general named Montgomery, who had been driven out of Belgium and northern France, and whose shame and resentment burned in every word and gesture. The best he could show me was a platoon of infantry — 16 men — armed with tommy-guns from America. When I returned to London I did a little checking and learned that those were the only 16 tommy-guns in the British Isles. Yet Churchill said:

“We will fight on the beaches … we will never surrender.”

And the people believed him.

Then he turned to America and said:

“Give us the tools and we will finish the job.”

Note that he did not say: “Supply us with the necessary inputs of relevant equipment and we will implement the program and accomplish its objectives.”

No, he said: “Give us the tools, and we will finish the job.”

And across the Atlantic, Roosevelt heard him and spoke this simple analogy to the American people:

“Suppose my neighbor’s home catches fire, and I have a length of garden hose four or five hundred feet away. If he can take my garden hose and connect it up with his hydrant, I may help him put out his fire. Now, what do. I do? I don’t say to him before that operation, “Neighbor, my garden hose cost me $15, you have to pay me $15 for it. I don’t want $15 — I want my garden hose back after the fire is over …”

With plain backyard talk like this, Lend-Lease was born, Britain was saved and America gained time to arm for war.

My friends, the English language has stood us in good stead. And never doubt for a moment that we shall need it again in all its power and nobility. That language, as it was entrusted to us by our fathers, enables us to stand with Henry V at Agincourt, with Thomas Jefferson at the birth of this Republic, with Lincoln on the hallowed ground of Gettysburg, with Roosevelt at the turning point of the Great Depression, with Churchill in Britain’s finest hour.

That language gives every man jack of us a right to claim kinship with Will Shakespeare of Stratford, with Wordsworth of the Lake country, with Thoreau of Walden Pond, with Bobby Burns of Scotland, with Yeats and Synge and O’Casey of Ireland and with all the others from whom a great people can draw its character and inspiration.

Let us not allow the latter day barbarians to rob us of this birthright. Rather, taking our watchword from Winston Churchill, let us resolve today:

We shall fight them in the school rooms, we shall fight them on the campuses, we shall fight them in the clammy corridors of the bureaucracy, we shall fight them at their mikes and at their typewriters. And when we win — as win we shall — we shall bury them in the rubble of their own jargon. Because, Lord knows, they deserve nothing better.

About the Author

When this was written in 1969, Wallace Carroll was the editor and publisher of the Winston-Salem (N.C.) Journal and Sentinel. Before that he was news editor of The New York Times Washington Bureau. He was well known as both a writer and editor.

A native of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, he was graduated from Marquette University in 1928 and immediately went to work for the United Press in Chicago. A year later he was sent to London, in 1931 to Paris, and in 1934 to Geneva, where he was manager of the UP bureau at the League of Nations. In 1938 he covered the Spanish Civil War, then moved to London as bureau manager. He directed UP operations in Europe during the London Blitz and the first two years of World War II.

When the Nazis struck Russia in 1941 he was on the first British convoy that carried aid to the Russians. He covered the defense of Moscow — and won a National Headliners Club award for it. Returning to the United States, he was the first newspaper reporter to tour Pearl Harbor after the attack.

In 1942 he became director of the U. S. Office of War Information in London and advisor on psychological warfare to General Eisenhower. Two years later he moved to Washington as deputy director of OWI’s overseas branch.

After the war he became executive news editor of the Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel. He joined The New York Times in 1955 and managed its Washington bureau for eight years. In 1963 he returned to Winston-Salem as editor and publisher.

He was the author of Persuade or Perish, an account of U. S. psychological warfare operations in Europe, and of many magazine articles. He has lectured at the National War College, the Air War University, and the Foreign Service Institute and served as a consultant to the State and Defense departments, the Ford Foundation, and several universities. He held an honorary LL.D. degree from Duke University.

Mr. Carroll died in 2002. Here is a link to his obituary in the New York Times.